From the new letters: René Magritte painting Les promenades d’Euclide, 1955 (Oil on canvas, 64 1/8 x 51 1/8 in.). Getty Research Institute, René Magritte Letters to Alexander Iolas, 1954–1962. © 2013 C. Herscovici, London / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. With the exception of uses made in accordance with the U.S. Copyright Statute, including, without limitation, fair use, reproduction including downloading of René Magritte works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The Getty Research Institute recently acquired a small group of letters from René Magritte to Alexander Iolas, adding to an already impressive archive of Magritte material in its special collections. These letters provide an intriguing glimpse into the relationship between the Belgian Surrealist and the dealer who would play an important role in promoting him. They also demonstrate Iolas’s close involvement with the sales of Magritte’s paintings, as well as the planning of his exhibitions.

The association between Iolas and Magritte began in 1947, when the artist had a one-person show at the New York-based Hugo Gallery. The Hugo had been founded when Iolas (who was born as Constantin Koutsoudis in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1907, and died in New York in 1987) ended his career as a ballet dancer on account of injuries. Iolas worked with Magritte first in his capacity as the Hugo Gallery’s director, and later when he replaced the Hugo with a gallery established in his own name.

The Iolas Gallery represented Magritte until the painter’s death in 1967, not just in New York, but also in subsequent spaces opened in Paris, Geneva, Milan, and Madrid. Through his close connections to collectors, Iolas was responsible for significantly raising Magritte’s profile by placing his work in important American collections in the postwar years, such as that of the Menils, who would become among the artist’s most important patrons.

Letter from René Magritte to Alexander Iolas, October 3, 1955. Getty Research Institute, René Magritte Letters to Alexander Iolas, 1954–1962. © 2013 C. Herscovici, London / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. With the exception of uses made in accordance with the U.S. Copyright Statute, including, without limitation, fair use, reproduction including downloading of René Magritte works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

At the moment of the earliest letter in the group, which dates to 1954, Iolas had just begun to spin off his own gallery from the Hugo, and Magritte was still in the midst of establishing the terms of their working relationship. For instance, in a letter dated May 25, 1954, Magritte writes, “But one must make a living. And I count on you to work miracles, which will give me the peace of mind that is indispensable to getting my work done.” In the same letter, Magritte gets down to business, negotiating with his dealer over the price he would need to pay for two large canvases from that year, L’empire des lumières (The Empire of Light, now in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice) and Le Monde Invisible (The Invisible World, in the Menil Collection).

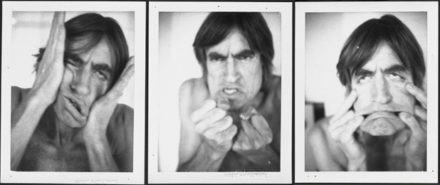

In a letter dated September 10, he responded to Iolas’s desire to have greater say in his career by instructing him to act on his behalf for the Carnegie International: “get in touch directly with this institution, so that you yourself can send a painting, chosen by you, to be shown at [the] competition exhibition.” Later that same year, the painter produced Les promenades d’Euclide (Where Euclid Walked, 1955, in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts). As part of a letter dated October 3, 1955, he included a small posed photograph of himself seemingly in the middle of painting the picture (see above).

By 1962, the year of the last two letters in the group, Magritte’s tone had softened somewhat: he addresses Iolas as “cher ami” (dear friend), and, in one of them, thanks him for the gift of a bracelet, delivered to him by then-aspiring art historian Suzi Gablik. Magritte remarks that “it resembles the one that your sister Niki was wearing in Cannes. So Georgette [Magritte’s wife] and Niki will now be wearing the same bracelet.”

In addition to these revealing letters, other highlights of the Getty Research Institute’s Magritteana include letters to and from his close friend and co-conspirator Paul Colinet, many of them illustrated, as well as correspondence with writer and fellow Surrealist Marcel Lecomte. These letters include an exquisitely illustrated explanation by Magritte of French painter Edouard Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882), which presents his unique take on the famously enigmatic painting. Though his analysis makes much more sense for Manet’s preparatory oil sketch, Magritte dispenses with the mirror that forms part of the standard account of the painting, preferring instead to see doubles in a deep receding space. The interpretation is very literal, but also totally Magritte.

The new letters, along with the other Magritte holdings in the special collections, are accessible to researchers now.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.