A family visiting the Getty Villa explores ancient art, history, and mythology through frescoes from the ancient Roman city of Herculaneum.

Teaching kids about the world of ancient Greece and Rome presents a few problems for parents. The history and mythology of the classical world can be strong stuff for kids. Yet there’s no denying that the ancient world can also hold a great fascination for them. As education specialist for family programs at the Villa, I encounter 8-, 7-, even 6-year-olds who are completely captivated by the heroes, gods, and monsters that populate the tales of classical myth and history. The adventure and derring-do of these stories is an easy sell to kids, and parents too for that matter. But I believe your kids need to know more than that.

Sooner Than You Think

Even if it will be years before your children encounter James Joyce and need to know who Ulysses is, how long will it be until they read Harry Potter (if they haven’t already)? Greek myths may seem at first glance to be so ancient as to be disconnected from modern times, but the history of the classical world still underlies so much of our culture that not to know about it can mean missing a lot. A character like Firenze, the centaur who becomes a teacher at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, harkens back to the tutor of heroes, the classical centaur Chiron. This is but one example of the enormous collection of knowledge embodied in classical mythology that authors and artists return to again and again.

Many kids of today are finding entry to classical myths via the books of Rick Riordan—the Percy Jackson and Heroes of Olympus series. They’re fun, light entertainment that has some clever updates of classical mythology. My personal favorite is the Lotus casino in The Lightning Thief, a modern-day spin on the episode from Homer’s Odyssey in which the hero gets caught in the land of the Lotus eaters. It’s also a fairly good warning on the dangers of losing oneself in intoxication—always a nice lesson to share with your kids. Common Sense Media (my go-to spot for judging what media is appropriate for what age of kids) rates the Percy Jackson books as for kids aged 9–10. I’d probably pull that down a year to ages 8–9, but either way much is lost in reading those books if you don’t know the myths they are referencing.

Confronting the Dark Side

But about those problems you were mentioning…

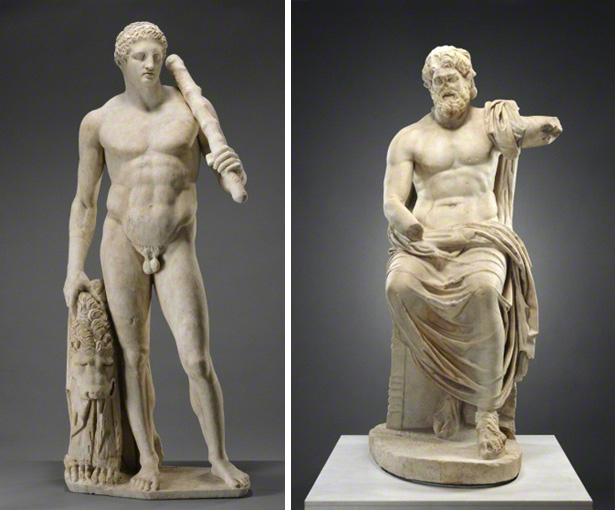

Percy Jackson is all well and good, but those stories don’t deal much with the darker aspects of the classical world. Greek mythology contains stories where war, rape, cannibalism, and incest are fairly common (and except for the cannibalism, ancient history includes a lot of the same). How do you introduce a 7- or 8-year-old to these themes without scarring them for life? To ease children in, start with the art. Truly, for the youngsters, an encounter with a 6-foot-tall statue of Herakles or his dad, Zeus, makes a lasting impression.

The Landsdowne Herakles and the Marbury Zeus are entries into ancient history and mythology your kids aren’t likely to forget. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 70.AA.109 and 73.AA.32)

But, the art alone does little—the stories are key for kids. The classic of mythology for children is D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths. I can’t recommend it highly enough (and neither can the over 200 reviewers on Amazon). It tells the stories of classical mythology in a straightforward style that neither whitewashes nor dwells on the more gruesome aspects. It also accompanies each story with kid-friendly illustrations that help take the bite out of what might otherwise leave nightmarish images in the mind of a young reader. Read this book on top of a few encounters with authentic ancient art, and you’ve held your child’s hand as he or she steps into a deep pool for the first time.

Modern Meanings

The real reward comes later, though. I just finished reading The Hunger Games trilogy by Suzanne Collins, a series kids are likely to encounter in middle or high school. This controversial young adult series demonstrates how knowledge of the classical world and its formative myths is still vitally important. The tale combines the idea of the brutality of ancient power plays with the brutality of modern reality TV. The Hunger Games is wildly popular with the young teen set; the first film adaptation, released this past summer and just now entering homes via DVD and instant streaming, made close to $700 million. What’s perhaps surprising about this number is that The Hunger Games is a scary, scary story. Understanding the mythological background of it lends context and depth—things a story like this desperately needs for a young reader to get its full meaning.

Theseus defeats the monstrous Minotaur in this 2,400-year-old Attic black-figure amphora. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AE.376)

Collins cites the myth of Theseus as a major inspiration for the series. Theseus was the prince of Athens who returns to his home city at a bad moment, the year of the Tributes. Seven youths and seven maidens are being chosen from Athens to be sent to the powerful sea-kingdom of Crete, where they will be sacrificed to the horrible monster, the Minotaur. Accounts vary as to why the Tributes must go, but in one version Crete has defeated Athens in a war and demanded the Tributes as evidence of Athens’ submission. It’s this idea that Collins uses in The Hunger Games. The story takes place after environmental disaster has caused the fall of Western civilization. In the ruins of the United States, a war among the survivors has led to the suppression of 13 Districts by the Capitol. As a reminder of their defeat, once a year each District must provide a female and a male Tribute between the ages of 12 and 18 to fight to the death in the Hunger Games, which are broadcast live—a source of melodramatic entertainment in the Capitol, and of vicious oppression in the Districts.

The Hunger Games deals out its child-on-child violence and the political implications of such without too much gore, but with plenty of horror. The Capitol is largely modeled on our worst ideas of the worst of ancient Roman society. The denizens of the Capitol sport names like Seneca and Plutarch, and the nation of the book is named Panem, a reference to Panem et Circenses, the Latin phrase coined by Juvenal, a Roman poet. Juvenal was decrying the Roman population’s abandonment of civic values and responsibilities in exchange for government-provided appeasement and base entertainment (bread and circuses). The books likewise take on issues of the use of propaganda, treating deeply with how celebrity can victimize both the viewer and the viewed, and how masses of people can be oppressed or inspired by manipulative art—something at which the Romans were expert.

Head of Emperor Augustus and Coin with Head of Augustus: Born Octavian, the first emperor of Rome was never called emperor, only First Citizen, and his birth name was supplanted by the one meaning “great” or “venerable.” Statues and coins like these spread an image of Augustus as calm, strong, and measured—examples of early political propaganda that still influence how politicians portray themselves today. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 78.AA.261 and 80.NH.152.133)

When I began the books, I had trouble suspending my disbelief at how cavalierly the Capitol citizens enjoyed watching children murder each other. Then I began to review my history—not just of the ancient Mediterranean, but the world in general, even up to today, when child soldiers still face each other on battlefields. Yes, humanity can be that callous and brutal. Part of the point the books make for young adults today is how fine a line there is between civilization and barbarism, and it has nothing to do with sophistication—in the books it is the erudite citizens of the Capitol who are the barbarians. Lacking that knowledge of ancient history, however, the books might come off as merely remote imaginings that could never happen in reality.

Mosaic with boxers: A scene from the Aenied in which two boxers fight to a bloody end for the watching crowd. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 71.AH.106)

I found The Hunger Games fascinating and thought-provoking, though some commentators have questioned their appropriateness for young people. The books’ mix of ancient and modern ideas created a powerful story with compelling characters. They provide any family, group of teen friends, or classroom with numerous ideas to discuss and explore. Without that discussion, without an understanding of the ancient culture which informs both the books and our own modern life, not only is a lot of the potential meaning of the stories lost, but so is much of the potential meaning of our own day-to-day world.

Exploring Mythology at the Getty Museum

If you’re interested in introducing your kids to the ancient world, here’s a few works of art in the Getty Museum’s collection to get you started.

At the Getty Villa:

Storage Jar with Herakles Attacking a Centaur—In ancient mythology, centaurs are wild beasts more likely to carry off your wife than teach you valuable knowledge.

Statuette of Poseidon—A 2,000-year-old bronze sculpture of the god of the sea, Poseidon, who Rick Riordan makes the father of his young demigod hero, Percy Jackson.

Jug with Man and Bull—The influence of ancient Cretan culture can be seen on this small jug.

Gladiator—This small statuette depicts a gladiator striding into combat. These men were usually slaves or criminals put into the arena to fight for the entertainment of the Roman crowd.

At the Getty Center:

Ulysses at the Palace of Circe—A vivid episode from Homer’s Odyssey.

The Banquet of Cleopatra—Depictions of Cleopatra in art have tended to be influenced by Roman author Plutarch’s unflattering description of her as decadent, as we see here.

When I read the Hunger Games, I also thought the child-on-child violence a bit much. But this kind of violence isn’t just a real thing from the history books. I realized that we watch this kind of violence today in the form of sports like pro football and boxing. Remember the controversy in pro football this past year in which players were given rewards for “taking out” players on the other team? Echoes of the Hunger Games in our midst…

My 8 year old son has trouble being alone at night after learning of monsters etc through school.

You ask “How do you introduce a 7- or 8-year-old to these themes (war, rape, cannibalism, and incest ) without scarring them for life?” – maybe you can’t, and i don’t think their lives are improved or enriched in any way by introducing these things at all. Many people experience rape and incest first hand, and it isn’t positive. Humans are adaptable, and can adapt to the fact that life sucks at anytime, so why not put that off as late as possible?