An unabridged version of this paper is available as a PDF here.

Untitled, 1971, Robert Mapplethorpe. Wood, paper, papier-mâché, glass, cellulose nitrate (with camphor), nylon, metal, rabbit’s foot, liquid, and other plastics, 6 x 6 1/2 x 6 1/2 in. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Held at the Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20.45

In February 2011 the Getty and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) announced a joint acquisition of archival materials and works by, or associated with, Robert Mapplethorpe. Although Mapplethorpe’s fame derived from photography, he did not consider himself a photographer, but an artist: during his studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in the 1960s, he only took classes in painting and sculpture, and majored in graphic art. It was not until 1971 that he found his interest in photography, after he borrowed a Polaroid camera to advance his work with collage, which he had previously made using magazine clippings.

A goal of the Getty Research Institute is to collect individual artists in depth and to show the development in an artist’s oeuvre. For that reason, the Research Institute is very interested in Mapplethorpe’s early and therefore formative years, between 1968 and 1972, when he created many 3D objects and jewelry designs.

The Object

Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Held at the Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20.45

One of these untitled Mapplethorpe pieces from 1970/1971 is a lidded box (shown above) that houses an altered snow globe.

The box is made from wood laminated with decorative papers and plastic sheets as an outer protection layer. Along the left and right edges, the frontal sides are profiled through a convex expansion of the paper/plastic layer. The hollow areas between the paper and the wood are filled with papier-mâché.

The inside of the box is lined with a fine textile, and a hollow cylinder is mounted to the middle of the box to hold the altered globe in place. This snow globe has additional pieces, a rabbit’s foot and a small red painted object, encased in a nylon stocking and held in position by ribbons wound around the outside of the stocking. The globe, further, has a fringe trim attached to the bottom. Metal hinges keep the box closed.

Our Preservation Approach

When the box came into the special collections of the Getty Research Institute, it showed minor damage at the proper left front edge, where the paper/plastic layer had separated from the weakened papier-mâché carrier and lifted.

Left: Damage to the left front of the box. Right: Detail of the damage, with centimeter rule for scale

Before undertaking any kind of action, we investigated the object’s materials. Tom Learner’s science team at the Getty Conservation Institute generously undertook analyses of the plastic sheets, which were determined to be cellulose nitrate (CN) plasticized with camphor. (See full paper for data obtained from this analyses.)

In order to stabilize the lifted CN/paper layer, we decided to create a sticky film that would function as a double-sided tape between the lifted parts and the wood/papier-mâché layer. It would prevent the introduction of any solvents that might cause discoloration of the tinted paper, or water and its vapors, which have an impact on CN materials.

To verify our approach, we undertook a series of tests on facsimiles that imitated the object’s mixed materials.

Facsimile of cardboard, blotting paper, colored paper, and domed Mylar®

The facsimiles would help us understand possible re-attaching issues and handling requirements.

These tests led us to choose the acrylic dispersion Lascaux® 360 HV. It is not only stable while aging, and so does not yellow or release any harming vapors, but it also remains sticky after it has dried to a clear film.

We created an evenly thinned adhesive film in a mould made from Mylar® strips that allowed a steady adhesive application onto a siliconized plastic carrier. Siliconized plastic sheets appeared to be the best carrier since uncoated foils made it harder to release the dried film onto an object. To ease its loosening, we activated the film with fast-evaporating solvents such as acetone.

Top: Mold of Mylar® strip adhered on silicone-coated carrier using double-sided pressure-sensitive tape. Bottom: Adhesive application onto the mold to create the adhesive film

In order to ensure proper adhesion between the papier-mâché and the adhesive tape layer, we consolidated the fragile papier-mâché. We preferred Lascaux® Medium for Consolidation over very low-viscose wheat paste, which is commonly used for consolidating paper materials. The wheat paste tended to remain at the surface, whereas the Lascaux® Medium for Consolidation penetrated deeply and locally to the bottom of the blotting paper.

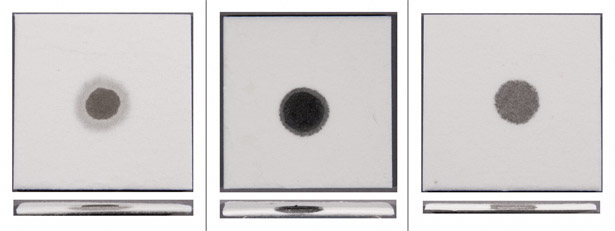

Left to right: Wheat paste on blotting paper, dyed black; Paraloid B-72 on blotting paper, dyed black; and Lascaux® Medium for Consolidation on blotting paper, dyed black

Comparing consolidated blotting paper (left) with non-consolidated blotting paper (right)

The treatment on the Mapplethorpe box led to a satisfying result, which will be monitored long-term to reach a final conclusion.

Mapplethorpe’s box after treatment. At right, a detail of the treated corner.

For a more detailed discussion of this project, please see the full paper.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Mary Reinsch-Sackett, head of the Getty Research Institute’s Department for Conservation and Preservation, for the time I was able to spend on this research project, as well as John Kiffe, photographer in the Research Institute’s Digital Services Department, for providing me with high-quality images of the various Mapplethorpe pieces. Furthermore, I want to thank Tom Learner, Head of Science at GCI, for the time his lab spent analyzing plastic samples.

See all posts in this series »

Well done! Interesting read!