Imagine you’re a textile conservator at a museum, working with a curator to assess an object that’s been damaged by insects. Or you’re an independent decorative arts conservator interested in how other conservators are cleaning gilded wood. Where do you go to find information to help inform your work? For over 60 years, the answer has been AATA.

AATA, or AATA Online as it’s known today, is a free research database for professionals working in conservation and management of the world’s material cultural heritage—art and cultural objects, architecture, and archaeological sites and materials. With more than 138,000 records, AATA Online covers literature from around the globe from sources as early as the first century BCE. It includes references and abstracts for books, journals, webpages, AV materials, dissertations, and even unpublished manuscripts on topics as varied as radiography, pigments, historic gardens, and the ethics of conservation.

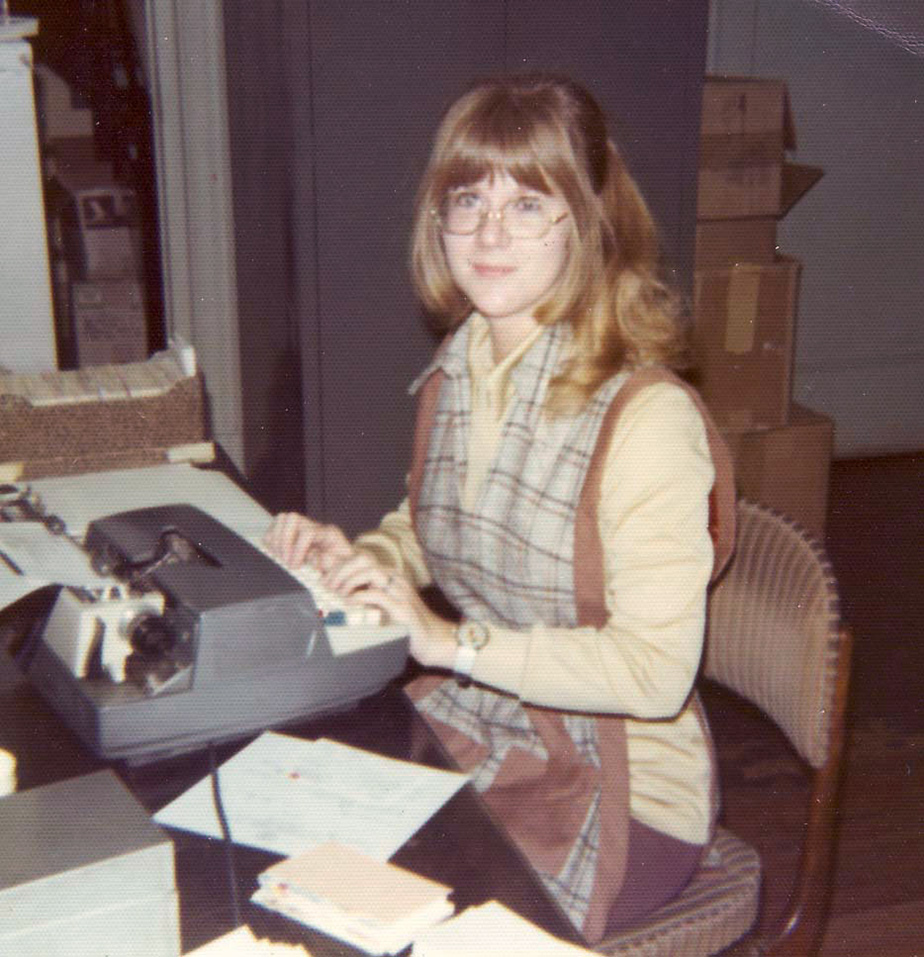

Joyce Hill-Stoner, then-managing editor, typing abstracts to be included in AATA, 1974. Image courtesy Joyce Hill-Stoner

From the Great Depression to the World Wide Web

AATA Online’s origins date to the Great Depression, to 1932 and the Fogg Museum of Art’s publication Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts. Over time, records from Technical Studies merged with those from other sources as AATA changed publishers—from the Freer Gallery of Art to the International Institute for Conservation to New York University to, finally, the Getty Conservation Institute. The name also changed several times along the way, before becoming Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts (AATA) in 1966.

The nuts and bolts of AATA, the way it has been compiled and published, also underwent much change. Before computers, AATA editors underlined index terms in books and journals and copied them onto index cards to be alphabetized by out-of-work actors recruited by managing editor Joyce Hill-Stoner. By the mid-1970s computers began to assist in this work, with the first computer-generated index of AATA produced in 1975 by the British Museum Research Laboratory computer staff headed by Dr. J. Anthony Hall.

J. Anthony Hall (left), principal scientific officer at the British Museum Research Laboratory, and his assistant standing next to the machine responsible for the first computer-generated AATA index. Image courtesy Joyce Hill-Stoner

When the newly established Getty Conservation Institute became AATA’s publisher in 1985, the Institute pursued the goal of providing an electronic publication to the field at large, one that could take advantage of the newly public World Wide Web. In 2002 the long-planned-for goal was achieved—AATA Online was launched on the web as a free research resource available to all.

AATA Field Editors, 2006. Field Editors are exceptionally dedicated; everyone pictured here remains actively involved in AATA Online.

Giving Back to the Field

During its long history, AATA has benefited from the knowledge and expertise of its users, volunteer contributors, and editors. Field Editors, in particular, provide an invaluable service—reviewing abstracts in their areas of specialty before these records go live, helping to ensure AATA Online remains an accurate and trusted resource. Highly knowledgeable in their specialties, they work in museums, universities, and private practice around the world. And they’re truly committed to their work—three long-standing editors, Barbara Appelbaum, Walter Henry, and Judith Hofenk de Graaff, had 60+ years of combined service to AATA Online before stepping down earlier this year.

What makes Field Editors so dedicated? We asked our newest editors, Marieka Kaye and Robin Hanson.

Marieka Kaye demonstrating how to resew a textblock at the University of Michigan. Image courtesy Marieka Kaye

Marieka, a rare book and paper conservator who assesses and treats collection materials for the University of Michigan library system, is responsible for abstracts dealing with paper conservation. Ever since she was a student, Marieka says, “AATA has been the first place I’ve turned to when doing any research…When I was asked to become a Field Editor, I didn’t hesitate to help continue the high quality of this research tool and give back to the conservation community.”

Robin Hanson treating Royal Round Tent Made for Muhammad Shah from the

Cleveland Museum of Art. Image courtesy Robin Hanson

For Robin, who manages the textile conservation lab at the Cleveland Museum of Art and reviews abstracts on textiles for AATA Online, it’s also about giving back to the field. When she was a first-year conservation student, she recalls, “I was recruited by Joyce Hill-Stoner to abstract…like my fellow Field Editor Marieka Kaye, I, too, view my twenty-plus years of involvement as an abstractor and now Field Editor for AATA as a way to give back to the conservation community.”

AATA Online is made primarily by and for the conservation community, but it also serves as a useful resource for anyone doing research into art and heritage conservation, including students, teachers, and writers. A single search quickly leads you into territory that reveals what makes conservation such a fascinating and constantly changing field—from CT-scanning Roman bronzes to preserving indigenous bird-skin parkas. Thanks to dedicated individuals like Marieka and Robin, AATA will continue to grow to support those conserving the world’s cultural heritage.

Interesting, informative article. Thanks!

Hello.just last week I recommended a database building for India also.till today we are taking on it.please guide me how to go about it? Do I need any training?

Thank you for your question about AATA Online! We are always excited to hear about similar projects and exploring ways in which we can work together. We will contact you directly with more information.

Have a query regarding lacquer boxes hoping someone could help me find answers