It’s well after midnight, and Getty Conservation Institute scientists are still at work—not in Los Angeles, but at a synchrotron radiation source far from home.

Late night at the Synchrotron Research Center in Stoughton, WI.

To explain why, I need to provide a little background. A synchrotron is a particle accelerator that moves electrons in a controlled fashion at very high speed to produce super-bright light containing a broad range of energies. The electrons are held in a giant storage ring, making the energy available over a long period of time. Scientists can use portions of light at the exact energies they need to perform specific scientific experiments. There are currently about 70 synchrotron facilities worldwide, including half a dozen in the United States.

Synchrotrons are becoming valuable tools for studying the composition of cultural objects, such as works of art. The use of synchrotron facilities for cultural heritage science is expanding rapidly, and some facilities even have beamlines (individual workstations) that are specifically designed for use by cultural heritage scientists, such as the Ipanema platform at the Soleil Synchrotron in France. Most experiments related to cultural heritage, however, are conducted at synchrotrons without dedicated beamlines and are performed on small samples removed from works of art.

An end station at Stanford University/Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource

The Conservation Institute’s ongoing research currently uses two different synchrotron sources. The Athenian Pottery Project uses cutting-edge technologies at the Stanford University/Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource to image tiny samples from pottery sherds at sub-micron length scales (1/100th the width of a human hair) to better understand how the shiny black gloss characteristic of ancient Athenian pottery was created.

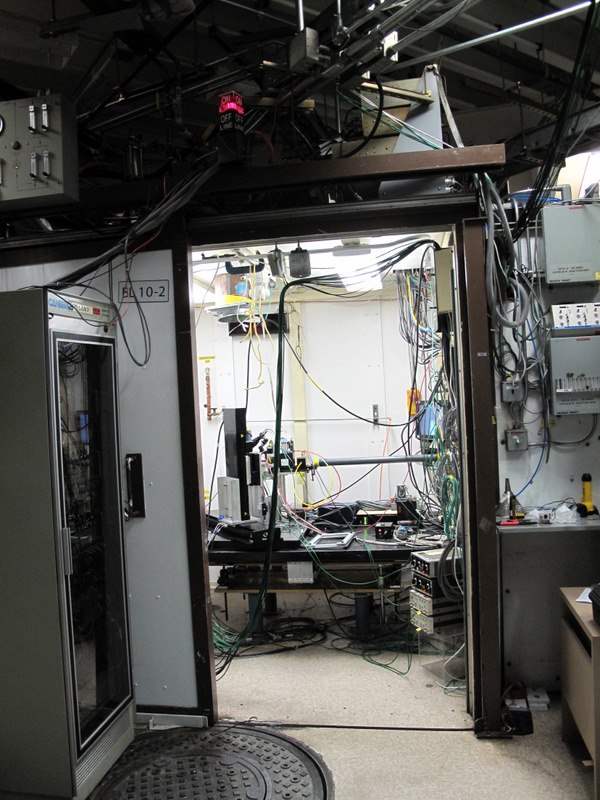

We are also working to improve our understanding of materials used to create paintings, including multiple thin layers of pigments and organic binders and glazes. To do this we are examining tiny paint samples prepared as cross-sections using the IRENI Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) beamline at the Synchrotron Radiation Center in Stoughton, Wisconsin. This unique FTIR beamline can create chemical images of layers within cross-sections faster and often with higher resolution than can be accomplished using a laboratory-based system, helping us identify the materials present.

Working at a synchrotron facility can be very different from working in our typical laboratory setting. For one thing, the sheer size of the storage rings at synchrotron facilities means that the buildings in which we conduct experiments are comparable in size to airplane hangars. Often, no carefully climate-controlled museum spaces exist, which is why only small samples from works of art typically make the journey with us for analysis.

Panoramic view of the Aladdin storage ring at the Synchrotron Research Center in Stoughton, WI.

The amount of time available at a synchrotron facility to any single researcher is limited, and is usually scheduled in 24-hour blocks. Working from 9 am until 2 or 3 am the following day can be the norm, and teams of people often work together so that experiments can continue around the clock This also means that during one visit to the beamline, we can collect enormous amounts of data which can take many months to work through.

Although working at a synchrotron facility can sometimes feel like you’ve entered a futuristic sci-fi world, there are definite, and sometimes unexpected, benefits. In particular, the work the Conservation Institute has done at Stanford and the University of Wisconsin has introduced us to a new set of colleagues and partners—beamline scientists and the synchrotron research community.

The IRENI endstation at the Synchrotron Research Center

Our interactions with these new partners continually expands the way we think about our own work in conservation science. In return, our presence increases awareness within the wider scientific research community of the challenges presented by cultural heritage samples. The intensity of working at the synchrotron also gives us a chance to focus deeply on individual projects, and on the nuanced analyses that may lead to new discoveries. And, after all, it’s those new discoveries—and the impact they may have on our understanding of our cultural patrimony—that make it worth working through the night.

Sunrise after a long night of experiments.

Comments on this post are now closed.