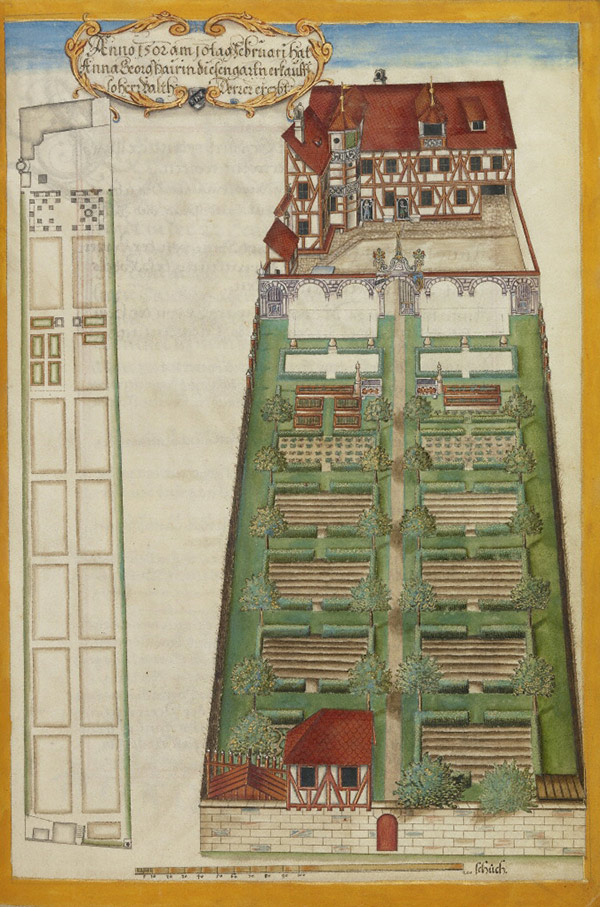

The Nuremberg Residence and Garden of Magdalene Pairin, about 1626–1711, Georg Strauch. Tempera colors with gold and silver highlights on parchment, 14 13/16 x 10 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.MP.155.130bisGardening is…well…as old as grass, and while we may have modern innovations like hybrid seeds, tractors, and automatic irrigation systems, the gardens of today aren’t that much different from those of the Renaissance. Many of the fruits and vegetables we enjoy today were commonplace in a Renaissance garden. The only difference is perhaps that in that period (about 1350 to 1600 in Europe), much of the produce grown was part of a peasant diet, while meats were reserved for the upper classes. Now, low-income communities are offered fast-food chains instead of vegetable stands in areas considered to be “food deserts.”

Vegetables were truly side dishes, in the sense that root crops like carrots, beets, parsnips, and turnips were generally used to flavor meats while cooking. Salads, including cress, mustard greens, beet greens, and herbs were used to accompany meals. A typical Renaissance garden also featured some of our favorites:

Cabbage—A favorite for stews with marrow bones. Here in Los Angeles, we grow this during the cool season, planting in fall or early spring.

Leeks and onions—Still staple ingredients today, these alliums were grown regularly to flavor dishes of the time. Today we use onions to ward off pests in the garden by planting them in between other crops like lettuces and kale.

Broad beans and peas—Peas are grown in the cool season (fall or early spring in L.A.) and beans in warmer weather to be eaten fresh or dried for later use.

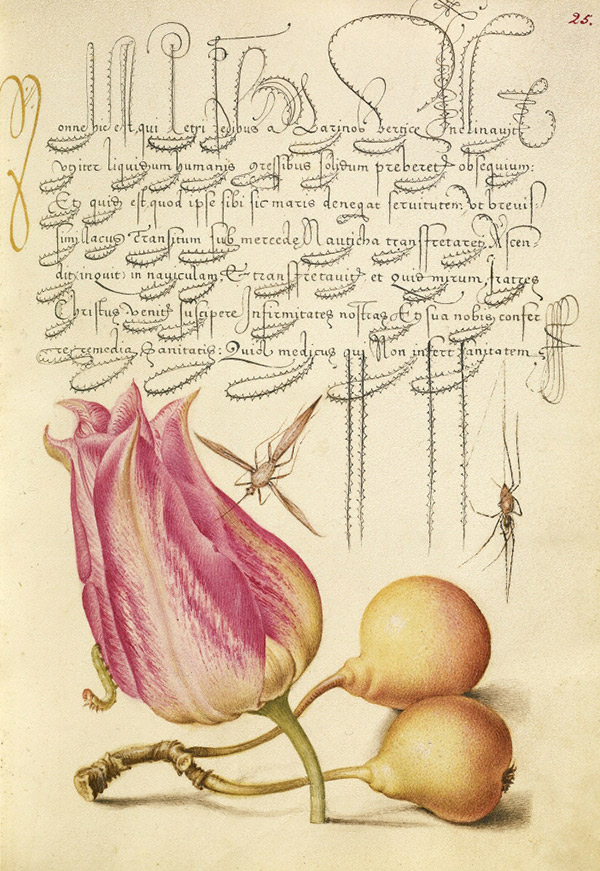

Gourds and squash—Pumpkins and squashes of all sorts are depicted in Renaissance paintings and were grown, as they are today, in warmer weather. Recipes have been found showing unusual ways to serve squash, including a dish where the squash is boiled, then battered in salt and flour, then fried in oil and served with a garlic sauce and breadcrumbs.

Fly or Blister Beetle, Willow Bellflower, Gourd, and Bindweed in Mira calligraphiae monumenta, 1561–62, Joris Hoefnagel, illuminator, with calligraphy added by Georg Bocskay, 1591–96. Watercolors, gold and silver paint, and ink on parchment, 6 9/16 x 4 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 20, fol. 4

Fruits of the Renaissance garden will also be familiar to modern-day cultivators. While the varieties may be different now, a typical orchard might contain:

Figs—This fruit has a long history dating back to as far as 2500 B.C. It was grown during the Renaissance for fresh eating, and could be dried for storage.

Pear and apples—Both were cultivated (though the pear transitioned from wild to cultivated during the 17th century). They could be made into jams, and apples would be baked into tarts while pears were often cooked in mead.

Insect, Tulip, Caterpillar, Spider, and Pear in Mira calligraphiae monumenta, 1561–62, Joris Hoefnagel, illuminator, with calligraphy added by Georg Bocskay, 1591–96. Watercolors, gold and silver paint, and ink on parchment, 6 9/16 x 4 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 20, fol. 25

Strawberries—For a time, it was not considered safe to eat fruits raw, so like pears, strawberries were cooked in wine with spices such as cinnamon and ginger. Strawberries are native to Europe, and appear frequently in art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. There are “ever-bearing” and “June-bearing” varieties that produce, respectively, over several months or all at once in the spring.

Melons—Another ancient fruit that threatened or ended the lives of many including kings, the melon carried with it a dangerous reputation. Still, the regal rallied around it and kept it in fashion.

Edible gardens of the Renaissance were as much about pleasure as they were about sustenance. Today, we aspire to recreate the abundance depicted in paintings of days gone by for our own enjoyment. Here’s a good source for some interesting recipes from the Renaissance, if you’d like to try your hand at it.

Text of this post © Christy Wilhelmi. All rights reserved.

Dear Dr. Wilhelmi,

I have recently become interested in the festal scenes from the Nastagio degli Onesti series by Botticelli–the forest scene and the wedding banquet. But what are the guests eating? Are the foods in any way typical to banquets? They don’t seem to me to be. In the wedding scene, the guests seem to have tiny berries scattered directly on the table in front of them, which they perhaps are using tiny forks to spear. In the forest scene, things that look like scallions and cucumbers as well as many rolled cylinders are scattered on the table, while a bowl of something that looks like ice, diamonds or pearls has been spilled on the ground.

If you have any thoughts on this, I’d love to hear them!

Best,

Karen