Julio César Pérez Hernández, architect and author of Inside Cuba, visits the Getty Center this Thursday to talk about Cuban architecture in conjunction with the exhibition A Revolutionary Project: Cuba from Walker Evans to Now.

Evans’s photographs of Cuba from 1933, which form the heart of the exhibition, offer a remarkable portrait not only of the people of the island, but also of its architecture. Julio shared his observations on several buildings and details that drew Evans’s eye, and what stories they might tell.

Havana Cinema

Here is classic Cuban colonial architecture—as revealed by the tall, narrow doorway and the building’s openness to the sidewalk, welcoming street life and human exchange. Hand-painted signage is attached to the walls: in 1933, neon signs were yet to come. Posters advertise American films (White Eagle and A Farewell to Arms), showing the dominant influence of the U.S. in Cuba. The presence of black men and women on the streets is also a frequent feature of Evans’s photographs.

Havana Cinema, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.142. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cuban Children

An elaborate wrought-iron grille stands between the photographer and a child who looks out with a lost gaze, as if trapped behind the bars of a prison. Evans once again emphasizes a tall, narrow doorway in his composition. French louvers or parisiennes are visible behind the grille, a classic feature of traditional Cuban architecture.

Cuban Children, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.144. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Building Facade

This photograph shows the rhythm of light and shadow created by the arcades of traditional Cuban architecture. Such two-story buildings with high ground floors and mezzanines were prevalent in Cuba for centuries. The elaborate grilles on the balconies, with their refined metalwork, are also frequent features of colonial buildings. The symmetry and order in Evans’s photograph allude to the static character of Havana street life.

Building Façade, Havana, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.236. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

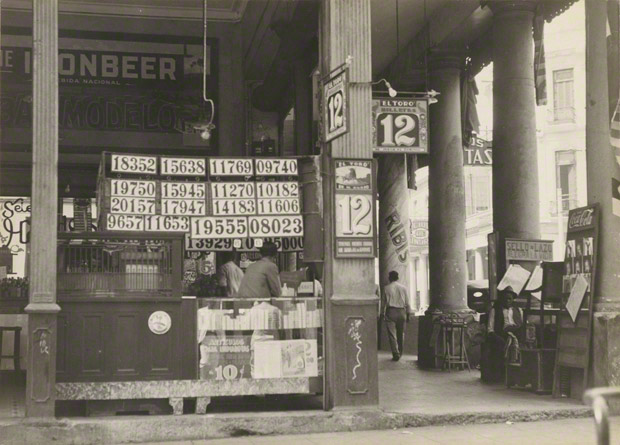

Colonnade Shop

Havana was called “the city of columns” by Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier. Columns—and later porches—were the most distinctive feature of buildings around the main squares in the old city. The arcaded and porticoed streets would come to be called calzadas. This photograph shows the harmonious coexistence of cast-iron columns from the U.S. and stone columns with Tuscan capitals characteristic of traditional Cuban architecture. (Also note the lottery bills: gambling was allowed in 1933.)

Colonnade Shop, Havana, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.266. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

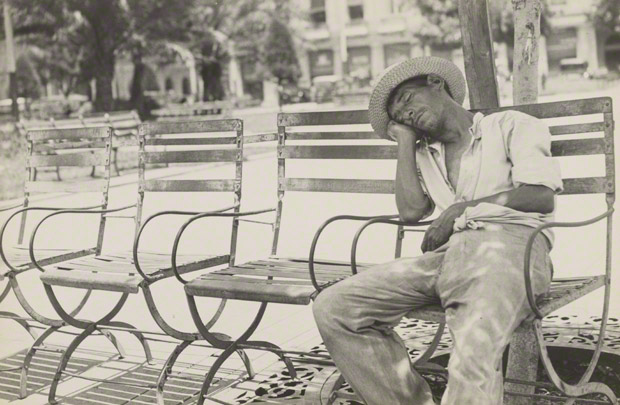

Parque Central II

The Central Park was the heart of Havana in 1933, when Evans came to Cuba. It’s an open space that is part of the famous Paseo del Prado, with recreational facilities such as theaters, shops, cinemas, and hotels. Open-air cafes were built there in the second half of the 19th century. The sleeping man alludes to unemployment and poverty, in contrast with the elegance of the park.

Parque Central II, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.166. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cuban Bohío

Here Evans captured the housing of the poorest sector of Cuban society. The primitive hut with a thatched roof—still in use in rural areas—is built out of palm leaves, with walls of palm wood.

Cuban Bohío, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.173. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Plaza del Vapor, Market Area

A very popular marketplace at the end of the famous commercial street Calzada de Galiano, which was lined with international shops such as Woolworth’s, the Plaza del Vapor was demolished in 1960. Before the Revolution of 1959, this urban space, located in the Colón (Columbus) neighborhood of Centro Habana adjacent to Old Havana, had become known as a center of prostitution, where women were exchanged as merchandise.

Plaza del Vapor, Market Area, Havana, Walker Evans, 1933. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.956.278. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wonderful photos, wonderful people, wonderful country…too bad I can’t afford to emigrate there with my family. My son Curtis plays baseball and piano and drums and fences and my daughter Siena does Ballet as a 7 yr old as well as skateboards with me her father . Anthea my lady and I shared a short vacation in Havana and Pinar del Rio about a decade ago and have been reccomending Cuba to everyone ever since. Our Salsa dancing needs some improvement before we return . Thanks for the historical shots which my son especially enjoyed …Viva Cuba Libre !