George Hein, a leading authority on museum education whom the Museum’s Education Department invited as a guest scholar this spring, says that museums are inherently educational. The professor emeritus in the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences at Lesley University sat down with me to share his thoughts on museums—and offer some guidance for both museum leaders and visitors on how to make a visit to one a rich and memorable experience.

Why is education important to museums?

Museums were founded as educational institutions. One way or another, museums inevitably interpret their collections for visitors. To assume they aren’t educational institutions is to shirk their basic responsibility. A museum is only a warehouse, an archive or a storage place for objects if it doesn’t welcome visitors and, in some form, attempt to educate them.

What distinguishes museum education from education, or from museum studies?

Some people have written that the way people learn in museums is different from the way people learn in schools, in families or other categorical distinctions. I don’t believe that. Education is education and learning is learning. People learn in an active way by engaging in experiences and reflecting on what they have done, whether it’s reading, looking, or using their hands. Learning is a matter of engaging the mind.

You’ve written about museums as progressive institutions. What do you mean by that?

For me, the question is not just, “does the museum engage in educational practice?,” but rather, “does it engage in progressive educational activities that are connected to improving society?” John Dewey’s [education reform] ideas were used by a number of museum educators in the early 20th century. For example, Anna Billings Gallup, the curator of the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, was cognizant of the fact that one-third of children in Brooklyn didn’t go to school. So she tried to create activities that would allow children to get an educational experience. She recognized that the museum could provide a social service.

What are some specific ways museums can encourage learning?

Museums have different strategies and, to some extent, they have a strange and schizophrenic attitude toward their visitors. The goal of art museums is generally for people to look long and hard at works of art. But museums also tempt visitors to keep going on to the next object since they have so many objects displayed. The way people visit museums creates tension between really focusing on learning how to see, and pursuing all sorts of other goals. Museums are also social places. People tend to visit in groups or families. So that contemplation and reflection on art is undercut by the other ways that museums serve the public in our culture.

The Getty is a wonderful example of an institution that has an increasingly interesting and rich collection and at the same time competes with itself by providing an enormously rich aesthetic experience besides the art. It’s a wonderful place to be. But there’s a built-in tension.

What are some ways museumgoers, such as parents or students, can make their visit more meaningful or educational?

The more you know, the more you learn. For school groups, the more that museums can provide information beforehand and follow up afterwards, the richer the experience can be for children.

Some museums have guides, and many have a variety of interactive ways to provide a richer experience for visitors. An educational gallery at the Getty Villa talks about how a bronze statue is preserved. In another exhibit, La Roldana’s Saint Ginés, you’ve turned the gallery into an educational experience. It explains the physical means by which the objects were made, the people who made them, and the culture in which that type of work was done.

What can you say about the learning habits of museum visitors?

For me, it’s most important to remember that no exhibit will be interesting or useful to everybody no matter how much you try to divide people into groups. There’s a wonderful French study that came out 30 years ago that describes some visitors as fish sliding through the museum, while others are like grasshoppers who hop from one exhibit to another, and some are like ants that follow a careful trail, while others are butterflies that flit around. Others have described visitors as serious students, browsers or social visitors. None of those categories are as useful as understanding that individuals have their own ways of engaging with the world. As many of my colleagues point out, your background, who you are with, and the physical environment all contribute to making a museum visit meaningful for you.

What was your first experience of museums?

My first conscious experience of museums was as a child when, because we were planning to immigrate to the U.S., I got to go to Rome and Naples. I remember seeing the Sistine Chapel and I vividly remember going to Pompeii. They were wonderful experiences in a very tense time for my parents. It was before the Second World War.

Later, I grew up in Binghamton, NY, a town without much in the way of museums, but there was a wonderful museum upstairs in some municipal building. This upstairs room had a lot of the history of the area. They had arrowheads and all kinds of historical material. A friend of mine and I used to go down there and hang out. There was nobody there. It was a wonderful place just to go.

You’ve been a guest scholar at the Getty for three months now. How would you describe the experience?

The Getty is a great place to work. You are surrounded by colleagues and by a lot of people who are interested in your work and who are doing work that’s interesting to you. The facilities and care they provide the scholars is marvelous. The research assistant and staff help you in any way they can—and you are in a gorgeous aesthetic setting.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Thank you for publishing this, it’s wonderful to hear from G. Hein in this context. Can you say anymore about other results of Hein’s residency that might be shared with the community?

Hi Kris — Thanks for your question. Dr. Hein’s stay at the Getty was primarily devoted to research for a forthcoming book. His proposal, with details on the book project, is as follows:

My current research is devoted to developing a manuscript entitled (tentatively) “Democracy and Museums: The Social Responsibility of Museums.” In recent years, there has been an increased demand that museums serve a public function broader than preservation, collection, and display. In 2002, the American Association of Museums called for “civic engagement” by museums. Journals with titles such as “Museum & Society” (launched in 2003) and Museums & Social Issues (published since 2006) — the latter addresses “social issues and the engagement of museums in these issues” — are now in circulation. Professional meetings increasingly address the responsibility of museums toward social concerns.

This new wave of interest in social responsibility for museums is only the latest resurgence of a longstanding theme in the history of museums. Almost 70 years ago, Theodore Low published a monograph entitled “The Museum as Social Instrumental,” addressed primarily to art museums. This short book is one of a number of writings dating back to the origins of museums, encouraging them to be socially active through their educational function.

John Cotton Dana has long been recognized as an advocate of a social role for museums; and a century earlier this view was integral to the founding of Charles Willson Peale’s American museum.

On the level of practice, the engagement of museums in social change is debated in the profession. On a more theoretical level, various justifications have been advanced for linking museums and social action ranging from economic considerations – if museums are “relevant” to local issues, or if they address topics that relate to local (or global) civic concerns, they will be able to attract visitors and overcome economic difficulties – to more moralistic rationales that museums have an obligation to contribute to major social concerns, such as sustainable practices (going “green”) or supporting various social agendas.

Yet, neither the practical consequences of such actions for museums, nor their theoretical basis has been thoroughly examined. I argue that:

a) Education is the primary purpose for museums (as outlined in my chapter on Museum Education in S. Macdonald, editor,” Blackwell Companion to Museum Studies,” 2006).

b) Progressive education is the appropriate educational theory for museums. (I have discussed this subject in my various articles on constructivist educational theory.)

c) Social concerns are integral to progressive education, as carefully elucidated in John Dewey’s writings.

Hello George,

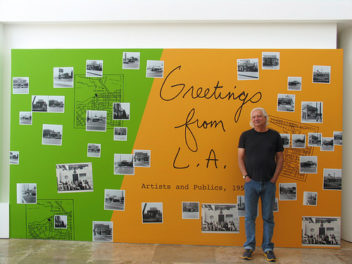

This is a wonderful collection of views encompassing the most important aspects of learning and museums. Best wishes for your book. The photo is a gem!!

Best wishes

Janette

Muchas gracias por compartir sus conocimientos! Soy de Paraná, Entre Ríos, Argentina y el año pasado visité el Paul Getty, de allí me traje unas tarjetas de explorando el arte que son una especie de tarjetas para explorar diferentes detalles de las obras, la traje y como soy Directora de un Museo de Ciencias Naturales en mi Provincia he podido adaptar este recurso que creo es muy importante porque permite que los niños puedan explorar el Museo junto a sus familias. Muchas gracias! y felicito por ese hermoso Museo!!! Prof. Gisela Bahler