Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.—Ed.

Werner Herzog, the great Bavarian explorer, is on a never-ending search for ecstatic truth, which he defines as “the deepest essential that defines us as human beings.” In the case of his video installation Hearsay of the Soul, Herzog gives us room to practice our own truth-seeking by introducing two like-minded visionaries: 17th-century painter of invented landscapes Hercules Segers and 21st-century avant-garde cellist and composer Ernst Reijseger. With this installation, Herzog has assembled a lesson in landscape, sound, and soul.

Installation of Hearsay of the Soul at the Getty Center. Hearsay of the Soul 2012, Werner Herzog. © Werner Herzog. Music by Ernst Reijseger from the albums Requiem for a Dying Planet (Winter & Winter, 2006) and Cave of Forgotten Dreams (Winter & Winter, 2011); film excerpt from Werner Herzog’s Ode to the Dawn of Man (2011), featuring Ernst Reijseger (cello) and Harmen Fraanje (organ); sound producer: Stefan Winter

Herzog has described the soul as the part of us that, in the presence of great works, “completes an independent act of creation.” In Hearsay of the Soul, Segers and Reijseger morph as equals across five screens, and so do we. We become part of the landscape, and feel the ecstasy oozing out of Segers and Reijseger for ourselves.

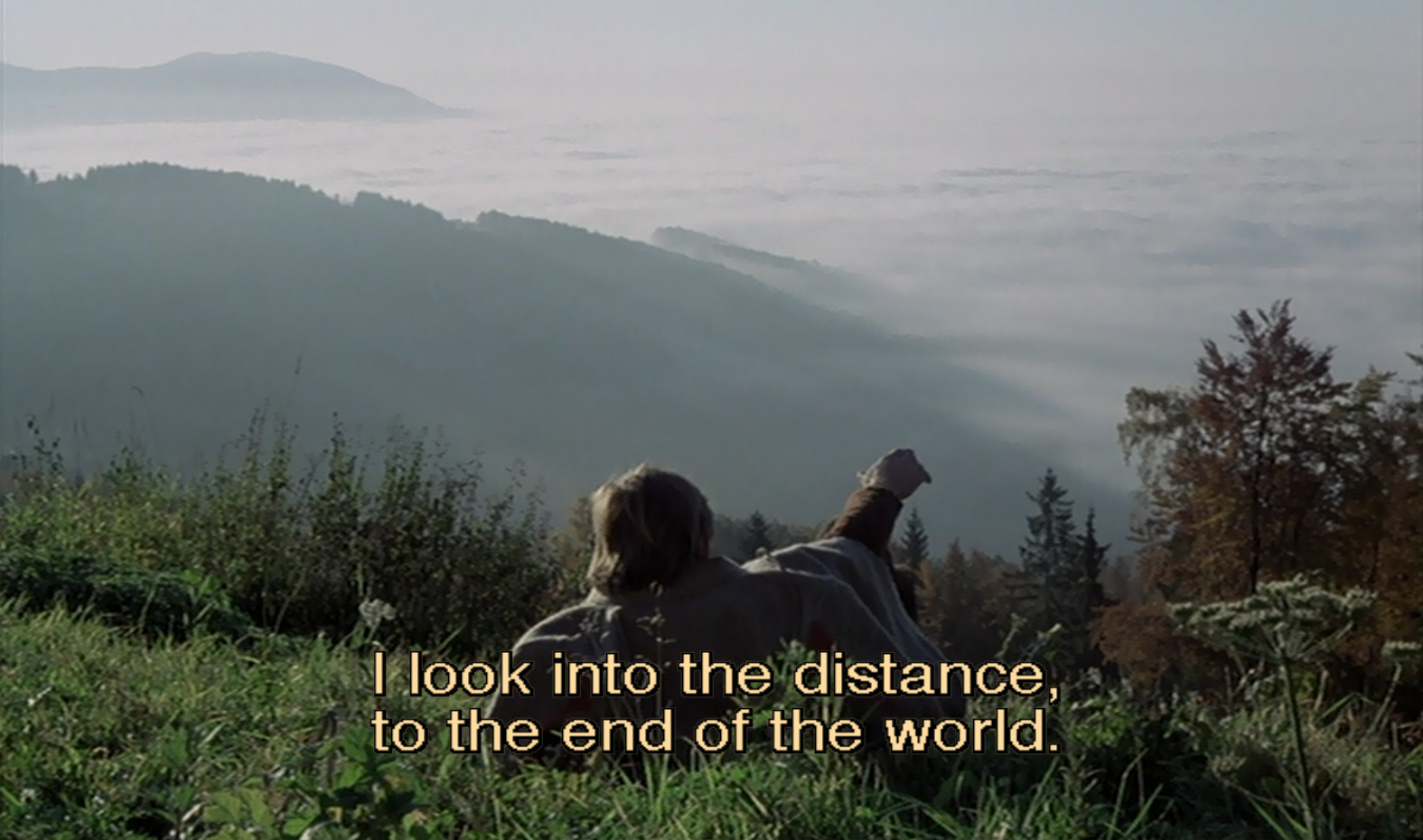

As someone who has felt strong affinity for Werner Herzog’s films over the years, I can’t help but think back to the many other instances in which I’ve witnessed Herzog pull off such ecstatic combinations of music and environment. A wide range of early and late examples come to mind: listening to Leonard Cohen as we span the Saharan roadside in Fata Morgana (1971); the hypnotic fog in Heart of Glass (1976); Siberian throat singing coupled with footage of bombing raids over Vietnam in Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997); and even an entrancing choir that follows a deranged penguin toward the mountains of Antarctica in Encounters at the End of the World (2007).

Landscapes and music act as equal partners in Herzog’s films, creating an experience greater than the sum of its parts. “Images and music somehow complement each other, they form a separate reality,” he told me on Saturday.

Still from Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972). © Werner Herzog Filmproduktion

Herzog considers music the closest art form to cinema, so it’s natural that he sometimes starts a film with the music first—or would give ten years of his life to be able to play the cello or another musical instrument.

Herzog’s unrelenting quest for worthy landscapes has taken him to every continent, through snow, jungle, and fire. He has even explored time—as far back as 30,000 years ago—and reached out to outer space. During a recent film series, the British Film Institute even went as far as to create a Google map of globetrotting Herzog productions.

The point of Herzog’s quest, however, is not to visit every continent, much less play games of mere aesthetics. It is to create images, thoughts, and urges that linger deep inside, years after you’ve watched one of his films. Images as small as radioactive albino alligators at the end of Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) may suggest a time when humans are no longer in existence; one as massive as a 350-ton ship being dragged over a hill in the Amazon in Fitzcarraldo (1982) evokes humanity’s drive for the impossible.

“For me a true landscape is not just a representation of a desert or a forest. It shows an inner state of mind, literally inner landscapes, and it is the human soul that is visible through the landscapes presented in my films.” —Werner Herzog

________________

UPDATE: Here are some suggestions for a few “double feature” pairings of Werner Herzog films and those of other directors, if you’re game to seek them out:

Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982)

Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979)

Werner Herzog’s Fata Morgana (1971)

Hubert Sauper’s Darwin’s Nightmare (2004)

Werner Herzog’s Stroszek (1977)

David Lynch’s The Straight Story (1999)

Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979)

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre (1989)

Werner Herzog’s Land of Silence and Darkness (1971)

and (yes, I know) Hearsay of the Soul (2012)

________________

Herzog and Reijseger: From my interview, here’s a video of Werner Herzog talking about Ernst Reijseger. Herzog spoke to us in the Green Room just before his appearance on stage on August 3, 2013; Reijseger, meanwhile, had a bit of fun with impromptu performances around the Getty Center during the days leading up to the event.

Comments on this post are now closed.