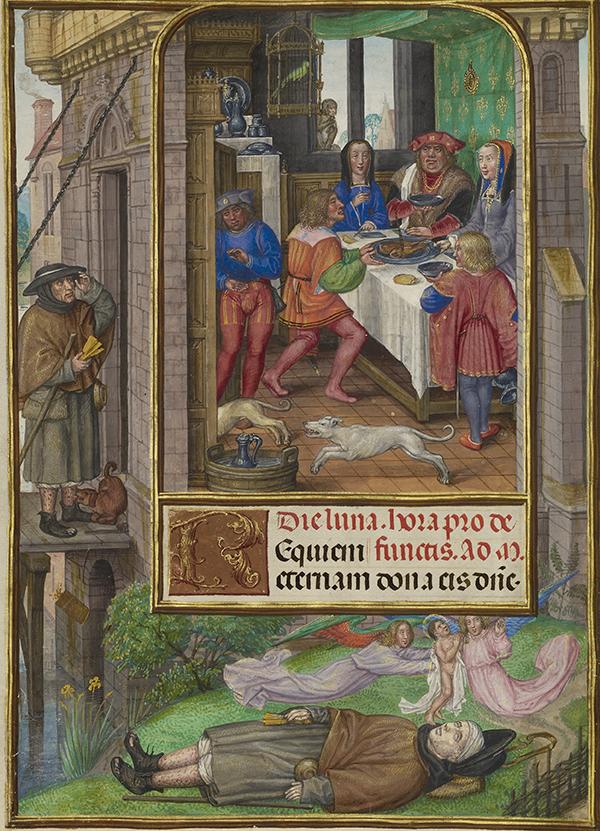

The Feast of Dives, about 1510–20, Master of James IV of Scotland. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 9 1/8 x 6 9/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fol. 21v

Images of banquets and festivals from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern era depict rooms packed with huge crowds. But people aren’t the only ones enjoying the party. Look carefully and you’ll see some familiar figures: dogs!

In fact, canines are surprisingly ubiquitous in historical images of feasting. Why?

Nobility’s Best Friend

Portrait of Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone at Seven Years of Age, 1755–56, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Pastel on vellum, 21 5/8 x 17 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.PC.273

Dogs were a symbol of nobility and wealth. For example, the French royal family is known to have gifted dogs to its princes to raise and keep as company, while noble women raised small dogs as pets, often lapdogs or toy dogs.

Dogs such as alaunts, greyhounds, mastiffs, and spaniels were particularly valued because of their association with hunting, a noble activity. These hunting breeds were expensive to purchase as well as to maintain, an extravagance that only the elite could afford. There were even laws that prohibited commoners from owning such dogs or entering certain hunting grounds.

A Hunter and Dogs Pursuing a Hare, about 1430–40, Unknown illuminator. Tempera colors, gold paint, silver paint, and gold leaf on parchment, 10 3/8 x 7 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 27, fol. 85

The greyhound was particularly favored for its aristocratic appearance as well as its admirable speed, and owning a greyhound was a reflection of the owner’s princely nature. Thus, presenting them in front of guests at banquets was a way of showing off one’s wealth, power, and taste.

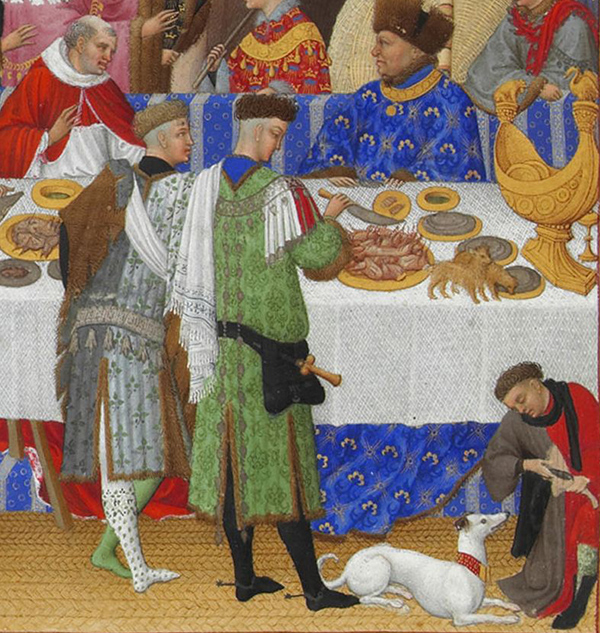

January (detail) in Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, 1412–16, Limbourg Brothers. Pigment on vellum, 8.9 x 5.4 in. Musée Condé, Chantilly

In one famous illumination in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, one of the greatest 15th-century manuscripts (held in the collection of the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France), a greyhound can be seen on the floor in front of the banquet table. There’s no doubt that this princely dog is intended to reflect the Duke of Berry’s high status. Joining the fun are two small dogs who stand on the table amongst the food.

Designed to teach a lesson on temperance, another dog-rich illumination from the Getty’s collection reflects the view of the greyhound as an aristocratic, noble beast. An upright hound stares at a group of rowdy peasants, looking *very* disapproving.

Waste Pick-up, Canine Style

Fu veramente piacevol il convito fatto dalli signori Piacevoli servi di V.A.S. (detail), 1627, Stefano Della Bella. Etching. The Getty Research Institute, P910002

Another reason dogs were a common presence at feasts? Waste management. Dogs could be frequently seen roaming around banquet halls, eating food scraps thrown on the ground. The image above shows a guest at the table turning around slightly as if to pat or feed a dog standing on its hind legs, looking earnestly at the man. Another hungry dog stands in front of the table, appearing forlorn.

In a world without garbage disposals or municipal trash pick-up, leftover food was often given to servants or the poor as an act of charity—or fed to animals, such as pigs or dogs.

Freÿ Taffel der M.D: dreÿ obern H.n. Ständten (detail), 1740, Georg Christoph Kriegl. Engraving and etching. The Getty Research Institute, 1383-190

The image above shows a dog next to a servants’ HQ. Gathered in front of a few baskets, servers appear to be scraping food off plates or loading them up for the next course. The presence of the dog reflects its role in polishing off food scraps. The term “doggie bag” has its origins in this long association of dogs and leftovers.

Freÿ Taffel der M:D: dreÿ obern H.n. Ständten, 1705, Christian Engelbrecht (engraver), Ludwig von Gülich (author), Johann Cyriak Hackhofer (draftsman), Johann Andreas Pfeffel (engraver). Engraving, etching. The Getty Research Institute, 87-B14573

There’s one more way to explain the frequent appearance of dogs in banquet scenes from centuries ago: Dogs were ubiquitous then, just as they are now. From hunting helpers to food vacuums, dogs weren’t just pets, but hard-working members of the household.

_______

See many of these artworks in Eat, Drink, and Be Merry: Food in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, on view October 13, 2015, to January 3, 2016, at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center and The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals on view October 13, 2015, to March 13, 2016, at the Getty Research Institute.

Enlightening- Do dogs today, have the same status? I see where the president in the United States of America would got a dog.