Playing Florentine soccer, engraving in Giovanni de\’ Bardi, Discorso sopra il givoco del calcio fiorentino del Puro Accademico Alterato (Florence, Stamperia dei Giunti, 1580). The Getty Research Institute, 1370-871

The World Cup kicks off today in South Africa, and the international mania for soccer—sometimes known as “the beautiful game’’—put me in mind of one of the many interesting treasures held in the collections of the Getty Research Institute.

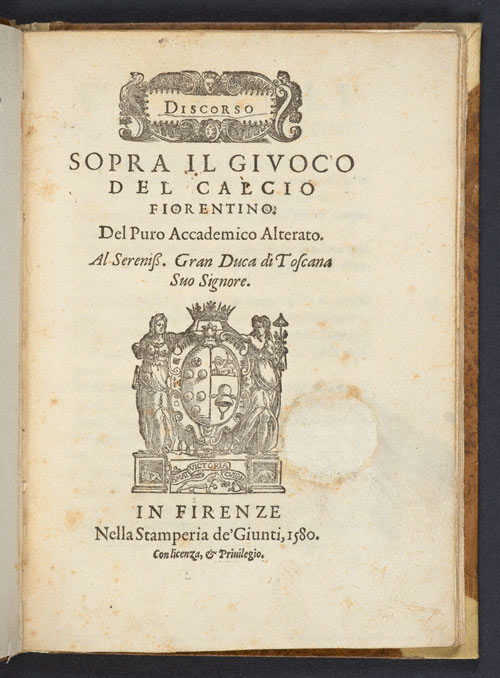

In 1580, an author using the pseudonym “Puro Accademico Alterato” published the Discorso sopra il givoco del calcio fiorentino (Discourse on the game of Florentine Soccer) that describes the game of calcio fiorentino or “Florentine soccer” as played by young aristocrats in the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence, Italy, between Epiphany and Lent in the Catholic calendar.

Dedicated to Francesco I de’ Medici, this early rule book bears little relation to FIFA’s Laws of the Game, founded on the Cambridge Rules of 1863. In early Florentine soccer, which resembles an elaborate mishmash of crude soccer and rugby moves with some added violence, there are 27 players per team of “gentlemen” aged 18 to 40 who must be good-looking and dressed in silk finery.

Players are free to use their hands if necessary—not only to handle the ball, but also to punch each other! Dirty in more ways than one, the game takes place in a huge sandy pit with a goal that stretches the width of the field at each end. Not surprisingly, the objective is to score more goals than the opposing team—with the complete freedom to shoulder-charge, kick, or trip adversaries in the process.

The writer of the soccer handbook, “Il Puro,” was Giovanni de’ Bardi, Count of Vernio (born Florence, 1534; died Rome, 1612), who created musical and dramatic entertainment for the Medici court. A member of learned societies such as the Accademia degi Alterati (Academy of Elevated Ones), he regularly hosted a group of noblemen and musicians at his house, including composers Vincenzo Galilei (father of the famed astronomer) and Giulio Caccini. Later known as the Camerata, the group discussed poetry and music focusing on ancient Greek music and its ability to communicate poetic texts so expressively.

Frontispiece of Giovanni de’ Bardi’s Discorso sopra il givoco del calcio fiorentino

The result? Their dramatic music experiments based on Greek tragedies led to a new style of monody (an emotional song composed for a single vocal part) that laid the foundation for the beginnings of Italian opera—a competitive sport with as much silk finery as Renaissance soccer, sans shoulder-charging.

Soccer and opera occasionally cross paths to this day: Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti, who was once an avid soccer player himself, performed Giacomo Puccini’s “Nessun Dorma” from Turandot at the 1990 World Cup in Italy. His rendition instantly achieved global pop-like status, and Puccini’s aria remains an anthem for world soccer.

Thanks, for the brief soccer history lesson. I consider myself a soccer connoisseur and I didn’t know that they used to play with those rules.

Apparently the game was revived and is now played as part of festival tradition. There is a documentary on youtube about it but this slideshow has images and some descriptions that show just how close it is to the game as described in “Discorso sopra il givoco del calcio fiorentino”. Really fascinating stuff.

http://www.environmentalgraffiti.com/featured/calcio-fiorentino-manliest-game-on-earth/9859