I sat down last Wednesday night with some trepidation to watch the premiere of Bravo’s new reality show Work of Art: The Next Great Artist. For most artists and arts professionals, the show was a harrowing prospect—how can the artistic process and the complex world of contemporary art be reduced to a game show? Artists spend weeks, months, sometimes even years developing ideas for work, so how can we judge their abilities based on what they can do in twelve hours?

For people like me who work at the experimental fringes of contemporary art, there’s even more to fear. Television has never been a friend to the avant-garde, and even such luminaries as Picasso and Jackson Pollock are still regularly subjected to a common dismissal—“my child could do that”—that’s been rankling artists for decades now.

I was especially interested to see Work of Art because one of the contestants, Nao Bustamante, has presented work at the Getty Center before, in our 2006 video art program “Reckless Behavior”. (Download the event flyer and description here.) One of my favorite programs I’ve ever organized here, “Reckless Behavior” presented performance and video work by a number of younger artists, including Harrell Fletcher, Patty Chang, and Kate Gilmore, as well as Ryan Trecartin’s first commissioned work.

Nao Bustamante. Photo: Eleanor Goldsmith

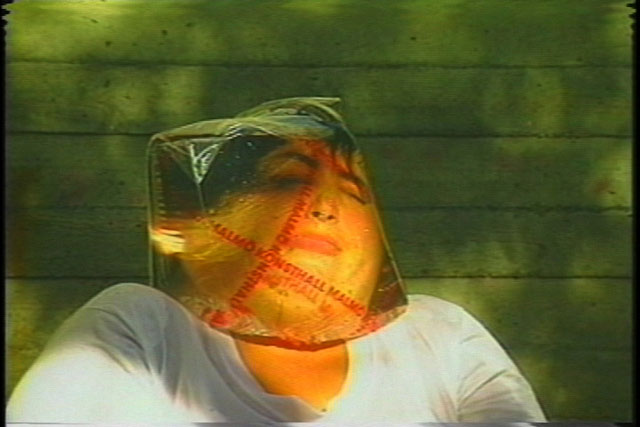

Among the works Nao presented in “Reckless Behavior” was her video Sans Gravity (2000), in which she seals a water-filled plastic bag around her head, taping it closed around her neck. The bag becomes a sort of magnifying lens that enlarges and distorts her face to grotesque proportions. With her face encased in water, Nao holds her breath for as long as possible before ripping the bag open and gasping for air.

Still from Nao Bustamante’s Sans Gravity, 2000

When the work was screened, I noticed that many people in the audience were unconsciously holding their breath, only exhaling at the end when Nao herself was able to breathe again. It is a powerful and visceral work, but not something I’d identify as suitable for a broad television audience.

Reading the first reviews of Work of Art, I was struck by how clearly Nao Bustamante has been cast in the common reality show character of “villain.” Watching the show, it’s easy to see why, since—ever the performer—Nao is clearly reveling in playing that role and making a point to speak her mind as bluntly as possible. But how sincere is she? And how much are the show’s editors trying to amplify her villainous characteristics? And, most importantly, to what degree might the type of art Nao makes—performance and video art dosed equally with conceptualism, identity politics, and camp—be the real “villain” of Work of Art?

For their first elimination challenge, the contestants were divided into pairs and asked to create portraits of their partners. While most of the contestants set about creating figurative paintings or photographs, a small handful of contestants tried conceptual approaches to their portraits. Abstract painter Amanda Williams was eliminated after producing an abstract painting that was deemed not to be a portrait. Nao almost faced the same fate, falling into the dreaded bottom three for her portrait.

Tasked with representing fellow contestant Miles Mendenhall, whose obsessive-compulsive disorder has been a main focus of his onscreen persona, Nao took an obsessive-compulsive approach, documenting his movements as he darted around the studio, and developing a complex formula to transfer those movements to a gridded painting of dots and lines.

With only half a day to complete the work, every contestant’s approach was derivative of something. Nao was looking back to Systems Art and the process-based approach one might find in the 1960s and ’70s in artists such as Sol LeWitt or Hanne Darboven. But whether or not Nao’s approach (and the artistic lineage it referenced) captured any essential qualities of OCD, it was clearly deemed inappropriate for this particular challenge, whose standards were meant to be traditional portraiture as a figurative window to the subject’s soul.

The winning portrait was Miles’s rendition of Nao. Inspired by images from Sans Gravity, Miles “killed” Nao off, so to speak, by photographing her as if drowned and dead, transposing all the raw physical energy of Sans Gravity into an image of stillness and quiet.

What does it mean to have a show like Work of Art turn its attention on the art world? Has contemporary art invaded television, or is television invading contemporary art? It’s clearly a little bit of both, but TV easily has the upper hand.

When I was watching the first episode, my ears perked up when I heard the following sound bite: “I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking: ‘maybe Nao’s a little too established for this show. Maybe Nao’s a little too relatively well-known…’” This is a clip from Nao’s audition tape, and it’s been referenced by several critics (most notably Ginia Bellafante in The New York Times) to point to Nao’s inherent arrogance as a show contestant.

But this wasn’t something Nao ever said as a contestant on the show—the show’s editors pulled it from her audition tape to help enhance her villainous characterization.

Nao has placed footage from her audition video online. It’s hilarious to watch, and it clearly shows that Nao said those words with her tongue firmly in cheek (and wrapped around a sandwich). At the same time, it’s hard for me to know quite what to say about this video. It’s certainly not a standard audition tape, but it’s not quite video art either. Instead, it seems to be Nao’s best guess as to what a hybrid between contemporary art and reality television might look like.

Even if I’m not entirely happy with its implications, Work of Art is great fun to watch and debate. Many staff members at the Getty are watching the show, and we all have our favorite contestants. I imagine the painters have the best chance of winning the competition, but I’m happy to put my support behind Nao Bustamante, and by extension behind video art, performance, and every radical thing those disciplines stand for.

I love your reflections, they really do justice to the question of whether Nao is villain or “villain.” Regarding the genre of her audition tape, I was thinking it was just sketch humor, in the style of recent weirdos on Comedy Central and Adult Swim or even YouTube–a mainstream send-up of her sick and sweet sense of humor.

One of the concerns I have about this show is that it won’t reach a broader audience beyond those of us who already care about art.

Anyone who watches reality tv knows there’s editing, and if it takes an element of shaping the requisite personas to keep viewers hooked, as long as it doesn’t demean them or their work, I’m all for it if it keeps the ratings up, and the show on the air.

Oddly, I find myself wishing a bit more of the (presumably incisive) criticism was making it to the broadcast footage. But overall, I’m pleased as a viewer (and art patron), knowing this is a fine line to walk, and bringing contemporary art to the “mainstream” is no small task.

What a wonderful love letter to one of your own shown artists, Nao. I imagine that you have her in your back pocket and were already in stages to show her work again. Well done Glenn Phillips for taking advantage of the press that Work of Art is getting and using it for self promotion also. Maybe this blog post could have been a better portrait of Nao entitled: Artist As Self Promoter Promoted By Promoter. Or, The Gerbil Wheel.

Villains are cool. Radical wrestling outfit she rocks in that audition tape. Masked Dad approves. It should be the Nao show not the pencil necked geek Miles show.