Most museum galleries have certain things in common. For one, the works are spaced a restful distance apart from one another on the wall. For another, they’re typically organized by school or theme. The focus might be, say, on fashion in the Middle Ages, Cambodian bronze sculpture, or even ancient glass. Visitors are invited to contemplate and compare.

It wasn’t always this way. Back in the early 1700s, when art collecting was a royal affair, princes set up jam-packed galleries in their palaces both for aesthetic enjoyment and to boast about their artistic treasures to the royals down the road.

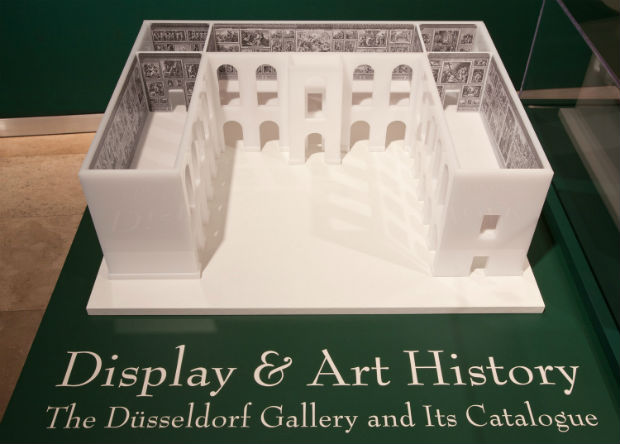

The current Research Institute exhibition Display and Art History: The Düsseldorf Gallery and Catalogue shows how a pioneering gallery presented its art, which later led to practices in modern museums—such as catalogues—that we recognize today.

The story begins in the Baroque period, when European princes displayed their rich collections of paintings and drawings frame-to-frame, floor to ceiling, blanketing enormous gallery walls. This print of a View of a Room at Pommersfelden Palace, with its gargantuan walls of paintings and tiny visitors, shows the overwhelming effect such collections were meant to have on palace guests.

View of a Room at Pommersfelden Palace (detail), Johann Georg Pintz, printmaker; Salomon Kleiner, draftsman; in Representation au naturel des chateaux… (Augsburg, 1728), pl. 18. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B21917

But one German prince had a broader objective than simple braggadocio. Johann Wilhelm II von der Pfalz wanted to make his magnificent gallery more accessible to select visitors.

Between 1709 and 1714, he built next to his palace in Düsseldorf what is believed to be the first free-standing gallery—exclusively to house his treasures, which included around 400 paintings, 46 of which were by Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens.

His collection was formidable, one of the most significant in Europe, in part because of his artistically well-connected wives. (His first wife was the German emperor’s daughter and his second was a Medici, cozy with collectors of Italian masterpieces).

Johann Wilhelm’s nephew and successor, Carl Theodor, took the gallery project to yet another level. He hired painter Lambert Krahe as his gallery director and, by 1763, Krahe had organized the massive collection of paintings by school—Dutch, Flemish, Italian—and invited scholars and viewers, just as today, to draw comparisons. Giles Waterfield, a scholar at the Getty Research Institute and an expert on the history of museums, succinctly describes the Düsseldorf Gallery as “an early attempt to organize works of art as though they were scientific specimens.”

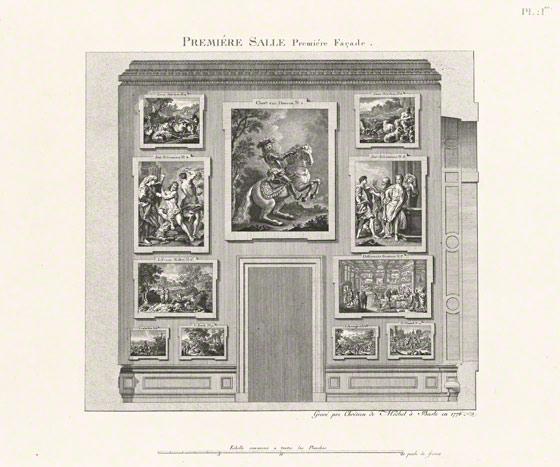

First Room, First Façade of the Düsseldorf Gallery, Nicolas de Pigage and Christian von Mechel, etching in La galerie électorale du Dusseldorff; ou, Catalogue raisonné et figuré de ses tableaux (Basel, 1778), pl. 1. The Getty Research Institute, 70670

Architectural model of the Düsseldorf Gallery in the exhibition, showing the arrangement of paintings by room

In this gallery, artworks had ample breathing room. Though they were still crowded by contemporary standards, the increase in spacing made it easier to contemplate the qualities of a particular work. (Compare the print above to the one below.) One palace guest—these early galleries were not open to the general public—might meditate on a religious work, while another might pause to admire a hunting scene. It no longer took blinders to focus.

“These galleries are dedicated solely to the appreciation of art,” Louis Marchesano, curator of prints and drawings at the Getty Research Institute, told me. “You are invited, by the separateness of this building, to contemplate the works in a way that may have been impossible in a domestic environment.”

In this way, the Düsseldorf Gallery heralded a new perspective and contributed to the birth of the modern museum.

Paintings arranged floor to ceiling, pre-Düsseldorf Gallery style: Fictive Wall of Paintings from the Imperial Collection in Vienna, Frans van Stampart and Anton Joseph von Prenner, etching in Prodromus (Vienna, 1735), pl. 21. The Getty Research Institute, 88-B2961

Really fascinating. I never considered the “restful distance” between paintings in a gallery, or how the way we not just create, but conceive of and display art reflects our values and culture. Thanks for the historical perspective.

How cool! We take our spacious galleries so much for granted these days. Thanks for the historical perspective!

Who knew that a story about the space between paintings could be so interesting!! Loved every moment, and I will be noticing the “restful distance” between paintings from now on. Thanks so much.

I’m almost not sure what the best context for a piece of art would be. “Restful distance” is in itself a distortion, like saying that a piece can only be understood or appreciated if it’s treated almost as separate from the world. I don’t know now what the “best” way to regard a piece of art might be. Some of my faves honestly would take me all day to look at anyhow.

Of course, in many modern museums the flip side of having the “restful distance” between more sparsely hung paintings is having more artwork exiled to storage for lack of exhibition space. Me, I’d rather have salon-hung and at least see everything than be restricted to which artwork curators deem deserves my “meditation”.