As season 4 of the dystopian drama hits the air, we recommend medieval books its lead characters would do well to consult

Gathering Twigs in a Book of Hours, about 1550, Simon Bening. Tempera colors and gold paint on parchment, 2 3/16 x 3 ¾ in. (5.6 x 9.6 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 50, verso

Winter is coming. Not literally of course—the cold has had its grip on many parts of the world for months—but Game of Thrones fans know what I mean. With season 4 upon us, I’m getting prepared for all of the adventure, plot twists, love stories, and of course death that the proverbial coming winter has in store for the show’s characters.

Taking a Page from Medieval Manuscripts

The gripping narratives, intricate web of characters, and strange lands from the bygone yet parallel world of Game of Thrones could have emerged directly from the pages of illuminated manuscripts. Kings clashing for a throne, steamy romances against a backdrop of gruesome violence and betrayal, and mythical creatures that captivate the mind and frighten the timid spirit have become synonymous with the Middle Ages and are mainstays of the Game of Thrones plot.

The resonances between our own imagined view of the Middle Ages and how medieval people actually saw themselves is a recurring theme in our manuscripts exhibitions at the Getty—from fantastical beasts and mischievous marginalia to architecture, portraiture, fashion, and gardens.

For me, browsing the images from manuscripts featured in those exhibitions and throughout the Getty collection immediately evokes episodes from George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones saga. If you’re a fan of the show, doesn’t the naval battle in the miniature below remind you of the Battle of the Blackwater, a decisive confrontation between two branches of the Baratheon family (one of the great families of Westeros, the fictional continent akin to Great Britain)?

Of course, the illumination does not include the green sparks of wildfire exploding in the night sky that led the minor branch to victory, but the artist, Lieven van Lathem, does include spurts of blood, a figure about to jump aboard an enemy ship, clashing swords, and lifeless bodies afloat in rough waters. This image is just one of numerous examples that reveal the medieval-ness of Game of Thrones.

A Naval Battle Between Gillion’s Troops and the Soldiers of the Saracen Prince in The Romance of Gillion de Trazegnies, Lieven van Lathem. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 14 9/16 x 10 1/16in. (37 x 25.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 111, fol. 21

For the academic, the interwebs already feature numerous blog posts dedicated to the historicity or historical resonance of Game of Thrones (my favorite being Ohio State University’s day-long event dedicated to the historical-cultural themes in the book’s fictional universe), while wikis offer die-hard aficionados a forum to geek out on sigils, dragons, and the mechanical map seen in the opening credits.

As a medievalist and manuscripts specialist, I couldn’t resist the temptation to pair my favorite show with my favorite artworks and draw up some reading recommendations for a few aristocratic characters—beloved and despised alike—from the Seven Kingdoms. Although the ghouling, blue-eyed, mummy-like White Walkers from the polar lands of Westeros will soon threaten all humankind, if the Game of Thrones characters were to read some of the great medieval texts recommended in this post, following the example of medieval aristocrat Denise Poncher, shown below, who reads from the medieval bestseller known as the Book of Hours—then they too might be able to withstand the frightening trials that are in store. All men must die…unless they brush up on their manuscripts.

Denise Poncher before a Vision of Death, Master of the Chronique scandaleuse. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 5 ¼ x 3 7/16 in. (13.3 x 8.7 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 109, fol. 156

Book Picks from the Getty Shelves

Ex libris (From the library of…)

Arya of the House Stark

Princess of Winterfell

Combat with Dagger and Staff; Aiming Points on the Body, from Fiore dei Liberi, The Flower of Battle, possibly Venice or Padua, about 1410. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 11 x 8 1/8 in. (27.9 x 20.6 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 13, fols. 31v–32

Who She Is

The youngest daughter of the Stark family, princess Arya from the northern realm of Winterfell shirks traditional gendered activities like embroidery and takes up a sword. By season 3 of Game of Thrones she has become quite the swashbuckler and even vanquished several foes with her blade, Needle.

What She Needs to Read

Here’s a book that would show even Arya a few new tricks: The Flower of Battle (Fior di Battaglia), dedicated to the arts of fighting with weapons, on foot and on horseback. Medieval knights were extensively trained in how to wield swords and daggers of various sizes, and this book is a remarkable how-to manual (but, please, don’t try the techniques at home!).

The page at left above shows different approaches to combat with daggers and staffs, while the facing page at right discusses seven aiming points for sword combat, highlighting four virtues that are crucial for one to become skilled with the sword: depth perception (represented by the lynx at top), swiftness (as a tiger at left), courage (of the lion at right), and strength and balance (in the figure of the elephant at bottom). Arya would no doubt substitute a direwolf, the heraldic animal of House Stark, as the full embodiment of each of the swordsmith’s virtues.

Aiming Points on the Body, from Fiore dei Liberi, The Flower of Battle, possibly Venice or Padua, about 1410. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 11 x 8 1/8 in. (27.9 x 20.6 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 13, fols. 31v-32

Bran of the House Stark

Prince of Winterfell

The First The Seventh Seal: An Angel Censing an Altar and Pouring the Censer over the Earth; Trumpet: Hail and Fire Fall From Heaven in the Getty Apocalypse, English, probably London, about 1255–60. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and colored washes on parchment, 12 9/16 x 8 7/8 in. (33 x 24.1 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig III 1, fols. 10v–11

Who He Is

Younger brother to Arya and second youngest of the Stark family, Bran was mercilessly paralyzed after being pushed from a window as punishment for witnessing an incestuous affair between a brother and sister from another clan. He later discovers that he is a warg, a creature that can enter the minds of animals.

What He Needs to Read

Bran might find a kindred spirit in Saint John, who is said to have witnessed frightening visions of the cataclysmic events leading up to Christ’s Second Coming and recorded them in a text known as the Apocalypse (or the Book of Revelation in the Bible).

The illuminator of the Getty Apocalypse (so called because it resides in our collection) depicts these horrific and puzzling visions within cinematic frames. We find Saint John himself viewing many of the events through windows or small openings (that’s him at the top right and bottom left, looking through a peephole). In other pages of the book, he’s present within the visionary landscape, a participant in his own nightmares.

This book is suited for Bran because his visions are often as perplexing as those of Saint John. This Apocalypse might provide him with insight into how to interpret portents of future events. Bonus: this edition features a commentary written in red ink for a quick reference and easy interpretation guide.

Daenerys of the House Targaryen, the First of Her Name

Mother of Dragons, The Queen Across the Sea, Khaleesi

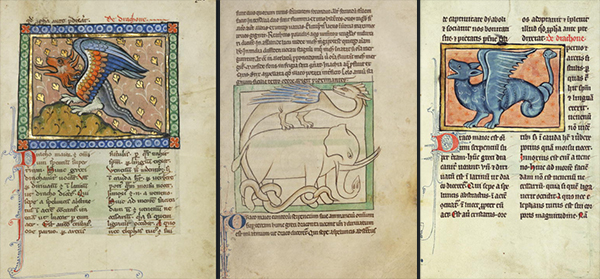

Left: A Dragon in a Bestiary, Franco-Flemish, Thérouanne?, about 1270. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 ½ x 5 5/8 in. (19.1 x 14.3 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3, fol. 89. Center: A Dragon in the Northumberland Bestiary, England, about 1250–60. Pen-and-ink drawings tinted with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 ¼ x 6 3/16 in. (21 x 15.7 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 54. Right: A Winged Dragon in Hugo of Fouilloy and William of Conches, Bestiary, Franco-Flemish, Thérouanne?, fourth quarter of the 13th century (after 1277). Tempera colors, pen and ink, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 9 3/16 x 6 7/16 in. (23.3 x 16.4 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 4, fol. 94

Who She Is

One of many claimants to the coveted Iron Throne, the seat of kings, Daenerys Targaryen comes from an ancient family whose true rulers are rumored to be unscathed by dragon fire. Exiled from her homeland and married to the leader of a brutish and nomadic race, Daenerys is a force to be reckoned with: the self-appointed Mother of Dragons nurtures three airborne monsters and is gathering an army of supporters to aid in her ascent to or seizure of the seat of power.

What She Needs to Read

What better book for a woman unscathed by dragon fire than a book about them? Part natural history, part moralizing tale, the bestiary contains descriptions about and lessons learned from all types of known living creatures, and even some unknown. Among these beasts is the dragon, described as the largest and most fearsome of all earth’s creatures, from either the lands of Ethiopia or India (medieval readers were a little sketchy on their geography), and the enemy of elephants (which dragons purportedly strangle with their tails).

Dragons abound in the margins and historiated initials of a variety of medieval manuscripts, and I’m tempted to christen the ones in the three pages above by the names of Daenerys’s three dragons: Drogon, Rhaegal, and Viserion.

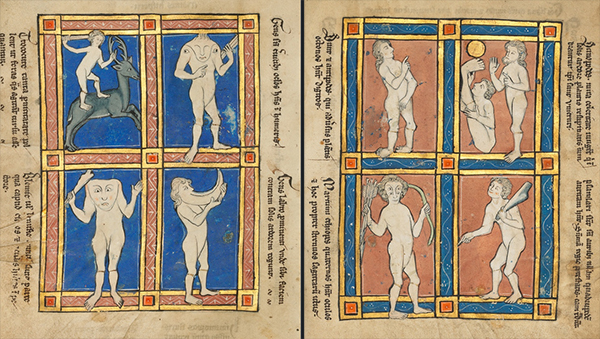

As an aside, one of our bestiaries includes a section dedicated to images of strange men and women of distant and foreign lands. No doubt if they had existed, even in rumor, the Dothraki—a nomadic people at times allied with Daenerys as a result of her marriage (mentioned above)—would have received a mention from medieval writers.

Trococie, A Headless Man with Eyes on His Shoulders, A Headless Man with a Face on His Chest, a Man with a Large Upper Lip; Antipode, Scinopode, Coastal Ethiopian, Psalmlarus, from Hugo of Fouilloy and William of Conches, Bestiary, Franco-Flemish, Thérouanne?, fourth quarter of the 13th century (after 1277). Tempera colors, pen and ink, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 9 3/16 x 6 7/16 in. (23.3 x 16.4 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 4, fols. 117v–118

Joffrey of the Houses Baratheon and Lannister, the First of His Name

King of the Andals, the Rhoynar, and the First Men, Lord of the Seven Kingdoms, Protector of the Realm

Initial N: James I of Aragon Overseeing a Court of Law (detail) in Vidal de Canellas, Michael Lupi de Çandiu, and Michael Lupi de Çandiu, Feudal Customs of Aragon. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 14 3/8 x 9 7/16 in. (36.5 x 24 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 6, fol. 1

Who He Is

Remember that incestuous relationship I referred to earlier, the one that Bran witnessed? Well, Joffrey Baratheon is the offspring an earlier tryst between the same twin brother and sister, Jaime and Cersei Lannister (more on her below). He is foul, pernicious, juvenile, sadistic, and overly entitled. These attributes are exacerbated when the teenager becomes king.

What He Needs to Read

Perhaps a manual on legal customs like the Feudal Customs of Aragon would suit our too-spoiled-to-rule king. The text contains the newly established law code proclaimed by King James I of Aragon and Catalonia (Spain) in the 13th century. Some of the laws might strike contemporary readers as frivolous or harsh, which is often the reaction I have to Joffrey’s approach to kingship. If nothing else, the splendid images of kings enthroned in power over courtiers, criminals, and the condemned would surely excite young Joffrey. Browse more images and learn the content of some of the laws here (for example, one law decreed that if a woman left her husband, he had the legal right to take back both her and his possessions).

Cersei of the House Lannister

Queen Regent and Lady of Casterly Rock

Who She Is

Mother, sister, lover (and sister-lover), daughter, and queen regent…that about sums up Cersei Lannister. Haunted by prophecies about life, marriage, children, and death revealed during her childhood, she keeps a close network of spies, has some daddy issues to deal with, and embodies cunning and beauty.

What She Needs to Read

The above description applies not only Cersei, but also to many of the historical characters featured in Laurent de Premierfait’s translation of Boccaccio’s The Fates of Illustrious Men and Women.

Clockwise from top left: Athaliah, Queen of Judah, Dragged from the Temple; The Death of Brunhilde, Queen of France; The Suicide of Queen Dido; The Suicide of Lucretia; Virginia Killed by Her Father to Save Her From the Attentions of Appius Claudius; Nero Pauses for a Drink During the Mutilation of His Mother’s Body in Boccaccio, The Fates of Illustrious Men and Women (translated into French by Laurent de Premierfait), Boucicaut Master, about 1415. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 16 9/16 x 11 5/8 in. (42 x 29.6 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 63, fols. 39, 282, 41, 68, 83, 224

The women we see above (clockwise from top left) perpetrated, or were victims of, vivid horrors:

- Athaliah, Queen of Judah, attained the throne by murdering all other royal offspring and was later hauled off by her hair and murdered

- Brunhilde, mother of Clotaire III, king of France, was tied to a horse’s tail, dragged, and drawn and quartered for crimes she did not commit

- Dido and Lucretia committed suicide

- Virginia was murdered to save her from the advances of a lecherous suitor

- The body of Nero’s mother and incestuous love partner Agrippina, was morbidly and savagely mutilated after her death

Boccaccio’s text would probably disturb Queen Cersei, who has prophetic dreams, faces a few narrow escapes from death, at times has a tenuous relationship with her son Joffrey, and carries on an incestuous relationship with her brother, Jaime.

Tyrion of the House Lannister

Master of Coin and former Acting Hand of the King

Who He Is

A man of shifting fortunes and alliances, Tyrion Lannister is Cersei’s younger brother, the so-called dwarf or Halfman. Despite his stature and the fact that he is at times despised by members of his own family and at others used as a pawn or prisoner, Tyrion carefully balances shrewdness, wit, and savvy calculation.

What He Should Read

Tyrion would benefit from a close reading of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (which in a way is a medieval prequel to Game of Thrones). An account of the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), the text and its images of conquest, courtly embassies, the fall of cities, royal assassinations, and naval battles would likely appeal to an individual who has proven to be quite strategic in the courtly chess-like game of fate as well as in intense, all-out, close-call military clashes. The King of Cyprus, shown below being murdered by his brothers, could have learned a thing or two from Tryion Lannister about self-preservation.

The King of Cyprus Killed by His Brothers in Jean Froissart, Chronicles (Book Three), Master of the Getty Froissart, 1480–83. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment, 18 7/8 x 13 ¾ in. (48 x 35 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 7, fol. 80

The artists of each of the above illuminations captured the essence of the Middle Ages in Europe through quotidian details of life, court atmosphere, and historical circumstances, all of which come to life in vivid hues, cinematic compositions, and dramatic actions.

For more medieval fun with Game of Thrones, see our weekly episode-inspired posts on the Getty Tumblr, coming every Monday. We promise no spoilers.

This was so clever. A fun, entertaining read. Thanks!

Well done Bryan. I really enjoyed reading this following the GoT marathon and season 4 premiere this past weekend. It certainly does stir interest in the medieval manuscripts here at the Getty!

Masterful job, indeed. This is the kind of thing that makes visiting the Getty an adventure. So well connected to actual pieces. Makes you wonder if what your are looking at has a story, series, or movie in its history. Great job!