Autobiography (detail), Huai Su, Tang Dynasty. Handscroll, ink on paper, 28.3 x 755 cm. Courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei City, Taiwan

For 25 years the Getty Research Institute has been inviting scholars from around the world to visit, do research, and ask provocative questions. During his recent stay, Zhu Qingsheng (LaoZhu), director of the Center of Visual Studies at Peking University, asked this: when Westerners and Easterners talk about art, are we talking about the same thing?

In Europe and the U.S., we’re used to art that’s deeply rooted in society, politics, economics, and beliefs. Since the early 1900s, this conception of art has prevailed in China as well. But for nearly two millennia before—since the dawn of a self-aware Chinese art around A.D. 200—worldly concerns were antithetical to the Chinese understanding of art.

To understand traditional Chinese art, LaoZhu says, we need look at its defining form: shufa, or writing art. Shufa is what we call calligraphy, from the Greek for “beautiful writing.” But the term isn’t quite right. “Chinese calligraphy isn’t about beauty,” LaoZhu points out. “Sometimes it’s angry.”

The closest parallel to shufa in Western art is the madly expressive marks of Cy Twombly, not the carefully trained letterforms of illuminated manuscripts. And the “crazy cursive” of 17th-century artist Wang Yuanqi finds its closest match not in the European Baroque of the same period, but in the expressive brushstrokes of Van Gogh.

Centuries before the dawn of modernism in Europe, Chinese calligraphers were creating art for art’s sake.

In its highest form, shufa also offered something more: a way to transcend history and connect with the eternal through creativity. “The best time for shufa,” said one master, “is when drunk. You wake up and don’t realize the writing is by you.” What makes a piece great in Chinese art is therefore not its content, LaoZhu explained, but “its ability to prompt viewers to engage with the artist and sense his moment of existence while writing.”

If traditional Chinese art is about freedom from the limits of history and time, can we ever write a true history of Chinese art? For LaoZhu, asking this question provides an opening. Perhaps now, as China and the West grow ever closer, we can transform art history from a field tied to Western art into one that could describe a truly human history and culture. One where Wang Yuanqi and Vincent van Gogh can begin to talk to one another.

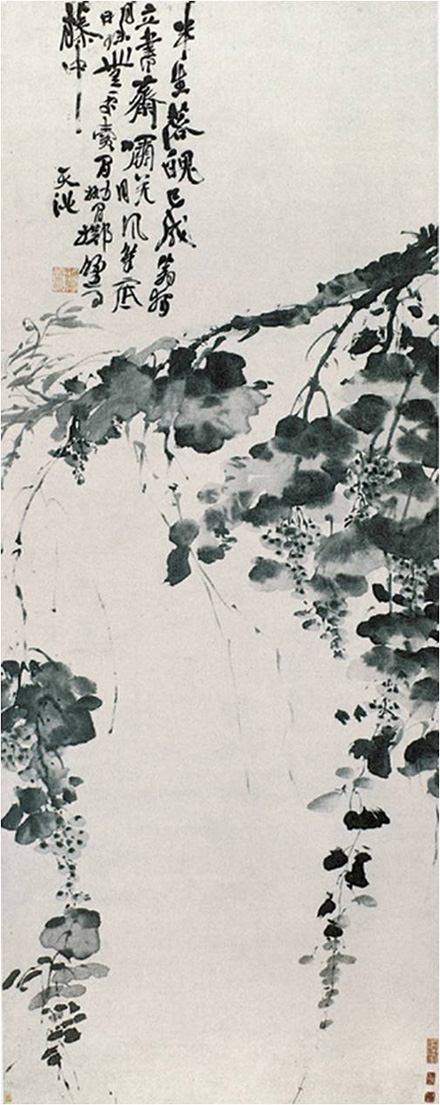

Grapes, Xu Wei, Ming Dynasty. Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 165.4 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing, China

Annelisa – I love the poetry of this entry…perfectly suited to the topic at hand. The comparison to Cy Twombly makes so much sense, especially considering his studies under abstract expressionist and Zen enthusiast Franz Kline. Van Gogh, too, was deeply passionate about Zen Buddhism–see his “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (Bonze)”. A “Bonze” is the Japanese term for a monk, and van Gogh wrote of this painting that he specifically shaved his head to look more Buddhist. ~jennifer

http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/vangogh/slideshow/slide_work11.html – link to the painting I spoke of above.

A New look at Chinese Art — posted on March 23, 2011.

Are you sure the Chinese paining “Grapes,” by Xu Wei, is actually a painting of grapes?

The Chinese character on top left is Wisteria. Can this be a painting of wisteria flowers? There look like they are.

Hi Michael — That’s a very interesting question, and you have a very perceptive eye! I asked my colleague Julia Grimes of the Getty Research Institute and she agrees that she sees part of the character for wisteria, 紫藤 (ziteng), in the first line. The characters at the top left constitute a poem that reads as follows, according to “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” (Yale University Press, 1997): “Half my life wasted, now an oldster am I; / Alone I stand in the study as the night wind howls. / Pearls from my pen can find no buyer; / Then let them scatter amidst the vines.” That last line might more accurately read, incorporating your observation, as “…amidst the wisteria vines.” Most English-language sources agree in giving the title of the painting as “Grapes.” However, artists typically didn’t give their paintings titles, and sometimes paintings have acquired titles in English that are different from those they have in Chinese. As different characters can have multiple readings, too, the whole issue of titles is indeed quite complex.

Brilliant article. Looking at personal calligraphy in a language one doesn’t know heightens the effect. Try this: play a movie in a foreign language. Don’t look at it. Just listen to the soundtrack for an hour or so. A whole new untranslatable world that nevertheless has thousands of shifting meanings…