Frances Terpak and Peter Louis Bonfitto, co-curators of the Getty Research Institute’s first online exhibition The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra, took your questions on Instagram last week. Both are passionate about the value of scholarship and the need to protect heritage sites around the world. Here, for the record, your questions and their answers.

Were any artifacts salvaged before the war started, or records of what existed? And what became of any local archaeologists, historians, museums dedicated to the Syrian patrimony? Thank you! —@burntsmurff

Details are unclear, but there are some reports that objects were moved to Damascus, although we also can assume some looting of objects occurred along with the known destruction of monuments during the occupation. The Syrian Ministry of Culture and international teams of archaeologists kept records of the site. Sadly, we know that many local archaeologists and other specialists have been killed during conflict or have been forced to flee. —Peter & Frances

What dates was Palmyra at its zenith? —@nicquik

The mid-second to the third century CE. This is when Palmyra was a major trading hub in the region. —Peter & Frances

Temple of Bel, 1864, Louis Vignes. Albumen print, 8.8 x 11.4 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.R.15

What is the most fascinating thing that has been learned or discovered from the Getty collection of photographs of #AncientPalmyra? —@mrjuliantyler

One of the important features captured in the Vignes photographs of the Temple of Bel is the presence of mud-brick houses, which documented the contemporary settlement Tadmor (removed in the 1920s by archaeologists). Comparing that view to Cassas’s plan of the Temple of Bel shows that he also documented the same structures. These domestic structures show the long history of Palmyra and that the site was continuously lived in for thousands of years. —Peter & Frances

Is anyone working on a 3D remodeling of what #AncientPalmyra looked like? —@mrjuliantyler

Yes! There are a number including NewPalmyra.org. —Peter & Frances

Before the war, what methodology was used to preserve records? What has been the major challenge since then in trying to keep and maintain what is now left? —@sansregarde

Archaeological excavation records have been published for nearly a century documenting the buildings, artifacts, and other urban features. The challenges now are many, including intentional destruction, collateral damage during the conflict, and looting. —Peter & Frances

Yesterday a recreation of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph has been installed in Piazza della Signoria in Florence for the G7. It is amazing! As amazing would be there just to see the online exhibition. Well done! ✨ —@babydoll6277

If you’re interested in more examples of digital reconstructions, see NewPalmyra.org —Peter & Frances

Did all of the famous structures at the site survive from antiquity, or were some restored/reconstructed in the 19th or 20th centuries, as happened at many sites dating from antiquity (like at Volubilis, for instance)? —@ghastlyfop

Nineteenth-century curiosity about Palmyra’s monuments, sculpture, and inscriptions transformed into professionalized archaeology by the turn of the 20th century. See the Modern section of the online exhibition for more discussion of what archaeologists did in the 20th century. One example is the Tetrapylon. —Peter & Frances

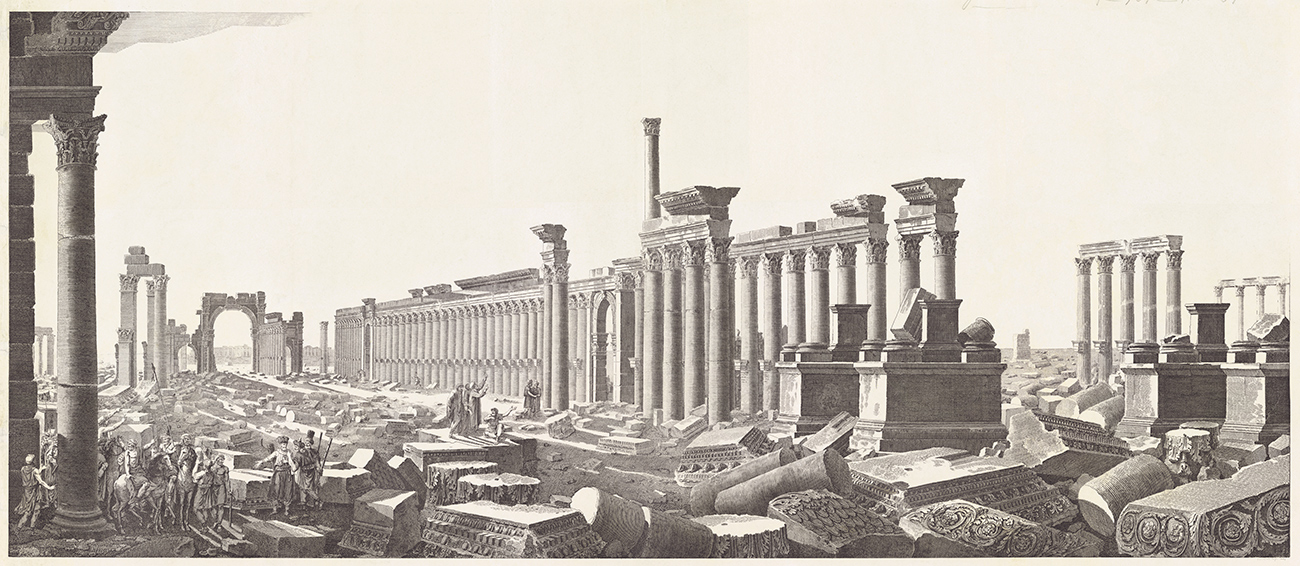

Colonnade Street featuring bases of Tetrapylon in foreground, ca. 1799, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas. Proof-plate etching. 35.8 x 16.9 in. The Getty Research Institute, 840011

Who is Zenobia? What and how much do we know about her? —@revolwution

Zenobia was the ruler of Palmyra starting in 267 CE. She lead a five-year military campaign that increased Palmyra’s territory until she was defeated in 272 CE by the Romans, and Palmyra became part of the Roman Empire. Differing accounts of her capture and fate appear in classical and post-classical sources—the most famous being that she was lead back to Rome in golden chains. —Peter & Frances

1. When was the first tomb tower built at Palmyra and for whom? 2. What unexcavated sections of the city remain (if there are any)? —@art_around_nyc

The first major tower tombs date to the 1st century CE. These tombs were essentially mausoleums for elite families in Palmyra and mark the economic rise of the city as a trading center. The site is vast, and generations of archaeological work could still be undertaken once the conflict has ended. —Peter & Frances

Valley of the Tombs, Charles François Le Tellier after Louis-François Cassas. From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 101., Etching, 12.9 x 18.3 in. The Getty Research Institute, 840011

Has Palmyra been well documented in the past in terms of photographic evidence, written evidence, and collections of objects which could be transformed into a wonderful digital library for the people of Syria who have been flung far and wide by this terrible war? Thinking of the value of the partnership between the British Library and Qatar Digital Library for schools, scholars, researchers and the world wide audience. —@linakerstreet

Yes! Our online exhibition heavily features the first photographs ever taken of the site taken by Louis Vignes taken in 1864. Check out the Additional Resources page to see other projects by individuals and institutions. —Peter & Frances

While serving as a modern-day Monuments Man in the Middle East, Lt. Col. Andrew Scott DeJesse gathered statistics to show the positive impact of cultural preservation on countries that are trying to reestablish themselves after major conflicts. Is there someone compiling and publishing research supporting cultural preservation? —@Rekceb2

On February 8, the Getty Research Institute held an event where we invited a number of specialists working on the topic of Syrian cultural heritage. Videos of the entire event are available on YouTube and also can be found on getty.edu/palmyra under the Additional Resources section of the site, under Multimedia. One thing that might be of particular interest to you is most of the new visual information we are receiving is only from satellites because we don’t have images taken on the ground. —Peter & Frances

Temple of Bel, southwest exterior corner of the courtyard, 1864, Louis Vignes. Albumen print. 8.8 x 11.4 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.R.15

I’ve been to Palmyra for New Year’s Eve in 2010. When I saw the photos acquired by the Getty in “Breakfast in the ruins” I thought some of what I saw in these early photos were missing by 2010, esp. around the courtyard. What were the changes between then and 2010? I’m also wondering how much of what I saw from the watchtowers, tower tombs, and the colonnaded street are still there? Is Temple of Bel entirely gone? —@Elif_ozgen

The photographs in the exhibition were all taken before any archaeological excavation had been conducted on site. Decades of work changed many of the major features of the site. If you haven’t seen the Modern section of getty.edu/palmyra, you can get more information there. Unfortunately, most of the major monuments of the city have been destroyed. Only the Temple of Bel’s gateway to the inner temple remains. —Peter & Frances

Temple of Bel, 1799, Lepagelet and Pierre Gabriel Berthault after Louis-François Cassas. Etching, 11.8 x 18.5 in. The Getty Research Institute, 840011

___

Thank you for all your questions. Follow @GettyMuseum on Instagram for more Q&As with our experts, as well as behind-the-scenes glimpses, campus photography, stories about art, and lots of pretty things.

Hi so i am actually young and i need to know a couple of questions I ‘ve been looking all around the internet but could not find one answer.

1. How long has Palmyra been there?

2. How long did it take to build Palmyra?

3. What materials were used to make Palmyra?

4. What were its functions (what was it used for?)

Thank you if you can help me!!!!!!