In the 1920s, Lyonel Feininger was one of Germany’s best-known artists. He painted, drew, and made prints; he sketched caricatures and composed music; he even created a miniature city that would presage stop-motion animation. But in 1928, at age 58, he embarked on an entirely new artistic project: photography.

“Moholy’s Studio Window” around 10 p.m., Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), 1928. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 5 1/16 in. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The story of Feininger’s fascination with this new medium is told for the first time in the exhibition Lyonel Feininger: Photographs, 1928–1939, curated by Laura Muir of the Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, and opening today at the Getty Center.

Feininger was originally reluctant to take up photography, dismissing it as a “mechanical medium.” But he was lured by his neighbor, fellow Bauhaus master and photography pioneer László Moholy-Nagy, as well as the enthusiasm of his own sons Andreas and Theodore (nicknamed Lux), who installed a darkroom in the basement of their house.

Photography had, literally, arrived at Feininger’s doorstep.

Moholy-Nagy championed an approach to photography called the “new vision,” which encouraged using the camera to experience and reframe–not just depict–the world. “New vision was about expressing, not just documenting,” Virginia Heckert, curator of the presentation of the Feininger exhibition at the Getty, told me. “It enabled its makers to see the world differently.”

The techniques of new vision photographers were inventive and unorthodox: extreme close-ups, negative printing, and photograms (cameraless photography). Small box cameras were used to see the world from above and below and transform it through unusual angles.

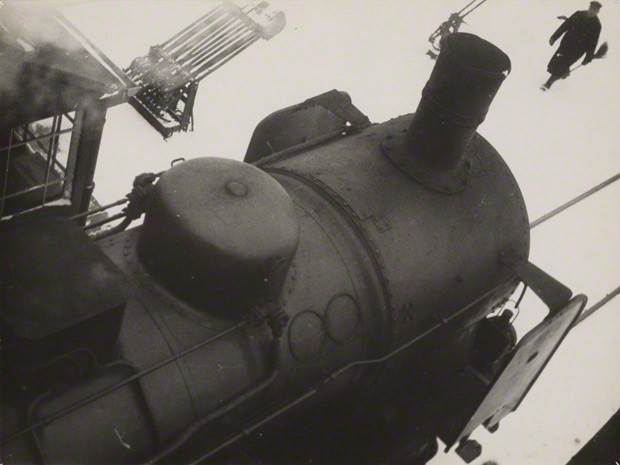

Feininger and his fellow new visionaries also experimented with extreme cropping, in which the entire context in a photograph is jettisoned, creating a tension between representation and abstraction and conveying immediacy and spontaneity, as seen in this photo of a locomotive in a train yard covered in snow, which seems both looming and playful.

Untitled (Train Station, Dessau), Lyonel Feininger, 1928–29. Gelatin silver print, 6 15/16 x 9 5/16 in. Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Feininger’s new vision was also full of dramatic darks and lights—perhaps not a surprise, since contrast was a frequent element in his paintings.

On a single night, March 26, 1929, he made an entire series of views of the Bauhaus building. Lugging his tripod, his new Voigtländer Bergheil camera (which you can see in the show), and a supply of glass negatives, he circled Walter Gropius’s famous building, taking photographs from different perspectives. The images capture bright halos of light against a dramatic foil of darkness.

Besides being partial to these dramatic effects, Feininger photographed at night for a practical reason: he painted during the day.

Bauhaus, Lyonel Feininger, March 26, 1929. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/16 x 9 7/16 in. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of T. Lux Feininger. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Feininger continued to experiment with photography throughout the 1930s and beyond, though it remained a highly personal part of his art. He never exhibited his photographs, and shared them only with family and a few friends. Intimate prints in the exhibition show family trips to the Baltic Coast, a tour through Brittany.

But perhaps the most intimate works of all are not the vacation snapshots, but rather Feininger’s series of mannequins in shop windows, in which enigmatic wax figures seem trapped in a prison of their own self-absorbed indifference.

Drunk with Beauty, Lyonel Feininger, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/16 x 9 7/16 in. Gift of T. Lux Feininger, Houghton Library, Harvard University. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Feininger created these unsettling images in late 1932 and early 1933, as Germany was being consumed by the National Socialists. Within four years, the Nazis would declare his art “degenerate” and prompt him to return to New York, where he had spent his first 16 years. Feininger would continue to photograph until his death in 1956, making more images unique for their arresting darkness and otherworldly light.

Fascinating story of Feininger’s career. Love the different perspective shown in these photos. Will have to see this exhibit!