Coats of arms in the Getty manuscripts collection

Numerous illuminated manuscripts in the Getty collection feature coats of arms, signs of prestigious ownership from the distant past. These heraldic devices feature on books made for guilds, knights, cardinals, bishops, dukes, families united by marriage, humanists, royal advisors, and young women.

This post is the first in an occasional series that shares insights into the lives of some of the illustrious patrons from medieval and Renaissance Europe, and also explores mysteries that still remain about some of the more enigmatic emblems and devices.

A Mystery Resolved

For our first mystery, let’s look at a tiny (4 1/2 by 3 1/4-inch) 15th-century French book of hours, or personal prayer book, in the Getty collection. This is the final section of a magnificent manuscript that was divided at some point into three separately bound books. Scholars identified the Getty manuscript as a long-lost volume from this work through the text and the outstanding quality of the illuminations by Jean Fouquet, who worked for Kings Charles VII and Louis XI of France. The other two volumes are now in the National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague.

While this identification alone is worthy of celebration, manuscript specialists were also able to identify the original patron of the book by decoding the coats of arms included in numerous illuminations throughout the three volumes.

The Virgin and Child Enthroned; Simon de Varie Kneeling in Prayer, Jean Fouquet, Hours of Simon de Varie, Paris, 1455. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 7, fol. 1v-2

The coats of arms are badly damaged in the volumes at The Hague, and those in the Getty volume were overpainted in the 1600s with the arms of the Bourbon-Condé royal family, obscuring the original details. With the help of a microscope, ultraviolet light, and infrared reflectography—the Getty never performs invasive or damaging tests on manuscripts—art historian James H. Marrow was able to determine the content of the original coat of arms: three silver helmets on a red shield, with a gold star in the center. In heraldic terms, this is described as gules, three helmets argent, at the fess point an estoile; or to use the original French heraldic terms, de gueules à trois heaumes d’argent accompagnés d’une étoile d’or en abîme.

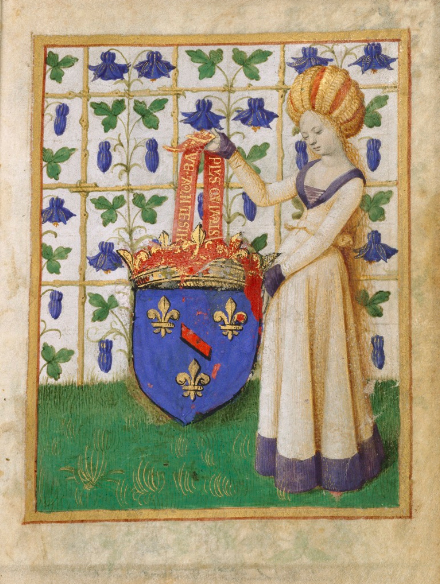

Coat of Arms Held by a Woman, Jean Fouquet, in Hours of Simon de Varie, made in Paris, France, 1455. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 7, fol. 1. Here the original coat of arms has been covered by the arms of the Bourbon-Condé family.

Despite this breakthrough, another mystery emerged: the specific coat of arms had yet to be identified with a particular family. That is, until François Avril, the preeminent former curator of manuscripts at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, located the crest in the vaulting of the chapel of the Hôtel Jacques Coeur in Bourges. Along with examples from document seals, Avril connected the crest in the manuscript with the Varie (or Varye) family.

Given that the gold star is a heraldic device to denote younger members of a family, Avril was even able to pinpoint Simon de Varie, younger brother of Guillaume de Varie—whose arms appear in the chapel of the Hôtel Jacques Coeur—as the patron. Avril confirmed the theory by noting that the motto used in the manuscript VIE A MON DESIR (life according to my desire) is an anagram of SIMON DE VARIE.

All of these combined efforts truly represent an art historical success story.

…And A Mystery to Conquer

Let’s turn our attention to another manuscript mystery—one that has yet to be solved.

A Young Knight in Armor Kneeling in Prayer before Saint Anthony, Dreux Jean, in The Invention and Translation of the Body of Saint Anthony, about 1465-70. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 8, fol. 50

On this manuscript page, a handsome knight with long hair and shiny armor kneels in perpetual prayer and veneration before Saint Anthony Abbot of Egypt, whose life and posthumous miracles are recounted and wondrously visualized in the manuscript.

The patron’s enigmatic coat of arms features on several decorated pages of the rather short book, either emblazoned on a shield topped by a helmet and held by an angel (whose wings mirror the fleurdelisé pattern on the escutcheon) or held by a lion as a banner or standard. In heraldic language, the arms can be described as follows: Sable Quarterly I and IV fleur-de-lis Or, II and III fretty Argent. These devices declare the early owner’s identity and yet have simultaneously resisted decipherment, befuddling scholars.

A Young Knight in Armor Kneeling in Prayer before Saint Anthony (details), Dreux Jean, in The Invention and Translation of the Body of Saint Anthony, about 1465-70. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 8, fol. 50

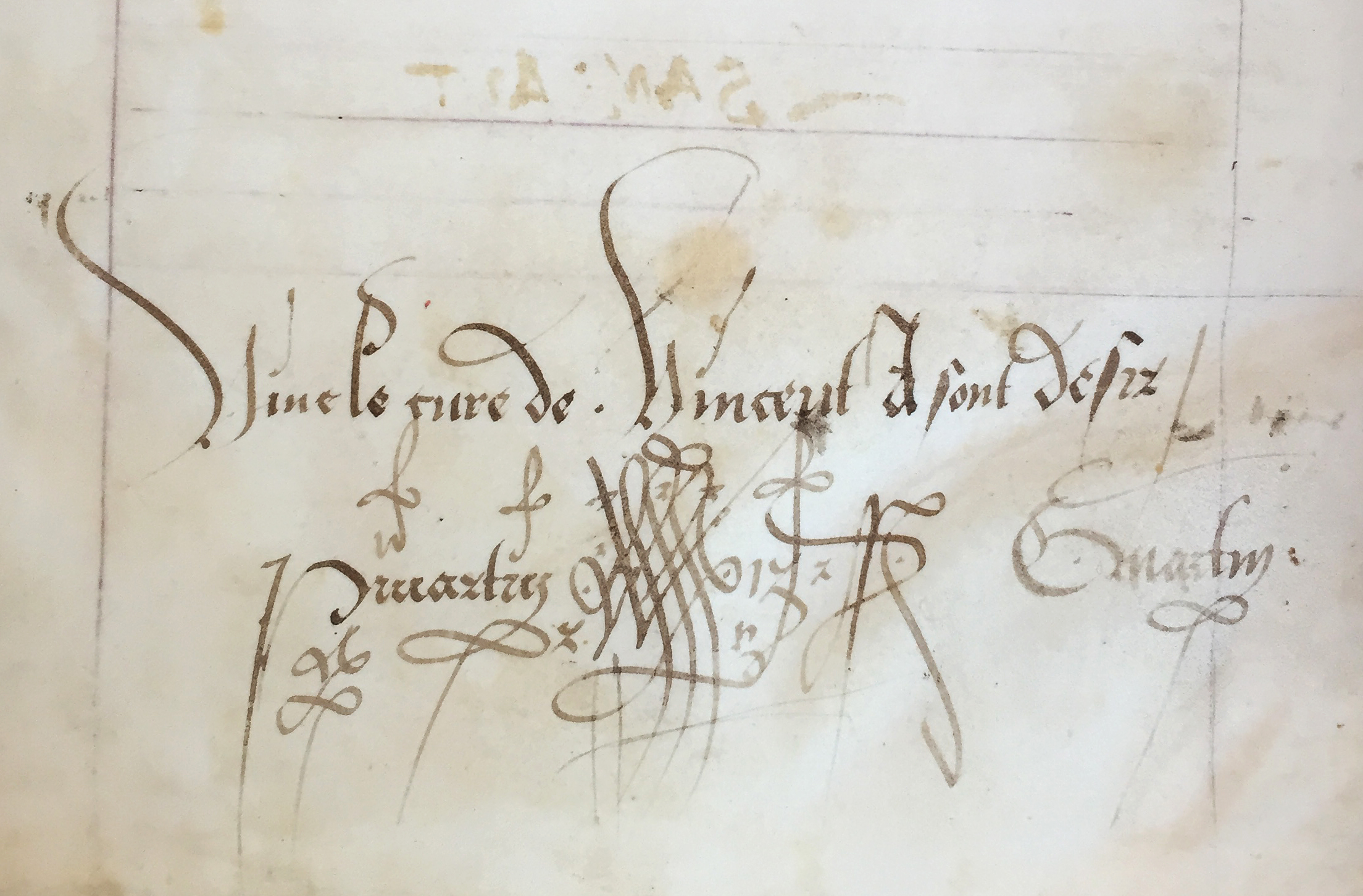

The knight’s motto, however, can be easily read: Du bien d’elle, a French phrase that may be translated as “Of her goodness,” perhaps referring to a bond or vow taken for a lady by a knight devoted to a chivalric order dedicated to Saint Anthony. Additionally, a puzzling phrase was penned, presumably in a 15th-century script, on the last page (folio 56v) of the manuscript: Vinc (Vive) le curé de Vincent à sont desir // P Martin [monogram] GMartin. The same hand likely also wrote Girin Martin Prothon(otaire) (?) seen at the end of the post.

What are we to make of these marks and beguiling inscriptions? We welcome your insights and suggestions!

Possibly “Vinc (Vive) le curé de Vincent à sont desir // P Martin [monogram] GMartin,” probably Bruges, Belgium, about 1465-70, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 8, fol. 56v

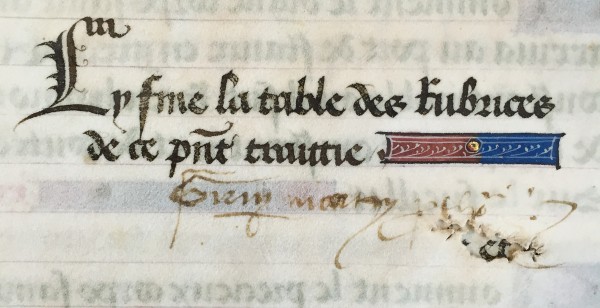

Possibly “Girin Martin prothonotaire,” probably Bruges, Belgium, about 1465-70, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 8, fol. 5

Further Reading

The Hours of Simon de Varie, James H. Marrow, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1994. Pages 3–11 cover the rediscovery of the volume now in the Getty collection and the identification of its original patron.

Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrick, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003. Pages 213–215 discuss the manuscript and provide additional bibliography.

“II and III fretty Argent” were used by the northern English Harringtons. I don’t know what connection they would have with a book that had a succession of Belgian owners. Perhaps that’s barking up the wrong tree?

Re Saint Anthony, I received this article via a Google Alert. In an effort to assist, it would be appreciated if you will provide a list of any publications or other sources that you have reviewed, are reviewing, or are aware that others have reviewed.

Regards,

Jeff

Hi Jeff,

I’m Rheagan Martin, one of the authors of this blog post and a curatorial assistant working with manuscripts at the Getty Museum. Here is a bibliography of sources that cite the Getty’s manuscript specifically. However, it is not an exhaustive bibliography on Saint Anthony. Please do let us know if you see the Getty’s manuscript cited anywhere else!

Schnitzler, Herman. Grosse Kunst des Mittelalters aus Privatbesitz, exh. cat. (Cologne: Schnütgen-Museum, 1960), p. 77, no. 113, figs. 94-95.

Legner, Anton. “Zur Präsenz der grossen Reliquienschreine in der Ausstellung Rhein und Maas.” In Rhein und Maas: Kunst und Kultur 800-1200, 2 vols. (Cologne: Schnütgen-Museum, 1973), vol. 1, pp. 65-94.

Euw, Anton von, and Joachim M. Plotzek. Die Handschriften der Sammlung Ludwig. 4 vols. (Cologne: Schnütgen-Museum, 1979-1985), vol. 3 (1982), pp. 82-88.

“Manuscript Acquisitions: The Ludwig Collection.” The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 12 (1984), p. 298.

Touwaide, Alain. “Visions du monde médiéval à travers les manuscrits enluminées du J. P. Getty Museum (Malibu).” Scriptorium 45, no. 1 (1991), pp. 298-302.

Zimmermann, W. Haio. Pfosten, Ständer und Schwelle und der Ubergang vom Pfosten-zum Ständerbau-eine Studie zu Innovation und Beharrung im Hausbau: zu Konstruktion und Haltbarkeit prähistorischer bis neuzeitlicher Holzbauten von den Nord- und Ostseeländern bis zu den Alpen. (Oldenburg: Isensee Verlag, 1998), pp. 180-92, fig. 107a.

Kren, Thomas, and Scot Mckendrick, eds. Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003), pp. 213-15, no. 50, entry by Thomas Kren.

Morrison, Elizabeth. Beasts: Factual & Fantastic (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: The British Library, 2007), pp. 45, 47, fig. 35.

Inglis, Erik. Faces of Power & Piety (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: The British Library, 2008), pp. 68-69, fig. 61.

Kren, Thomas. Illuminated Manuscripts from Belgium and the Netherlands in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010), pp. 70-71, ill.

Sciacca, Christine. Building the Medieval World (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: The British Library, 2010), p. 60, fig. 57.

Schandel, Pascal. “Le Maître aux grisailles fleurdelisées.” In Miniatures flamandes 1404-1482, exh. cat. Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt, eds. (Brussels: Bibliothèque royal de Belgique; Paris: Bibliothèque national de France, 2011), pp. 372-73, fig. 274.

I am not by any means an expert in heraldry, but from what I see here, there are clues to the identity of the person who bore these arms, which I think you have blazoned incorrectly. This should, by the usual rules, represent the offspring of a marriage alliance between two armigerous houses. The father bore the following: Arms: Sable, a fleur-de-lis or. Crest: A demi angel proper erased (possibly couped, it’s hard to tell from the illustration), robed gules, wings displayed and inverted sable, seme-de-lis or, regarding a demi fleur-de-lis or held before him in both hands. The mother, who had to be an heraldic heiress (had no brothers to inherit her father’s arms), bore: Arms: Sable, fretty argent. Crest: unknown. The complete blazon would be: Arms: Quarterly, I and IV, Sable, a fleur-de-lis or. II and III, Sable, fretty argent. Crest: A demi angel proper erased, robed gules, wings displayed and inverted sable, seme-de-lis or, regarding a demi fleur-de-lis or held before him in both hands. The barred helmet indicates someone from the highest ranks of the aristocracy. I would start looking in France. The French royal house bears Azure, seme-de-lis or (ancient) or Azure, three fleur-de-lis or (modern) Since changing the tincture of the field or the number of charges are common ways of differencing arms, I would start looking for the father’s arms among the offshoots of the French royal house. It would then be necessary to follow that line until you find the marriage with the heraldic heiress who bore Sable, fretty argent. Their son would be the owner of the arms in question. I would think that the young knight in the illustration is intended to be the bearer of the arms. The illuminator of the manuscript appears to have taken liberties with the mantling of the arms. They should be sable lined or, but he has changed them to azure lined gules to blend in with the rest of the illumination on the page. There might be a remote possibility that the lion bearing the banner may be a reference to the crest accompanying the mother’s arms, otherwise not shown by the illuminator of the manuscript.

Whenever you run into a question of coats of arms or armorial bearings, I recommend that you contact the College of Arms (England). They are the institution which grants coats of arms, etc. in England. They could probably refer one to the equivalent institutions for other many other countries. I would imagine that they would possess some of the best collections of records of previous grants of arms to individuals and corporations.

Heraldic rules in France during the 1400’s-

These are based on Bonet’s Arbre des Batailles(1387).

“There are certain barons, and other gentlemen, whose predecessors had their arms by gift of the Emperor, or by gift or privilege of kings: Hence our masters said that such arms should not be borne by one not of that blood. And I hold this true, if it be understood of that country which is subject to him who has bestowed the arms. But if the king of France had given a silver lion to my line, what harm would result if Germans in Germany bore similar arms? They would certainly not be punished by law.

We have another kind of arms that a man assumes at his pleasure. You must know that men’s names were invented to show the distinction between persons. Such names any man may choose at pleasure, either the father for his son of the godfather for his godson. And further, a man may change his name, provided he does not do so dor purposes of fraud but merely to have a pleasanter name. The same is true of arms. So, such arms as may be chosen at pleasure each may take as he wishes, and may have them painted on his horse and on his belongings, but not on the belongings of others.”

In order to determine if any coats of arms of French nobility of those times matched the arms in the manuscript, I reviewed all of the arms in the major and other armorials that were contemporary with the arms in question. The major ones were Grand Armorial de la Toison d’Or, and Armorial de Gilles Le Bouvier. There was no match. This is significant because the Lion supporter in the manuscript is reserved for knights known for leadership and accomplishment, or royalty. The fact that the armorials do not include the arms in the manuscript indicates that it represents a non noble, or non royal. That is why the article you included states that the manuscript coat of arms is “unusual”.

The coat of arms in question (Sable Quarterly I and IV fleur-de-lis Or, II and III fretty Argent) should be viewed with respect to its symbolism. The fleur-de -lis is a symbol of France. Multiple frettes(Fretty) form a net. This multiple design is defined by the herald J.P. Brooke- Little in his book Colour of Heraldry as “something mal traverse or difficult to get through”. It is a protective representation. Please view the attached illustration from his book. When the fleur-de lis is connected with the frette, this association may be interpreted as defense of France.

You have written “Du bien d’elle, a French phrase that may be translated as “Of her goodness,” perhaps referring to a bond or vow taken for a lady by a knight devoted to a chivalric order dedicated to Saint Anthony.” This may be correct in using the phrase at an individual level. Aside from this phrase being displayed on a pole with the coat of arms as a banner, on fol.29 the coat of arms and the phrase are being displayed on a standard. Men in combat followed their standard. Perhaps the phrase refers to La France.

Modified heraldic achievements appear in fols.6,10,29, and 50. In each, the fleur-de-lis winged angel is in a different position with regard to hands and head. A comparison of the four indicates various hand movements on the large fleur- de-lis. This hand held fleur –de-lis symbol also appears in early and contemporary armorials, such as the Armorial Le Breton ca. 1300. This example depicts a coat of arms with a seated king holding a scepter and a hand held fleur- de- lis(dominion over the land of France).Also, please see the Charles VII Royal D’Or. In fol. 6 the angel’s garment is stretched over the helmet with the fleur-de-lis resting on top. This indicates that the angel brought the fleur-de-lis from heaven and placed it on the helmet(God is on the side of France).