Untitled (Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, The Vexed Man, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA), 2008, Ken Gonzales-Day. Chromogenic print. Ken Gonzales-Day and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. © Ken Gonzales-Day

What do the expressions “highbrow” and “lowbrow” have in common with saying a woman has “mousey” features? What does Homer Simpson have to do with photographs of sculpture in profile by contemporary artist Ken Gonzales-Day? All are contemporary manifestations of an ancient pseudoscience that permeated visual culture in European history, notably in the 18th and 19th centuries: physiognomy.

In Messerschmidt and Modernity at the Getty Center, there’s a fascinating case of four books dating from 16th through the 19th centuries related to this magical pseudoscience, which assesses character and morality from outer appearance, applying the practice of “judging a book by its cover” to the human form.

Physiognomy has its roots in antiquity. As early as 500 B.C., Pythagoras was accepting or rejecting students based on how gifted they looked. Aristotle wrote that large-headed people were mean, those with small faces were steadfast, broad faces reflected stupidity, and round faces signaled courage.

David Brafman, rare books curator at the Getty Research Institute, told me that physiognomy—from the ancient Greek, gnomos (character) and physis (nature), hence “the character of one’s nature”—really became popular again in 16th-century Europe, as physicians, philosophers, and scientists searched for tangible, external clues to internal temperaments.

In the early 1600s, Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta, considered the father of physiognomy, was instrumental in spreading ideas about character and appearance in Europe. Della Porta came up with the idea for physiognomy through his alchemical experiments, in which he attempted to boil down and distill from substances their “tincture,” or pure essence. He made an analogy to the human essence, suggesting that one could deduce an individual’s character from empirical observation of his physical features. His widely disseminated book on the subject, De humana physiognomia, was instrumental in spreading physiognomy throughout Europe. Illustrations in the book depict human and animal heads side by side, implying that people who look like particular animals have those creatures’ traits.

Leonine specimens: Illustration in Giambattista della Porta’s De humana physiognomia (Naples, 1602). The Getty Research Institute, 2934-552

Images like these were powerful, and illustrations, sculptures, drawings, and other visual forms were key to the spread of physiognomy and its strange ideas.

In the second half of the 18th century, Johann Caspar Lavater became the new king of physiognomy. He blended an examination of silhouette, the profile, portraiture, and proportions into his best-selling book, Essays on Physiognomy, which included a detailed reading of the face broken down into its major pieces, including the eyes, brows, mouth, and nose. The expression “stuck-up” comes from this time, when a person with a nose bending slightly upwards was read as having a contemptuous, superior attitude.

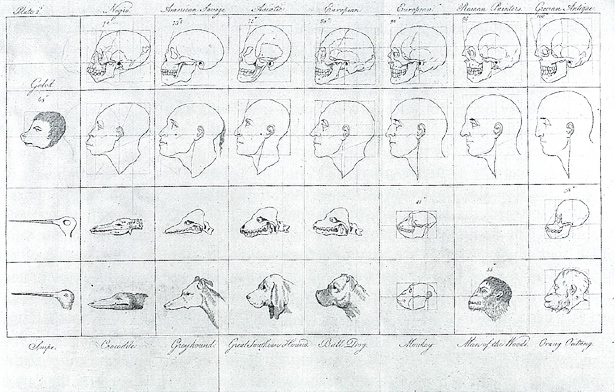

Representative plates from Johann Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy of “problematic” profiles and facial structures

Lavater often expressed an obvious cultural bias in his readings of the morality of people from other countries. “Lavater idealizes the familiar and praises what he knows,” wrote one critic, “but finds ‘deficiencies’ in the faces of Africans, Laplanders, and Calmuck Tartars.”

The connections between physiognomy and aesthetics were pointed in Essays on Physiognomy, as Lavater commissioned artist Johann Henrich Fuseli and poet William Blake to provide the illustrations. This artistic interest in physical appearance and character contributed to the development of theories of the ideal geometric proportions of the face in the late 18th century by theorists such as William Hogarth and Lord Shaftesbury.

Diagram of facial angles from Charles White, An account of the regular gradation in man, and in different animals and vegetables; and from the former to the latter. Illustrated with engravings adapted to the subject (London, C. Dilly, 1799). This item is reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Rare Books, 302625

The influence of physiognomy can be seen throughout 18th- and 19th-century European art. In the 18th century in particular, natural philosophers embraced the “ideal” features found in classical sculpture, which were mistakenly thought to represent how the ancients actually looked. The assumed cultural superiority of ancient Greece became attached to these features, which were adopted by European artists and depicted again and again. “Others”—such as Asians and Africans—were less not only less beautiful, but less moral.

Like man, like swine: Illustration in Giambattista della Porta’s De humana physiognomia (Naples, 1602). The Getty Research Institute, 2934-552

Photographer Ken Gonzales-Day examined this phenomenon in his series Profiled, an example of which is on view in Messerschmidt and Modernity. He created photographs of portrait sculptures in museum collections, both to explore the tradition of portraiture in Western art and to critique the pictorial conventions and racial profiling advanced by Lavater—who believed the profile to be the best perspective to analyze human character.

Untitled (Henry Weekes, Bust of an African Woman, based on a photographic image of Mary Seacole, and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Bust of Mm. Adélaïde Julie Mirleau de Neuville, neé Garnier d’Isle. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA), 2011, Ken Gonzales-Day. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of and © Ken Gonzales-Day and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

Today, scholars are still studying the science of faces and how different traits, features, and expressions affect us. For example, it’s well established that faces with rounded contours attract us, because they signal childlikeness and evoke parental instincts. We even have a tendency to view “baby-faced” people as less likely to commit premeditated crimes. Unfortunately, if you’ve got an angular face, you’re probably a criminal.

So even though the term “physiognomy” no longer resonates, the assumption of physical appearance as moral indicator lives on. Homer Simpson must be ugly, because he is stupid. When Dorothy asks the good “white” witch in The Wizard of Oz why she’s so beautiful, she replies, “Why, only bad witches are ugly.” Though our consumer-driven world has increasingly substituted clothing and material possessions as signifiers of character, we continue to label our fellow humans as “thick-headed,” and people get stopped on the street because they “look suspicious.”

Physiognomy is uncomfortable, messy, and often racist, but I do understand its motivation. The urge to classify, study, and categorize people is based in the desire to understand ourselves more clearly. But for every ideal form, there’s an “other” who also wants to explore herself on her own terms, without being profiled.

Fascinating. Are Ken’s works available ?

Hi Trent! Apologies for the late response. If you haven’t already hunted around, here is a link to Ken’s website! He’s got some images, texts and links on his site if you’re interested in seeing more what he’s about as an artist: http://www.kengonzalesday.com/

Physiognomy is not a pseudosciense. There is a strong correlation between attractiveness and intelligence. Because what is “attractiveness” — it is simply an aesthetic judgment of the fitness of the Race. The outward reflects the mental capacity in the majority of cases. If we do not quantify the values that we desire as a society and work to ensure the propagation of them, through our now aesthetically ignorant brainwashing those special genetic specimens will be bred out of existence.