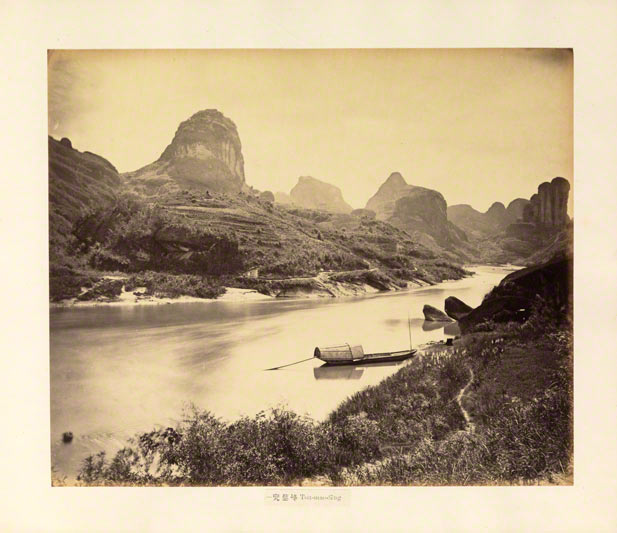

Plate from Album of Bohea or Wu-e Photographic Views, 1860s–70s, Tung Hing (Chinese, active 1860s–80s), albumen silver prints. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.R.23.39

The new exhibition Brush & Shutter: Early Photography in China uses photographs, along with a few paintings and other artistic media, to tell a largely unknown story about China.

In the second half of the 19th century, when China was politically weak, several enterprising Chinese artists and reformers embraced the new technology of photography that arrived with the foreign “barbarians.” Innovative artists who were painting—with brushes—portraits or landscapes for export began using camera shutters to capture images. In so doing, they became photographers.

Portrait of Li Hongzhang in Tianjin, 1878, Liang Shitai (also known as See Tay) (Chinese, active in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Tianjin, 1870s–1880s), albumen silver print. The Getty Research Institute, 2006.R.1.4

Some Chinese shutter experts, such as the Tung Hing studio, featured views of dramatic rock faces and river scenes in Fujian province, artistic themes that for centuries have been the hallmark of Chinese “mountain-water” ink paintings, but here these views are encased in a photographic album. Other Chinese photographers, such as Liang Shitai, specialized in portraits of high-ranking officials, but these images were then embellished with either hand-brushed Chinese characters or hand-stamped name chops.

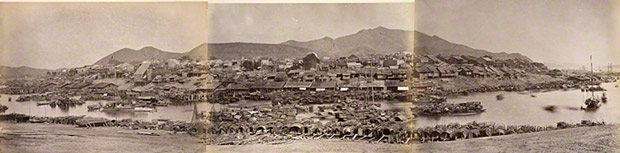

Several Chinese photographers, Lai Afong among them, assembled multiple-image panoramas of Chinese cities, some of which were just being “opened up” to foreign commerce and, thus, they began to show the architectural footprints of the European traders: factories, churches, mansions, and offices.

General View of Wuzhou, 1860s, Lai Afong (Chinese, 1839–1890), albumen silver print. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.R.22.37

The surprising story that Brush & Shutter tells, in one gorgeous gallery and in one captivating catalogue, is a thrilling one that resonates with China’s powerful rise on the world stage today. Chinese entrepreneurs are again adapting foreign technologies, from high-speed trains to iPads. Chinese artists are again demonstrating distinctive visions of contemporary life, as can be seen in the exhibit Photography from the New China.

For all the tantalizing images that Brush & Shutter contains, however, it only begins to tell a story—one whose fuller dimensions will only be understood after more work by early Chinese photographers comes to light. This exhibition, then, is a first step on a longer journey.

For those who want to take further steps (without venturing to China), you may enjoy the catalogue, co-edited with my fellow curator Frances Terpak, in which several scholars probe even more deeply into this rich vein of photographic material.

Having seen The Forbidden City Collection in Salem, MA, PEM & the Met in NYC, I am anxious to visit with the next medium of expression in China. Congratulations on the occasion of this event. PHD.MD. Boston, MA