“Gérôme forged narrative practices that would take the cinema decades to invent,” art historian Marc Gotlieb told a packed auditorium recently in a discussion of The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, which closes this Sunday.

Really? How could a 19th-century academic painter like Gérôme—a man adamantly opposed to modernism—have contributed to cinema, the quintessential modern art form?

For one thing, Gérôme’s images pervaded popular culture of the early 20th century, both in Europe and the United States. “Entertainers like Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey’s restaged Gérôme’s pictures in living form,” Gotlieb said. “And directors of early Hollywood spectacles borrowed elements from Gérôme, both sets and plot elements.”

But Gérôme’s contribution to cinema was more than costumes and sets. His ingenuity lay in his innovative use of space and time—what Gotlieb calls his “cinematic imagination.”

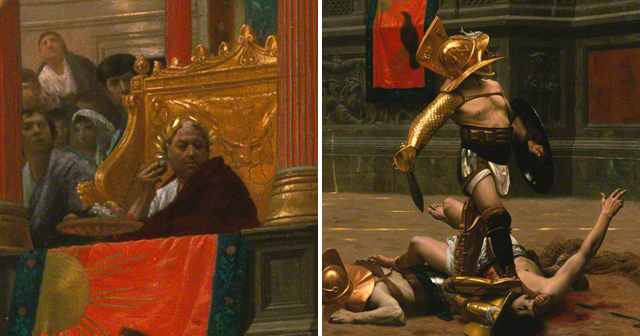

Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1872. Phoenix Art Museum. Museum purchase. Photograph by Craig Smith

The tracks of the chariot races are still fresh on the ground, and we can imagine the thundering horses and the speeding chariots as they raced by. The gladiator looks toward the vestal virgins in the stands as they all feverishly point their thumbs down, pollice verso, indicating the death of the loser. But the final decision is left to the emperor, who sits in his viewing box, slowly eating from his bowl of figs.

What’s special here? “Gérôme spins time on several different axes”, said Gotlieb, who compared the effect to a popular technique in film known as bullet time. Temporally, the scene is slowed so dramatically that we can see events that would normally be undetectable. But spatially, we can still move around the scene as normal, gaining the ability to move around the undetectable event and see it from different perspectives.

This effect was popularized in action films like The Matrix, where the main character, Neo, is shown dodging a bullet in slow motion as the camera moves around the scene at normal speed.

In Gérôme’s Pollice Verso, the effect is similar. As the gladiator looks to the stands, we feel the fervent shouting and pointing of the vestal virgins. The emperor, however, moves in a different sphere of time, slowly eating away at his figs, unfazed by the chaos before him. We, the viewers, are free to move around the scene at our own pace. We look from the vestal virgins, to the gladiator, to the emperor, each flowing at a different speed.

This technique prefigures the ability of cinema to depict several moments in one shot, to fast-forward, to slow down, to stop.

Is it any surprise that Pollice Verso was an inspiration for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator? The story goes that upon seeing the painting, Scott decided to sign on to direct the project.

Gérôme was criticized in his day for confusing literature with painting. Before the invention of film, passage of time could only be represented in literature, poetry, and spoken word. Gérôme broke that mold—but his method wasn’t fully understood until moving pictures could capture the experience for us.

Nice article – lots of interesting points here. But I have to wonder about your statement toward the end, about Gerome being the one to break the mold (with depicting the passage of time visually). If you look at Botticelli’s “Scenes of the Life of Moses”, which pre-dates Gerome’s work by several hundred years, the passage of time is depicted here quite beautifully also, although in an entirely different way! I’m not sure if Botticelli was the first to employ this cinematic technique (doubtful), but his piece is definitely a masterpiece in its own right: http://www.1st-art-gallery.com/thumbnail/115102/1/Scenes-From-The-Life-Of-Moses.jpg

That’s awesome, this painting was clearly ahead of its time! I thought it was a screenshot from Gladiator that was manipulated, only to realize it was painted over a century ago.

I’m looking for the name of one of Gérôme’s photography pieces. It was displayed at the Getty last year – a nude woman suspended in the air encircled by baguettes. If anyone knows the title of this work your help would be greatly appreciated. I want a print so badly!

-Kimberly

Kimberly, I believe that the picture you saw wasn’t by Gerome. There was a concurrent photographic exhibit at the Getty, called “Tasteful Pictures” by various artists.