Sketchbook from September 5, 1985, with cover painted by Otto Muehl. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Austrian artist Otto Muehl is best known as the co-founder of Viennese Actionism, a short but “violent” movement in 1960s Vienna that sought to develop an action based art. Muehl’s so-called Material Actions—in which the human body and the site of art-making were the surfaces for the production of art—were a radical departure from an object-based conception of art. Muehl was also the mastermind behind the controversial living experiment called Actionanalytische-Organisation (AAO), also known as the Friedrichshof Commune.

Born in Austria in 1925, Muehl passed away in Portugal on May 26, 2013, just a few weeks before I finished my work on his archive at the Getty Research Institute.

The archive includes rare photographic material documenting Viennese Actionism and Action Analysis sessions at the Friedrichshof Commune and a wealth of Muehl’s unpublished writings, but at its core are approximately 165 sketchbooks dating from 1979 to 1997, the time when Muehl withdrew from Action Art and returned to traditional drawing and painting.

Sketchbooks with covers painted by Otto Muehl. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Most of his sketches are executed in black ink or watercolor; some are executed in pencil. They not only testify to Muehl’s remarkable artistic ability as a draftsman and painter, but also reveal his interest in a wide range of topics. Muehl’s main focus is the dynamic movement of human and animal bodies. Many of his sketches are erotic, some are strongly sexualized, and some are studies of various movements, such as a series showing a figure vigorously playing piano. The intense and frequently transgressive nature of the sketches suggests that, for Muehl, the process of drawing and painting played a critical role in exploring human obsessions. There are also discerning studies of intense facial features, merciless caricatures of Nazi and Soviet figures and contemporary German and Austrian politicians, scenes of World War II atrocities, and even traditional religious topics such as the Temptation of Christ.

The sketchbooks from the early 1980s are profusely annotated and primarily concern the theory of painting and the creative process in general. They also include commentary and formal analysis of art by other artists and philosophical reflections on Muehl’s own art and life. Most frequently, he writes about Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, and draws his own renditions of their artwork. There are numerous sketches after works by Picasso, such as a running woman (below), and after Cézanne’s landscapes and portraits, such as a self-portrait (further below). Muehl’s sketches after other artists’ works reveal his exceptional ability to study their styles and to produce versions that are not copies, but rather his own statements in form and color about their art.

Otto Muehl after Pablo Picasso, 1979. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Otto Muehl after Paul Cézanne, 1983. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

In his sketchbooks, Muehl also comments on contemporary artists and analyzes their art. In 1979, he wrote extensively about German artist Joseph Beuys, who then was already regarded as one of the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century.

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1979, with notes on Joseph Beuys and a German press clipping reading “Amerika entdeckt ihn” (“America discovers him”). The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

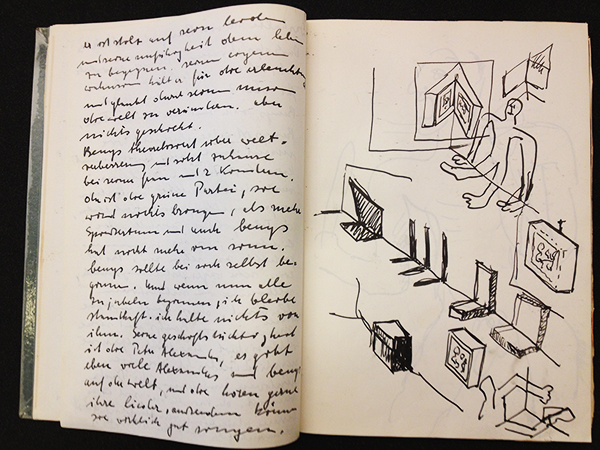

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1979, with further notes on Joseph Beuys and drawing of an installation by Beuys. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

In the note shown above, Muehl criticizes Beuys’s prominence in contemporary art scene: “Was halte ich von Beuys? Nichts. Dass das Phenomenon Beuys möglich ist, ist ein schlechtes Zeichen für den Zustand unserer Welt.” (What do I think of Beuys? Not much. The fact that a phenomenon like Beuys is possible is a sign that our world is in bad shape).

Another example of Muehl’s preoccupation with Beuys is his drawing after Beuys’s famous object Der Fettstuhl (The Fat Chair). Contrary to Beuys, whose artworks are often referred to as “ugly anti-images,” Muehl drew the Fat Chair in cheerful bright colors, placing it opposite an identical but smaller picture of the chair, framed and hung on the wall. Muehl’s Fat Chair is not an “ugly anti-image” but a pretty object in traditional museum setting. In 1986, the year Beuys passed away, Muehl drew a portrait of Beuys on the front cover of one of his sketchbooks.

Otto Muehl after Joseph Beuys’s Fat Chair, 1979. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

The majority of Muehl’s sketches are executed in his own distinct formal style: intensely colored faces (below), women in red and black (further below). Muehl’s lines flow delicately, but his colors are bold and bright.

Often, Muehl’s sketches are formal and thematic references to his Material Actions from the time of Viennese Actionism during the 1960s. Material Actions—which included naked bodies, blood, public urination and defecation, staged self-mutilation, and killing of animals—was highly transgressive, and scandalized the Austrian public. During the 1980s, Muehl frequently painted female nudes accentuated with bright blood red, reminiscent of the nudes covered with blood that formed part of the Material Actions. Another reference to Viennese Actionism is the human face painted on one of the sketchbooks’ covers, shown at the top of this article. The distortion of facial features with black paint recalls staged self-mutilation and other physically abusive actions Muehl performed. The sketches are an unexplored resource for the study of continuity and change in his artistic imagery.

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1983, with colorful faces. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1984, with woman in red, 1984. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1985, with woman. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Otto Muehl sketchbook, 1985, with two women. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

In addition to these sketchbooks, also now available for research are more than 1,000 negatives and contact sheets of Viennese Actionist events from the 1960s, numerous scripts for Material Actions illustrated with drawings, letters rich in detail about the performances and their controversial reception, and legal documents relating to court proceedings against Muehl and other participants of Viennese Actionism.

Unpublished writings about Action Analysis and fragment of a handwritten script for a Material Action. The Getty Research Institute, Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997

Available for the first time are also approximately 300 writings dating predominantly from the 1970s, when Muehl was active as a painter and teacher within the community of Friedrichshof. By 1970, Muehl had withdrawn from performing Material Actions and developed the idea of artistic and therapeutic self-expression, which he called Action Analysis. His writings reflect the transition from the concept of art as action to life as art and social change. At Friedrichshof, Muehl wrote profusely on a wide range of topics, from the role of the artist in the commune to criticism of state authority and the need for revolution, world peace, psychoanalysis, homosexuality, sex, gender relations, traditional marriage, and raising children. His declared aim was a new model for society based on the principles of free sexuality, common property, and collective education of children, and the destruction of, what he saw as, bourgeois concepts of marriage and private property.

The Otto Muehl archive, with its unpublished photographs, writings, and sketchbooks, opens the way to trace and study changes as well as continuity in Otto Muehl’s art making from the conceptual approach, to art as action and life as artistic self-expression, to self-realization as an artist and teacher through traditional drawing and painting. More broadly, it will assist scholars in exploring the changing focus in postwar Europe.

The completed finding aid to the papers is available here.

See all posts in this series »

Why is Otto Muehl’s conviction for child sexual abuse in 1991, for 7 years in Austria not mentioned ?

Do you and Getty condone paedophilia ?

A very surprised reader..

Leon

Thanks for taking the time to comment. It is true that Otto Muehl was convicted of sexual offenses with minors and of drug crimes, and we probably should have included that information for readers unfamiliar with him. This piece focuses on the contents of the archive at the Getty Research Institute, which don’t contain material related to these cases.

Hello. I possess several publications (newspapers and books) from and about the AAO. Also one unpublished book ‘Die wilden 60er Jahre’ (bound photocopie) as well as one longplay Vinyle record in which Muehl is singing. Would the Getty be the place where my stuff would be made accessible for research into Muehls community experiment, or are you strictly limited to his paintings. I am looking for the right place to donate this stuff to. Thanks for taking the time to answer.

Andreas Roellinghoff, Rte. de Genève 60A, CH-1028 Préverenges, +41 21 803 58 00