Whether he planted his tripod in India, China, Japan, Korea, or Burma, the Italian-born photographer Felice Beato always portrayed a country’s culture through a distinctly Western lens. The Museum’s current exhibition of his work, Felice Beato: A Photographer on the Eastern Road—now entering its final weeks—shows how this prolific chronicler of vast territories captured the tumult and traditions of the East for a Western audience.

Interior of the Sikh Temple with Marble Mosaic, Felice Beato (British, born Italy, 1832–1909), negative, 1858; print 1862. Printed by Henry Hering. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.475.7

As British colonial empires expanded in the second half of the 19th century, Westerners’ fascination with far-away lands seemed boundless. Traveling with British military officers, Beato was eager to take advantage of this growing market of would-be adventurers. Armchair travelers poured over Beato’s exotic images, which were widely published in magazines, military memoirs, and travel diaries.

What did they see? A sampling of wonders: A magnificent mosque in Constantinople. A samurai and a tattooed Japanese groom. The entrance to the Taj Mahal and Chinese shops on a Canton street.

Treasury Street, Canton, Felice Beato, negative, April 1860; print 1862. Printed by Henry Hering. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.26.198.69

Beato was a talented technician, said Anne Lacoste, the show’s curator, who picked 130 works from 1,100 photographs in the collection. He captured sweeping panoramas as easily as architectural studies or intimate portraits.

Beato and his contemporaries used traveling darkrooms—horse-pulled carriages with tents, large-view cameras, and special tripod mounts. On his expeditions, Beato often used albumen glass-plate negatives, which could be prepared in advance. That approach is useful, it turns out, in risky situations.

Beato endured many dangers as he recorded wars, skirmishes, and sackings: The Crimean War, the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, the Second Opium War, and the American expedition to Korea. “Beato documented dramatic changes and cultures,” Anne told me. “But it wasn’t just an artistic endeavor, it was about trying to transcribe his own experience.”

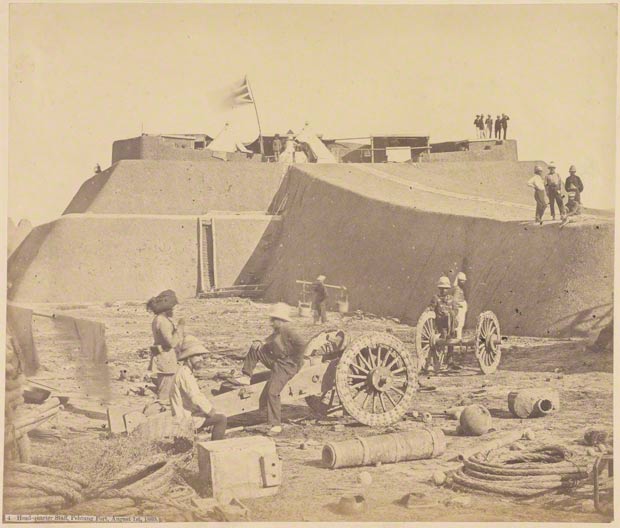

In Headquarter Staff, Pehtang Fort, British soldiers are portrayed after a battle of the Opium War of 1860, in which Britain fought Chinese efforts to block opium imports from India. The British officers, surrounded by military paraphernalia, are perched on top of the fort above a water-carrying cart, looking victorious. In contrast, Top of the Wall of Peking captures a local Chinese man crouching on the side of the road, dwarfed by a nearly identical cart.

Headquarter Staff, Pehtang Fort, Felice Beato, August 1, 1860. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.473.27

Top of the Wall of Peking, Felice Beato, October 14, 1860, or later. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XA.886.5.27

“This is a completely different way of representing the same object with the westerner and the local,” Anne noted. “It shows how subjective photography can be when you are getting a story through images.”

Beato also put his personal stamp on his photographs from India’s first War of Independence, in which the British military brutally suppressed the colonial rebellion. Knowing there was a great appetite for images of the war, Beato delivered. His shocking photograph Interior of the Secundrabagh after the Slaughter of 2,000 Rebels documented the carnage. It’s believed to be among the first photographs of corpses on a battlefield. But the scene was a re-creation. Beato had disinterred bones and arranged them on the site for dramatic effect. There were also no dead Westerners—which would have offended Victorian sensibilities.

Interior of the Secundrabagh after the Slaughter of 2,000 Rebels, Felice Beato, 1858. Partial Gift from the Wilson Centre for Photography. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.26.208.7

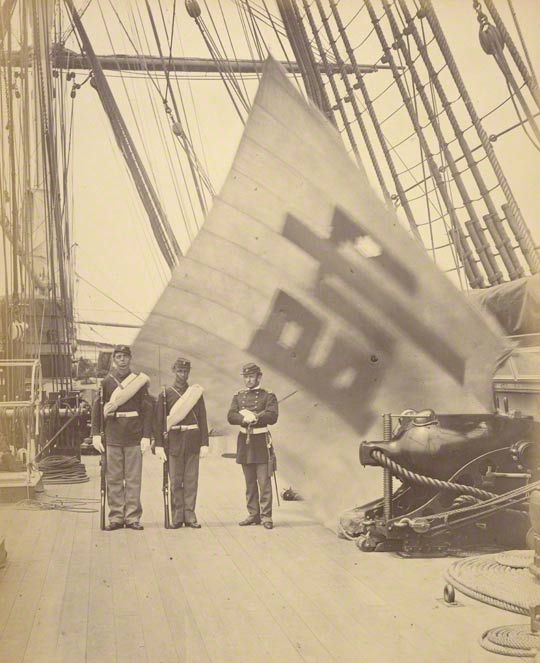

Another example of such spin is The Flag of the Commander in Chief of the Korean Forces. The photograph, taken on a ship, shows proud American officers standing on deck in front of the white flag of Korea, puffed out like a sail. The American military campaign in Korea was failing, but the photograph projects the illusion of victory.

The Flag of the Commander in Chief of the Korean Forces, Felice Beato, June 1871. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.26.199.46

Once Beato arrived in Japan in 1863, he turned his eye to the profitable venture of introducing Japanese culture to the West. He spent time in studios and outdoors depicting such things as street scenes, mail carriers, and ladies modeling traditional fashions.

To get more detail in the pictures, Beato used wet-plate collodion negatives, whose glass is coated with light-sensitive silver salts. The exposure often took about 10 or 15 seconds, so even breathing could soften the image. Beato would coach his subjects to sit still—something he himself could rarely do.

Samurai with Long Bow, Felice Beato, 1863. Partial Gift from the Wilson Centre for Photography. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.26.154

While examining these vivid, early photo images, I couldn’t help noticing that what you describe as ‘water carts’ look definitely like Chinese muzzle-loading cannon to my eye. There is a water-carrier (presumably) bearing twin buckets on a pole in the background of the ‘Staff’ photo. Some confusion perhaps?

WBW