New tools will help scholars reveal the yet-untold stories contained in art dealers’ records at the Getty Research Institute

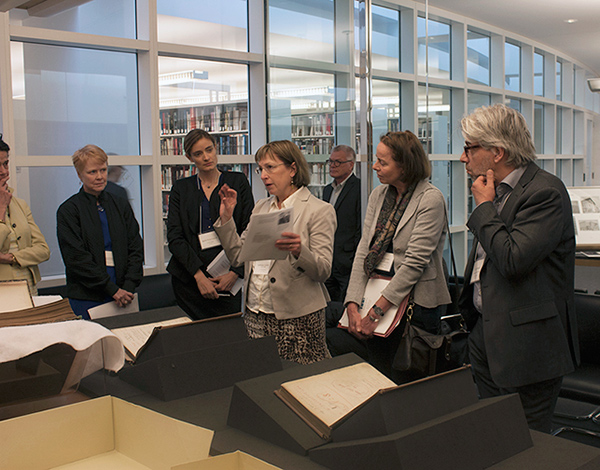

In the Special Collections Reading Room, workshop participants look inside an art dealer’s photograph album. Foreground, left to right: independent scholar Decourcy McIntosh, Research Institute director Thomas Gaehtgens, and associate director Gail Feigenbaum.

Inspired by our recent acquisition of the Knoedler Gallery archives, the Getty Research Institute held a workshop in May to consider how we could best make art dealers’ archives accessible to scholars, and useful for their research.

Our holdings—which also include archives of the Duveen Brothers, Goupil & Cie, and other prominent art dealers who profoundly shaped the art market—make the Research Institute a premier center for studying the art market in the Gilded Age. Literally thousands of linear feet of business records provide the evidence that will allow scholars to rewrite American art and cultural history, including the formation of our art museums.

The amplitude of these archives is both a blessing and a challenge. They encompass far more material than one scholar working alone can digest. We have begun to use technology to facilitate collaboration, but we must do more. That is why we invited our colleagues to think about how to move forward.

Kathleen Curran, professor of fine arts at Trinity College, speaks to workshop participants

Workshop participants were leaders of international institutions with related archives, including the National Gallery in London, Colnaghi’s at Waddesdon Manor under the patronage of Baron Rothschild, the Netherlands Institute for Art History, the Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Villa I Tatti, the Frick, the National Gallery of Art’s Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, and The Huntington. Curators, scholars, and the president of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation also attended.

Discussions ranged widely, but two principal areas of interest emerged.

Bringing Art History into the Digital Age

Art dealers relied on stock books like this one to keep track of inventory, often using codes to hide the names of purchasers and prices. Digital tools will help process and interpret this vast pool of information. Here, a stock book from Boussod, Valadon, & Co., dated to 1891–95.

The first theme was how to achieve what one participant called “the gentle art of combining and sharing art historical data.” Art dealers were actors in an international context, working together across the Atlantic; buying and selling to and from many of the same people (often the same objects) from China or from the aristocratic houses of England, France, and Italy; vetted by the same experts; and restored by the same conservators.

The key to mapping these dynamic networks is the stock book, which registers each object in a gallery’s inventory with a stock or accession number. Thanks to a grant from the Kress Foundation, we are building a database of the Knoedler and Duveen stock books, modeled on the one we designed for the Goupil archive. We discussed how to coordinate efforts with our partners and invent ways to search across our interlinked repositories. At its core, this is a digital art history project, and managing our data and imaging in a way that makes these archives useful to researchers is a primary concern.

Writing the Art Market Back into Art History

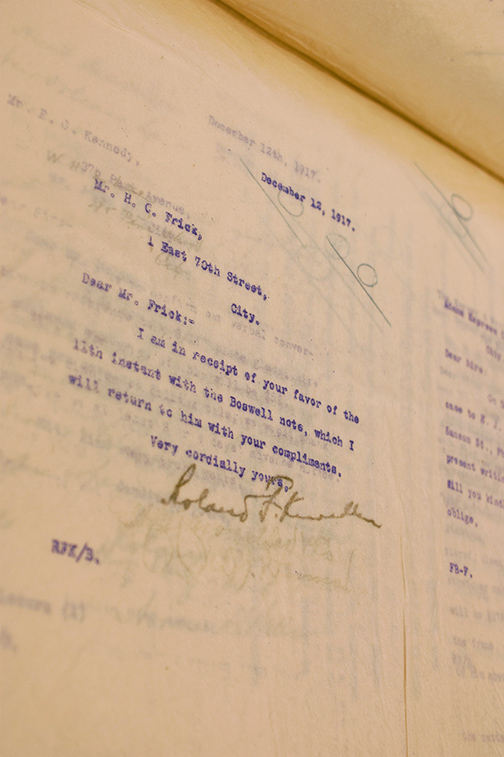

Letters between art dealers and important clients are key documents of art history. Here, a letter from dealer Roland Knoedler to collector Henry C. Frick.

The second major area of mutual interest we identified during the workshop was the importance of approaching the dealer archive as a tool of art historical understanding. Two economic historians shared crucial methodological insights into analyzing business records. Many of our big questions, however, led us back to the overarching observation that the art market has been written out of the history of art history. It was in the art market, especially in the U.S, that expertise developed for museums and the discipline of art history. On discovering a contract between firms which stipulates that one agrees to promote in America the French style in which the other happens to specialize, we see that we have barely begun to fathom the dealer’s role in generating “taste”, and in steering the great age of American collecting. In the names of their clients—Frick, Kress, Mellon, Morgan, Walters, Widener—we recognize the cultural philanthropy that undergirds the formation of the American art museum.

We will be working on these two major needs—harnessing technology to analyze statistics and map patterns, and recuperating the art market as a crucial factor in art history—as we continue to make the Knoedler Archive, and indeed all of the Getty Research Institute’s collections, more accessible to the scholars who use them in their work.

Comments on this post are now closed.