A cultural crossroads since ancient times, Sicily took on a truly international character in the Middle Ages

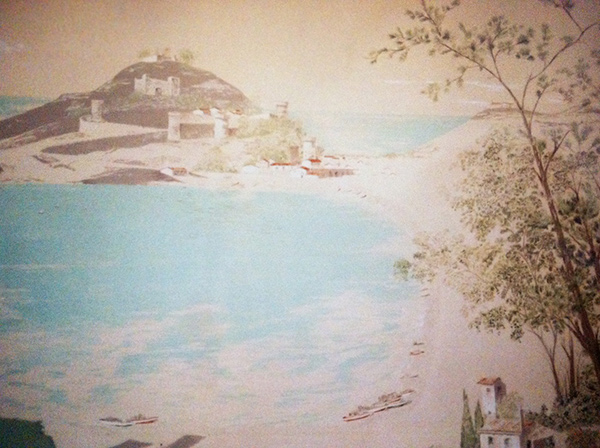

Bay of Palermo, Sicily, 1963, Samuel J. Magnolia. Mural painting, about 8 1/2 x 15 ft. Photo courtesy of Rosemarie Anne Keene

My interest in art history began in Sicily, the island at the crossroads of the Mediterranean. This Italian island has always held a special place in my heart because it was the childhood home of my grandfather. As a young boy in California, I remember him trying to teach me how to draw—often near a mural he painted showing the Bay of Palermo (above)—and so I owe my professional path as an art historian to Sicily, by way of my grandfather. No surprise then that, as an undergraduate art history student, I wrote my first term paper on the architecture and mosaics from the Norman period at the Cathedral of Monreale in Sicily.

For the past several months, Sicily has often been on my mind thanks to the exquisite exhibition at the Getty Villa, Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome, closing this Monday, August 19. The exhibition spans the fifth to the third centuries B.C., a period rich in contact with Greece and later Rome, but also one in which Sicily was a major center of cultural and artistic innovation in its own right. The exhibition’s theme of innovation reminds me of another moment in Sicily’s history, that of the late 12th through the early 14th centuries, when art produced in cities such as Palermo exhibited features reminiscent of the iconography, format, and decoration found in objects produced by Byzantine, Southern Italian, and Norman craftsmen.

The Manuscripts Department at the Getty Museum is fortunate to have two masterpieces of Sicilian illumination from this later period: a Bible and two miniatures from an Old Testament manuscript. A lot happened between the fall of Sicily to the Romans in the third century B.C. (which marks the end of the Sicily exhibition at the Villa) and the creation of these illuminations, so a little bit of context is necessary to fully appreciate their innovations.

Understanding the history of kingship and rule in medieval Sicily is akin to keeping up with all of the players and kingdoms in Game of Thrones, but this constant dynastic change contributed directly to the island’s rich artistic heritage. While the Roman Empire was disintegrating in the 5th century A.D., a wave of invasions swept across Sicily, with the Vandals, followed by the Goths, the Ostrogoths, and finally the Byzantine armies of Emperor Justinian I (in the 6th century A.D.). Byzantine rule lasted until the 9th century with the Muslim conquest of the island, which began the Emirate of Sicily. In the 12th century we encounter the Normans, a people from Northern France who ruled the island and portions of Southern Italy (and England) until the end of the century. For the next few hundred years, Sicily in turn was ruled by the Germanic Hohenstaufen dynasty, then the Angevins (from around the Loire Valley in France), and then by the Aragonese (of Spain).

And what does all this political history have to do with the art produced in the late 12th, 13th, and early 14th centuries? Let’s find out.

The Crucifixion and the Harrowing of Hell in a New Testament, Sicilian, late 1100s. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 9 11/16 x 6 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 5, fol. 191v

The Getty’s Sicilian Bible is dated around 1200. The composition of The Crucifixion shown above is similar to the same scene found in a late-11th or early-12th-century Missal from Foligno, Italy, today in The Morgan Library & Museum (MS M.379, fol. 6v). Both of these miniatures are representative of the Italian Romanesque painting style, but the Sicilian Bible also exhibits the characteristic gold background associated with Byzantine painting of the time. Scholars have noted that the format of the page—including the foliate designs and the red, white, and green dog-tooth pattern—are similar to those found in Norman and early Parisian architecture and illumination. The dog-tooth architectural framing around the miniature finds its counterpart in Norman ecclesiastical structures at sites like the Cathedral in Durham, England (one of the finest examples of Norman architecture in England) or the cloister of the Cathedral of Monreale. Additionally, the similarities in page layout can be seen in the mid-13th century Parisian Psalter from the Getty seen below, as well as in an English Psalter from the Morgan Library (MS G.25, about 122), which also provides an example of similar foliate motifs. Thus, this early-13th-century Bible exhibits myriad art historical influences and precedents, a beautiful portrait of an international artist community.

Initial B: David Playing the Harp and David and Goliath in the Wenceslaus Psalter, French, about 1250–60. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 9/16 x 5 ¼ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig VIII 4, fol. 28v

Moving forward in time to the early 1300s, the two Sicilian manuscript cuttings in the Museum’s collection, both of which show Old Testament scenes, may have been part of a profusely illuminated Bible like those being produced in Naples at that time. This idea was recently proposed by art historian Rebecca W. Corrie, who also convincingly suggests that both scenes associate the Assyrians and Persians in the Biblical narratives with the contemporary Islamic rulers of Jerusalem, a common trope in art and political discourse at that time. This association would have appealed to the Aragonese ruler Frederick III, for whom similar images were commissioned at that moment.

Two other cuttings from the same manuscript survive (in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, and the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), and both directly copy the architecture and iconography found in the 12th-century nave mosaics of the Cathedral of Monreale. Therefore, we have here an example of Byzantinizing (yes, it’s a real word) illumination, with potential Christian-Islamic dialectical undertones, created during the Aragonese rule in Sicily. If the original manuscript had survived in its entirety, it would no doubt have been a remarkable sight—and we would certainly have been impressed by its visual variety and international character.

The Death of Sennacherib from an Old Testament, Sicilian, about 1300. Tempera colors and gold on parchment, 2 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum Ms. 35, leaf 1

The Vision of Zechariah from an Old Testament, Sicilian, about 1300. Tempera colors and gold on parchment, 2 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum Ms. 35, leaf 2

With the Sicily exhibition coming to a close at the Villa, I continue to think fondly about the island’s vast history and its unique international artistic heritage. As a manuscripts specialist, I am happy that the exhibition has allowed me to return to Sicily for inspiration across the centuries.

I thank Kristen Collins for her thoughts and feedback on this post.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Corrie, Rebecca W. “Sicilian Ambitions Renewed: Illuminated Manuscripts and Crusading Iconography.” Studies in Iconography 34 (2013), pp. 77–79, 82, 84, 88–89, 91-93, figs. 20–21.

Evans, Helen C., ed. Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, with Yale University Press, 2004), cat. n. 285, entry by R. Corrie.

Evans, Helen C., and William D. Wixom. The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843–1261, exh. cat (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), p. 481, no. 317, entry by Rebecca W. Corrie.

Nice article. Love it!