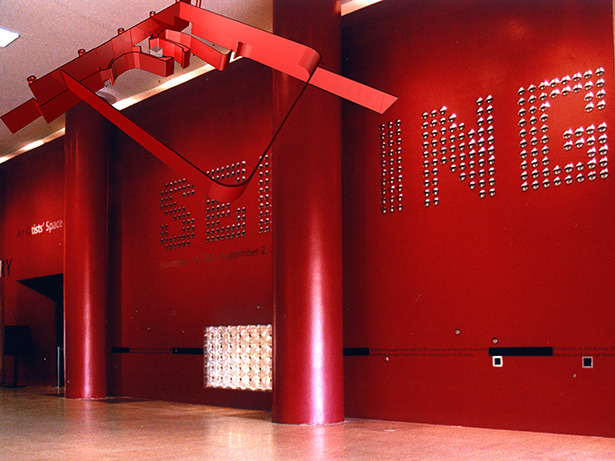

Machine Project’s humorous “Giant Hand” installation at the Hammer Museum tackles wayfinding through humor. Photo courtesy of the Machine Project

More and more museums are inviting artists to go beyond hanging their art on their walls to create engaging visitor experiences inside the museum. At a panel discussion earlier this week, we invited curators, educators, and artists to talk about three pioneering artist-museum collaborations in L.A.

Robert Sain, former director of LACMA Lab, and Christoph Korner, partner at GRAFT architects, discussed their work on the Lab’s Seeing exhibition; Asuka Hisa, director of education and public programs at the Santa Monica Museum of Art (SMMoA), and artist Olga Koumoundouros presented their collaborative Wall Works installation (detailed in a great interview on KCET’s Artbound); and Machine Project’s Mark Allen and Elizabeth Cline (formerly of the Hammer Museum) discussed Machine’s yearlong public engagement residency at the Hammer.

Though the projects spanned three very different institutions and well over a decade, several common themes emerged. For more from the event, see the live tweets on Storify.

Museums Need to Embrace Artists

Working with artists to create socially engaged projects inside the museum is fundamentally different from, and more challenging than, simply commissioning works of art. It means “inviting artists into the life of the organization,” said Sain, plunging the museum into the thrill, mess, and risk-taking of the creative process. For art museums, which uphold the value of learning and creativity, this risk is required to “do internally what they profess externally.”

Friction and Pushback Are Normal

Differing perspectives create tension, sometimes unpredictably so. “We were surprised how much friction there was [on some projects], whereas others sailed through,” said Cline of Machine Project’s residency at the Hammer. Giant guest book in the lobby? Sure. Tiny guest book? No way. Some staff worried it would suggest that visitors’ thoughts weren’t important.

To some inside the museum, artists’ proposals can seem frivolous, disrespectful, or just plain amateurish. When artist Daniel Joseph Martinez placed objects from LACMA’s collection into holes in the floor, a conservator huffed to Sain, “no real curator would ever do such a thing.” (His response: “Precisely the point.”)

Allen said this pushback is exactly what energizes him: “For artists, the most interesting thing about working in museums is about how difficult it is.”

Confusion Can Bring the Museum Alive

Museums like to tell and explain, but artists like to dialogue, provoke, and confuse. Confusion is a profound tool, said Koumoundouos, because it prompts us to ask questions, which “means we’re alive.”

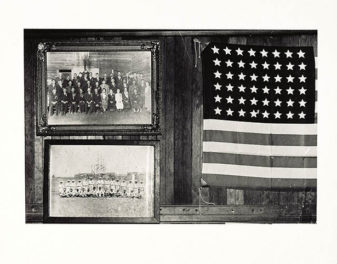

“Confusion can make us slow down and really look,” Korner added. For LACMA Lab’s landmark Seeing exhibition, he threw visitors off balance from the get-go by embedding intimate peepholes into an oppressively authoritarian title wall. What should visitors do: approach or run?

Visitors are drawn to peepholes that show tiny replicas of Michelangelo’s Moses in a variety of contexts, from embedded flowers (“Moses in the roses”) to a U.S. flag-draped shopping experience. Photos courtesy of Christoph Korner / GRAFT Architects

Confusion and humor are hallmarks of the work of Machine Project, whose interventions at the Hammer included encouraging visitors to wear bells and inviting houseplants for a spa day. Many of their events and installations took place in the lobby, courtyard, or corridors for this very reason. “We tried to confuse the spaces,” Allen said. “We preferred strange, interstitial spaces, not galleries.”

Because artists act as curators, architects, designers, educators, and event programmers all at once, their work also confuses divisions inside the museum, inviting—in some cases forcing—increased collaboration among staff.

Documentation Is Key

Artists’ projects in museums are typically ephemeral, which makes documenting them essential. They’re also full of lessons that can guide future projects inside and outside the walls, as the Hammer and Machine Project reflected in their collaborative report released earlier this year. (“Highly recommended for anyone who wants to see how the public engagement sausage gets made,” says Machine.)

The Wall Works project at SMMoA incorporates documentation throughout each project, beginning with an art kit sent to participating schools that includes supplies and a short video introducing the artist’s process. Extensive documentation means that any past Wall Works project “can be remade and reinterpreted” at another museum, said Hisa. For an institution without art holdings, this rich documentation serves as a rich archive of ideas that “we can consider our ‘collection’.”

Olga Koumoundouros’s Wall Works installation, CART, includes drawings made by local schoolchildren affixed to wagon wheels created with magnetic paint. Photo courtesy of the Santa Monica Museum of Art

Artists Disrupt the Institutional Voice (for the Better)

Perhaps the most dramatic effect of artists’ interventions in museums is to disrupt the institution’s voice, and in doing so to transform the museum from a place of information and authority to one of experience and curiosity.

At the Hammer, Machine Project explicitly set out to intervene between the museum and visitors and prompt them to ask, “who’s talking to me?” Through interventions such as an overnight “dream-in” inspired by Carl Jung’s Red Book, Machine Project “transformed institutional space into visitor space and gave visitors permission to utilize the museum.”

Through Wall Works SMMoA creates spaces of dialogue between artists, museum staff, and local students, from which all benefit. Speaking of her work with kids, Koumoundouros said, “I want to see what they think, have them throw that [idea] back, and see what we can build together.” This dialogue enriched her process as an artist. “I realized it wasn’t about me. There was learning on both ends.”

Inviting artists into the institution, the panel discussion revealed, has ramifications far beyond any individual project. Including artists means taking risks and ceding control; it means changing how museum staff work together; and it even means shifting what a museum is, from a space for art to a space of art.

Panelists with bug: Moderator Peter Tokofsky of the Getty Museum’s Education Department with Christoph Korner, Elizabeth Cline, Asuka Hisa, Olga Koumoundouros, Robert Sain, and Mark Allen in front of John Baldessari’s Specimen (after Dürer), commissioned by the Getty in 2000. Artwork © John Baldessari

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks