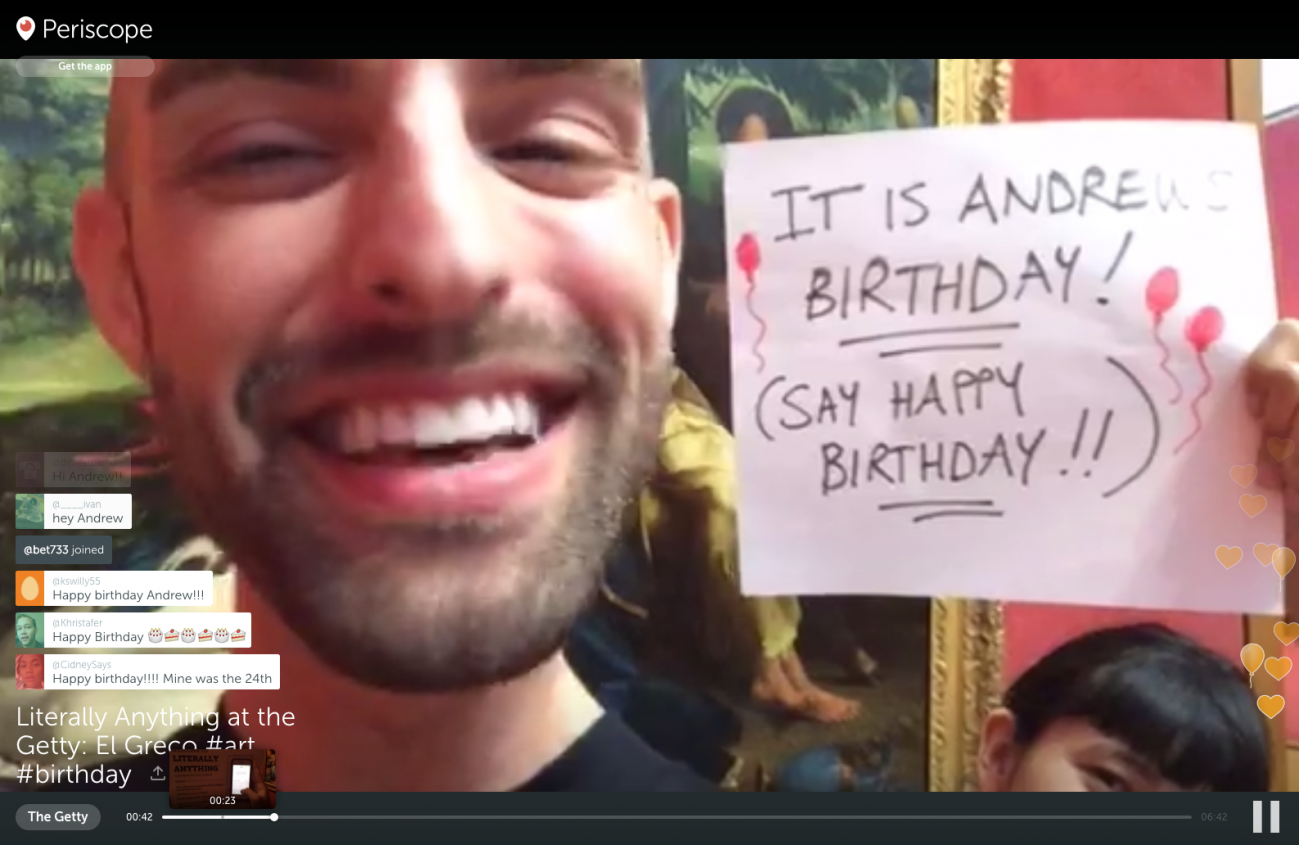

All this year, teams at the Getty have been experimenting with live video using Periscope and Facebook Live. The three of us have focused on Periscope, broadcasting from the galleries every Tuesday at noon. Hosted by educator Andrew Westover, our show, #LiterallyAnything, is a five-minute live-video broadcast where everyone is encouraged to ask literally any question, make literally any comment about a single artwork.

Unfortunately for us (but joyfully for him), Andrew leaves the Getty this week to pursue his PhD in education and ethics at Harvard. We’re looking forward to creating new live-video ideas, and we’re really eager to learn what you would like to see. Where can we take you? What can we chat about? We’d love to hear your thoughts. Jump to the poll at the bottom of this post to weigh in!

LIVE on #Periscope: Literally Anything at the Getty: Replica Cave 285 (Cave Temples of Dunhuang) #art https://t.co/vvitjy6ChW

— The Getty (@thegetty) July 5, 2016

In this post we’ll share why we did the show, what we learned doing it, and some of our biggest wins and fails.

#LiterallyAnything, a Show about…Literally Anything

#LiterallyAnything grew out of our desire to create a digital space for irreverent, empathic human interaction around art. Irreverence is important to us—not because we want to make fun of art (we don’t), but because we want to make it genuinely enjoyable and accessible, without fear of asking a “dumb” question or saying the “wrong” thing. There’s no one right or smart way to talk about art, and we wanted our show to reflect that.

#LiterallyAnything was hatched as part of Culture24’s annual Let’s Get Real project, which we took part in. Let’s Get Real brings workers from cultural organizations together to think about what we’re doing online, whether it meets user needs, and how we can work better across internal silos. Each team creates an experiment as a test case for collaboration and user focus, and Periscope was our experiment. (Download the full Let’s Get Real 4 report here—it’s packed with juicy details on all the participating organizations’ experiments.)

We started planning the show in October 2015, before Facebook Live was available for pages—see the Getty Museum’s Facebook page for some great recent experiments with this slightly different medium.

Why a “Show”?

We chose a show concept—same time, format, and host each week—to create a memorable schedule for viewers and to give ourselves a clear focus. We were also hoping that a show would help viewers remember when to tune in and get to feel comfortable with our host (Andrew), both of which happened surprisingly quickly.

Our target audience was millennials in the U.S. and Europe without extensive art knowledge; our goal was to create a lively, fun, casual approach to connecting with individual artworks. Broadcasts would be fast, just five minutes, to prevent slipping into lecture mode or artspeak, and to keep energy high. We’d feature the same host each week to provide consistency, personality, and a conversational tone.

Behind the scenes, the show concept also helped us manage two real-world constraints:

- Having a fixed schedule helped us break through planning-meeting-itis and create a productive rhythm. This advice came to us our courtesy of Matt Locke, our Let’s Get Real project advisor, who encouraged us to become aware of and break our entrenched rhythms, such as the well-known curse of “the discussion meeting whose sole outcome is another discussion meeting.”

- Live video has technical and human limitations. We played with other ideas for Periscope—we loved the idea of choose-your-own-adventure walkabouts, for example—but they had too many challenges. WiFi isn’t consistent (our terrain is complex), loaned and copyrighted artwork lurk everywhere, and we need to make sure that visitors, especially minors, don’t appear on camera without consent. Having a one-artwork show format made the best of these constraints.

Creating a Born-Digital Scope

Why not just broadcast an existing tour? Live-streaming is a great medium for extending access to on-site events, but Periscope isn’t a good fit for talks and gallery tours: it’s hard to hear, hard to connect with (or sometimes even see) the speaker, and nearly impossible to participate.

It was important to us to create a Periscope-native experience, one that made full use of the tool’s features, embraced the social norms of the platform, and matched the interests of its user base. We also wanted our audience’s interests to help guide the content, so we established a weekly Twitter poll where our audiences could vote for what interested them most.

Most weeks, we used a poll to invite people to pick between two artworks. Emoji polls, as opposed to straight text, often received more engagement.

We didn’t want to aim a camera at an expert standing in front of an artwork, a familiar museum video model but one that many innovative institutions are breaking away from. Phone video now makes it possible for expert and cameraperson to be one and the same, bringing a new intimacy to the encounter between art and audience.

So what would a Periscope-native art encounter look like? It would be visual, intimate, interactive, and short. The host would speak directly to viewers in a personal way, but wouldn’t be on camera much; the art would take center stage. By moving the camera across the artwork, Andrew was able to show the work as he sees it (Periscope’s slogan is “Discover the world through someone else’s eyes”) and call attention to details we might otherwise miss.

There was an unexpected plus to this approach, too: we were lucky to team up with an expert curator every few weeks as co-host, and several of them appreciated the opportunity to talk about art without being on camera.

Wins and Fails

Every week a new issue sparked a new fix—echoey spaces, uneven WiFi, loud background noise, baffled visitors—but week after week, the show became smoother to run, and we become more comfortable solving problems on the fly. Some of our fixes:

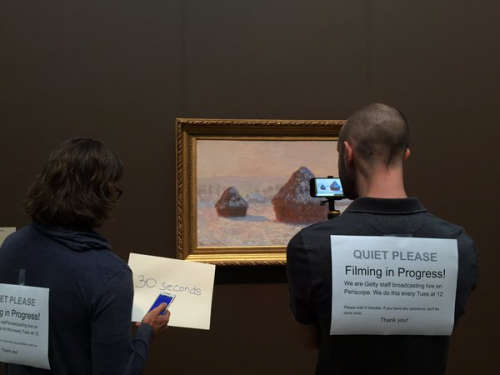

Andrew scoping with senior media producer Christopher Sprinkle (left), both wearing our improvised signs.

- Cue cards. Prompts really help when you’re trying to narrate, respond to on-screen questions, focus the camera, and remember a bunch of art historical facts. The most useful cue card was the one we made for the halfway mark, when Andrew would remind people who’d just tuned in where they were and what they were looking at.

- A 30-second countdown. We created a welcome card and started each show with a timed 30-second countdown, when Andrew could welcome and banter with viewers as they joined. We started with 60 seconds, but this felt a little too long; 30 was about right.

- Signs taped to our backs. These simple laser-printed signs helped staff and visitors understand what we were up to, and assure them that we’d be out of their way in minutes.

- A backchannel host. As our viewership rose, more and more questions flashed across the screen. It helped to have one of the team members watch the show while logged in as the Getty, to answer basic questions that Andrew had already addressed. (The most frequent questions were the artwork’s date, its size, the artist’s name, and the location of the Getty.)

- Faux labels. A few broadcasts showed artwork with copyright restrictions. There’s no post-production in live video, so we created a handmade object label with a full caption and copyright line, which Andrew held up to the camera.

- Basic gear: gimbal and mics. We invested in a smartphone gimbal, which holds the phone in a mount and stabilizes it against shaking. We’ve been happy with the Ikan Fly-X3-Plus, though it only holds the phone in landscape mode and shakes like crazy if you aim at the floor or ceiling. We also got two iPhone lavalier microphones, which make a huge difference in cavernous gallery spaces or when there’s background noise (hi there, school groups!). We have the RØDE smartLav+ plus a cheap splitter cable for times when we have a guest expert.

- A small team with specific roles. To manage a fast-moving, weekly, ever-changing show, we found that a team of three can get the job done. All we needed? Andrew (the host), a dual time-keeper/cue-card operator, and the backchannel moderator. Each person is responsible for one task, and we had a few staff trained and ready to step in if needed.

Another win was reaching out to our fabulous ITS networking team, who pitched in with WiFi tips and solutions. And a big boost we can take zero credit for—the kind folks at Periscope (and its parent company, Twitter) helped us with advice on strategy and execution and featured three of our broadcasts within the app. Two of them received over 100,000 views in 24 hours. Thanks, @periscopeco!

What We Learned

Inspiring interaction is harder than it seems. Here’s a recipe of what worked for us:

- Establish an open, safe space. Be warm and genuinely curious about viewers. Simply calling for questions isn’t enough to incite discussion. Safety and openness have to be established over time, by consistently acknowledging all kinds of questions and comments, including jokes, “stupid” questions, and emojis, and by repeating back and validating comments. Ask where everybody is from, remember and acknowledge repeat viewers week to week, warmly welcome people to the broadcast using their handles, and smile. We even featured a viewer who was in town from London on a broadcast, and he wrote about the experience on this blog. (This was such a treat, and one of the happiest days we’ve had on the job.) In short, do more than just invite the audience to be participants—make sure they know you actively desire their participation.

- Be joyful. Have humor. Excitement is contagious. Talk about your subject in a loving, positive way. Jokes can break down the barriers of old master art to humanize complex allegorical or mythological concepts (or any technical material, for that matter). Self-deprecation works, too!

- Bring the fun facts. Before every broadcast, Andrew would brush up on the chosen object, speaking with other gallery teachers, perusing the curatorial files, etc. He came armed with facts about the artwork—but not just any facts. To be contagiously interesting, facts must be surprising, memorably specific, and able to establish a human connection across time to the artist, subject, or place.

- Develop hosting skills. Being a great host mixes social skills, technology skills, and subject-matter expertise. If you want to go with a hosted show, be honest about skill sets and give yourself time for training. Theater and improv skills help (there’s a reason Museum Hack hires tour guides who have acting or comedy experience). Also, be okay with silence! It can take time for people to process and type, so providing several seconds for responses (rather than immediately jumping to a new question or comment) can create more space for conversation. Being a host is a performance, and requires the ability to dialogue and problem-solve quickly, gracefully, and with humor.

- DIY is okay. We used handmade signs and were transparent with our mistakes. “Oops, sorry our WiFi was too poor to continue in this room, that’s why we restarted in this other gallery!” Just explain; people get it and don’t mind.

As we get ready to plan our next experiments, we would love to hear from you. What would you like to see in a future art scope? We’d be thrilled to hear your ideas here or on Twitter.

A little more history of the artist as well as the interesting issues with the art piece.

Andrew did a great job, but don’t stop there.

Although Andrew is leaving, I hope the Getty will continue to broadcast in Literally Anything’s spot. Guest curator’s such as Bryan Keene were a real treat and I would love to hear/see more of his fascinating work with manuscripts. I would also like more focus on the beautiful antiquities in the collection. Lastly, I think 7 or 8 minutes would give time to address the basic information about each work AND give time to look closely at the details. Kudos to the whole team!!

Thank you, Stacey! We will be trying some experiments over the next few Tuesdays, some wacky, some serious, some TBD… Hope you tune in, we’d love your feedback and input to make sure we are creating things that are useful, joyful, and fun 🙂