The Dream of Pope Sergius, late 1430s, workshop of Rogier van der Weyden. Oil on panel, 35 1/2 × 32 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum (left); The Meeting of the Three Kings, with David and Isaiah, before 1480, Master of the St. Bartholomew Altarpiece. Oil and gold leaf on panel, 24 3/4 × 28 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum (right)

The French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA) is launching an ambitious project for scholars and the broader public that proposes an innovative way of accessing medieval Christian images. By building complex and nuanced vocabularies of keywords and terms, the “Ontology of Medieval Christianity in Images” (OMCI) will allow databases to better represent how such images depict philosophical and spiritual themes that have been diminished or even ignored in current approaches.

Traditionally, Western art history has favored examining narrative aspects of medieval Christian images over conceptual ones. As art historians have adopted digital media in their work, this preference has been reflected in the structure of databases, which have tended to organize information about medieval Christian artworks around themes related to biblical and Christian places, events, characters, and objects.

However, medieval Christian artworks depict much more than narratives. In the Christian tradition, the material and spiritual worlds, and the course of history itself, are expressions of God’s law for the universe. The very structure of medieval Christian images—as expressed in their content and composition—often mirrors that overarching cosmological order.

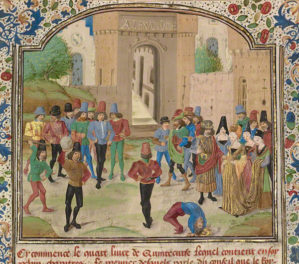

In other words, the relationship between pictorial content and religious ideology in medieval Christian images is much more nuanced, and more expressive, than simple storytelling. The OMCI is concerned with this ontological level of analysis: the OMCI team of art historians, graduate students, and technology experts intends to build a web resource that will identify keywords and iconographical themes linked to medieval Christian knowledge and belief systems. These will be augmented by examples from the art of that period—such as the images featured above—that reflect both cultural values and Christian ideals.

Consider, for example, the episode of the (in)famous expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise—or the entrance of humans into the earthly realm—in the book of Genesis. In the medieval Christian bronze artwork the Bernward Doors (made in 1015), Panel 1 depicts the magnificent Tree of Life. In Panel 4, while Adam and Eve exit Paradise to the right, humans’ inevitable death is rendered conceptually as two trees flanking the armed angel to the left. These two trees once formed the Tree of Life depicted in Panel 1.

Detail of panel 1 of the Bernward Doors, 1015. Bronze. © Archiv Monheim – Dom Museum Hildesheim

Detail of panel 4 of the Bernward Doors, 1015. Bronze. © Archiv Monheim – Dom Museum Hildesheim

When it was whole, the Tree of Life perfectly unified the material and spiritual principles of life, and therefore eternity. But when Adam and Eve leave the Garden of Eden for the earthly world, this primordial expression of life cleaves in two. As seen in Panel 4, once split the Tree of Life takes the shape of two smaller trees, one depicted above (at top left) and the other below (at center): the tree at top represents a tortured soul dying from its separation from God (Augustine of Hippo, De Genesi), while the tree below, weak and wilting, represents the human body—bound to die and return to dust upon separation from the soul.

Unfortunately, Western bias toward the narrative content of images means that thematic concepts such as these—materiality, time, the death of the soul, the death of the body, organic unity, division, and mutation—do not appear as keywords in iconographical indexes, despite how fundamental they are in Christian and non-Christian theologies, cosmologies, and philosophies. Thus, by correlating ontological themes with searchable keywords, the OMCI aims to correct the imbalance toward narrative analysis in medieval Christian art history.

During the early stages of the OMCI’s development, and especially because of its pioneering nature, the INHA team and I sought advice from colleagues at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), who have proven expertise in building research databases and controlled vocabularies—a decision that behooved us if we desired our project to set standards in the field. The Research Institute has decades of experience in producing electronic tools for art historians, evidenced by their production of the Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), among other online resources. Furthermore, the GRI and INHA have had a close relationship for many years and recently signed a framework agreement stipulating that our two institutions will share resources and expertise.

For these reasons, I visited the Research Institute in late 2015 and worked closely with two internationally known experts, Patricia Harpring and Murtha Baca, focusing on the process of creating a vocabulary of terminology for the OMCI project. Happily, we collectively decided that the Getty’s vocabulary experts will help the OMCI team build a bilingual vocabulary of iconographic terms, and the INHA will, in turn, contribute new data to the Research Institute to enrich their world-famous vocabulary tools. As the OMCI team moves forward, I am increasingly motivated by this auspicious collaboration—a partnership that bodes well for the future of symbolic analysis and digital resources in the study of medieval Christian images, and for the field of (digital) art history at large.

Thanks interesting work, I have not seen for many years since graduate studies. atk