The real Beth: curator of manuscripts Elizabeth Morrison

When you write novels for a living, as I do, you get used to making things up—places, plots, people.

What you don’t expect is to hear back from one of those characters you’ve cooked up out of thin air. Imagine the nerve!

But that’s exactly what happened to me when I wrote a novel called Bestiary, the heroine of which was a curator of medieval manuscripts at the Getty. A character I named Beth Cox.

Shortly after the book was published, I got the strangest e-mail, from a woman wondering if we had ever met. It seems her name, too, was Beth…and she worked as a curator of medieval manuscripts…at the Getty. She’d picked up the book from an airport rack because, well, bestiaries were her particular specialty…just as they were my heroine’s.

Furthermore, while her last name wasn’t Cox—it was Morrison—she had indeed dated a guy named Cox (“whom my mother was dying for me to marry”). And after checking my website, she also discovered that she had been born in Princeton, New Jersey, where I’d gone to college, while she had gone to Northwestern in Evanston, Illinois, the town where I was born and raised. The coincidences went on from there, and as the real Beth put it in that e-mail, “I was quite pleasantly surprised to find that the basic material of my life could be intriguing enough for an author to invent it!”

Well, as you can guess, we had to meet in person, which we did, over lunch in the Getty cafeteria. Again, I saw that I had most of the details right—she was young, pretty, tall, but, disappointingly, a redhead. My Beth was a brunette. How could I have been so wrong?

After lunch—where I had to swear up and down that I had never met, seen, or heard of her before writing the book—the real Beth (or so she continued to contend) took me on a private tour of the medieval galleries, where I had been a frequent visitor on my own while doing my research. I was also treated to a preview of her show, Medieval Beasts, revolving around, of course, the three gorgeous bestiaries in the Getty’s own collection.

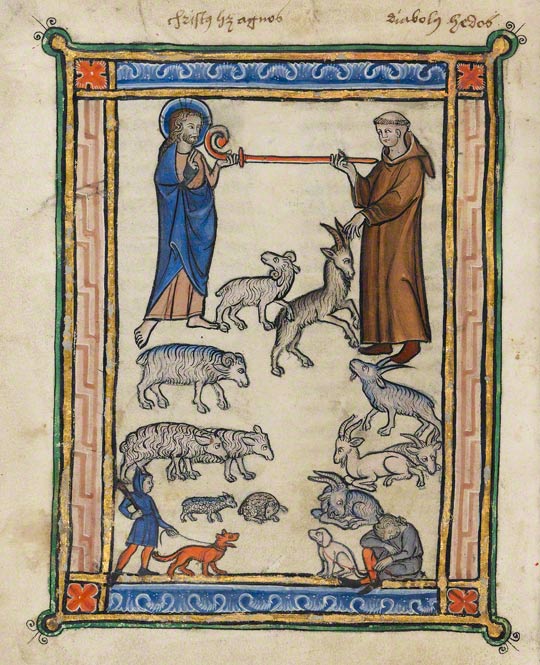

Christ and a Monk and Two Shepherds in a Franco-Flemish bestiary made about 1270, on view in the exhibition Illuminated Manuscripts from Belgium and the Netherlands through February 6

Still, I don’t want to give the impression that it was all smooth sailing. Beth took issue with two elements in the book. First, I had written that the heroine and her hubby lived in a lavish, multi-million-dollar home rented to them for a pittance by a museum trustee. “That would never happen,” she confided. “The Getty has strict rules about stuff like that.” I had also written that she used a nifty computer program to translate ancient Latin into English, at the push of a button. “No such thing exists, but if it ever does, I can guarantee you that I’ll be the first in line!

Today, we are friends—all three of us. The fictional Beth is off living her life in some story I have yet to concoct, while the real Beth and I meet for an occasional lunch, or at one of the exhibitions she curates, like the current, spectacular Imagining the Past in France, 1250–1500.

My upcoming novel, The Medusa Amulet, is, again, art-related. It’s a supernatural thriller based on the life of 16th-century sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, whose bronze statue of a satyr is part of the Getty’s permanent collection.

Although I’m not expecting to get an e-mail from Cellini this time around, I have learned to keep an open mind. And if you still don’t believe that life imitates art, just ask Beth. Either one.

Text of this post © Robert Masello. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks