Allan Sekula was an artist and theorist ahead of his time. When globalization was still a little-understood phenomenon, he recognized the enormity of its changes—from maritime transformations to labor conditions—and brought them to light in socially and critically engaged work.

The Getty Research Institute has just acquired Sekula’s papers, which document the career of the artist, writer, and teacher. Housed in over four hundred boxes, the contents include his writings, notebooks, correspondence, research materials, transparencies, photographs, posters, and many other visual and audio items.

In his artmaking and his writings, Sekula emphasized the importance of the archive to photography, so it is fitting that he left behind such a meticulous, well-documented monument to his own process. Once catalogued and made available for study, the extensive trove of material will enable scholars and researchers to piece together the behind-the-scenes development of Sekula’s practice.

From Marine Biologist to Artist

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1951, Sekula developed an interest in the ocean as a boy when his family moved to San Pedro, California. He pursued marine biology, earning a BA in biology at UC San Diego, but after taking courses with artists John Baldessari and Herbert Marcuse, he changed focus, earning an MFA there in 1974.

In addition to his artistic practice, Sekula is widely known for his writing; he is considered one of the most influential 20th-century theorists and critics on photography. Sekula first earned attention as a writer while still in school, when his MFA thesis, “The Production of Photographic Meaning,” was published in Artforum magazine. This was followed in 1984 with a now-classic anthology, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973–1983. Sekula saved all his drafts, and handwritten and typewritten essays in the archive contain his annotations, deletions, and revisions.

Sekula’s impact can also be felt through his extensive work as a teacher. Over the course of his career, he taught in the photography, cinema, and media departments at New York University, Ohio State University, and above all, CalArts, where he was a professor from 1985 until his death in 2012. Syllabi, course readers, pedagogical materials, and other documents related to his teaching are well-represented in the papers.

A Socially Engaged Eye

Sekula’s hallmark as an artist was the photographic series, frequently intercut with textual or discursive elements, and always political. His breakthrough occurred in 1972, while he was still a student, with Untitled (Slide Sequence), a series of covert photographs of workers leaving an aerospace factory in San Diego. Sekula’s father worked in the aerospace industry, and the artist’s next project, Aerospace Folktales (1973), documented his parents’ day-to-day life in their small apartment following his father’s layoff.

In addition to 51 photographs and texts set in frames, Aerospace Folktales was originally exhibited alongside three audio tracks—interviews with both parents and Sekula’s own commentary—and three director’s chairs and potted plants. The combination of audiovisual materials and props in one installation became another trademark of his work.

Sekula’s best-known project is Fish Story (1989–95), which combined his interests in the maritime industry, labor, and globalization. Traveling with cargo ships to port cities around the world, including Hong Kong, Rotterdam, New York, and more, he designed the arrangement of over 100 photographs with 26 texts for presentation in both exhibitions and as a book.

Panorama. Mid-Atlantic, November 1993, 1993, from Fish Story, 1989–95, Allan Sekula. Photograph. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.22. © Allan Sekula Studio LLC. A partial gift from Sally Stein, in memory of her husband Allan Sekula

LA Uprising #14, April 1992, 1992, from Fish Story, 1989–95, Allan Sekula. Photograph. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.22. © Allan Sekula Studio LLC. A partial gift from Sally Stein, in memory of her husband Allan Sekula

While many twentieth-century photographers stressed the instantaneous nature of the medium, Sekula worked in series over prolonged periods of time, crafting meaning from an entire body of images rather than a single shot. He often modified the selection and sequence of photographs in his exhibitions and publications, along with other facets. For example, the artist removed his own recording from Aerospace Folktales after its initial presentation, reducing the number of soundtracks from three to two.

Sekula’s photographic work is scrupulously archived in the papers, with over 156,000 exposures in 450 binders and 2,200 non-editioned prints. All of the transparencies are catalogued chronologically and by project, providing the most complete set of the artist’s output for each of his series. Audiovisual materials related to his film and video work, installations, and lectures—including cassette tapes and DVDs—are also part of the collection.

Military air show and Gulf War victory celebration, El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, Santa Ana, California, 28 April 1991, from War Without Bodies, 1991/1996, Allan Sekula. Photograph. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.22. © Allan Sekula Studio LLC. A partial gift from Sally Stein, in memory of her husband Allan Sekula

Behind-the-Scenes Insights

Sekula rigorously documented his artistic progression, making his archive a valuable tool to trace his evolving thought process.

His papers contain 143 notebooks dating from 1970 to 2012, written in clear handwriting and incorporating over 1,470 pages of illustrations. Sekula wrote about most of his major artworks in these books, tracking their conceptualization and the process of bringing them to fruition. He noted every change made over the course of a project’s development, producing a highly detailed portrait of its genesis.

In addition to recording his creative evolution, Sekula wrote about his personal and professional life, conveying his thoughts about places he was traveling, books he was reading, and things he was seeing. In keeping with his socially minded art, he was a keen observer of the effects of globalization, commenting on the changes he witnessed to people’s social and economic realities.

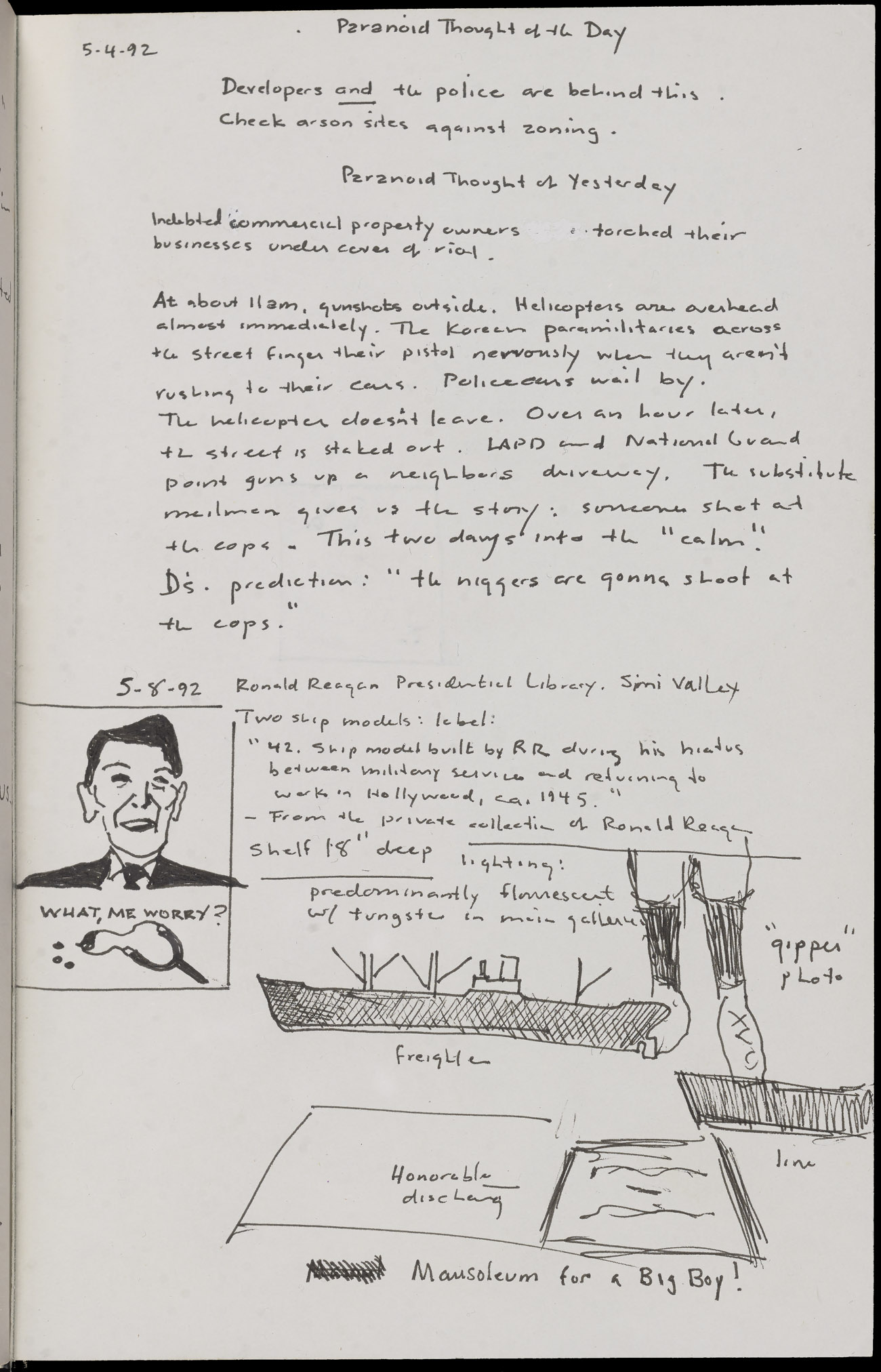

One notebook entry from May 4, 1992, the sixth day of the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, features a “Paranoid Thought of the Day”: “Developers and the police are behind this. Check arson sites against zoning.” The “Paranoid Thought of Yesterday” reads: “Indebted commercial property owners torched their business under the cover of riot.” He added a description of hearing gunshots, helicopters, and police outside at 11:00 in the morning, noting how it occurred two days into what was supposed to be “the calm.”

May 8, 1992, records a visit to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley. The words “Mausoleum for a Big Boy!” underscore both text and sketches, including a “ship model built by RR during his hiatus between military service and returning to work in Hollywood, ca. 1945” and a drawing of the former president alongside a slingshot and the phrase “What, me worry?” Almost a decade earlier, Sekula had created Sketch for a Geography Lesson.

Notebook, 1992, Allan Sekula. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.22. © Allan Sekula Studio LLC. A partial gift from Sally Stein, in memory of her husband Allan Sekula

SoCal Connections

Sekula conversed with many prominent art-world figures, and his correspondence includes letters from critics Benjamin Buchloch, Rosalind Krauss, Susan Sontag, and more. He was a supporter and advocate of his artist friends and students, and his archive also features materials pertaining to Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, Yolanda Lopez, Fred Lonidier, and others.

In addition to letters, Sekula held on to documents behind the planning of his exhibitions, and numerous drawings and diagrams reveal the care with which he thought out the display of his pieces. The papers also contain various collections amassed over the course of his research for different projects, including postcards, newspaper clippings, and political propaganda, often from Los Angeles or Southern California and pertaining to subjects such as the shipping industry and the history of San Pedro.

Based in Southern California for most of his life, Sekula had an ongoing relationship to the Getty. He was a Getty scholar in 1996–97, he exhibited at the Getty Research Institute, and his photographs are in both the Getty’s institutional archives and the J. Paul Getty Museum’s holdings of photographs.

It is therefore fortuitous that his archive will, once catalogued, be available to researchers visiting the Research Institute’s special collections. Sekula’s papers provide a rich, detailed portrait of an artist and thinker whose socially committed practice reflected and influenced not just the region, but the world at large.

See all posts in this series »

Hello, I am a professor at USC and would like to use some of Allan Sekula’s materials for a book that I am publishing. Can you tell me if this archive is accessible? Thank you.

Hi Juan, Thanks for writing in. The Sekula archive is not yet accessible to researchers because it is being processed and catalogued. You can check our Allan Sekula Archive webpage for updates. If you are interested in the subset of images that have been digitized, you can contact the Getty Research Institute rights and reproductions folks (see email form linked from the right sidebar of the same page). Thanks for your interest! —Annelisa / Iris editor