When I was six years old, I decided there were two things I wanted to do when I grew up: write books—books that kids like me would read—and live in France. Three years later at summer camp, I began to learn how to weave on a low-warp loom. I returned home full of excitement over this age-old yet new-to-me art form, and I couldn’t believe my luck when my mom told me that she already had a loom and would save it for me.

As a toddler, I had played in my father’s art studio, using a wood frame as the opening to my imaginary dog house while pretending to be a puppy. I pieced together these memories and realized the frame was actually part of the loom, which had later been moved to storage.

After eight years of French classes and more summer camps, my mother took me to Paris. We wandered all over the city, and I practiced my timid French on a patient hotel concierge. The next time we returned, I had the addition of a high school French class; my voice was bolder, my footsteps more sure. In college, I studied abroad in Aix-en-Provence and Paris, falling in love with both cities, the art history course that led me through museums and churches, and the two French families who took me under their wings. I was so deeply entrenched that I began to dream in French.

Then I grew up.

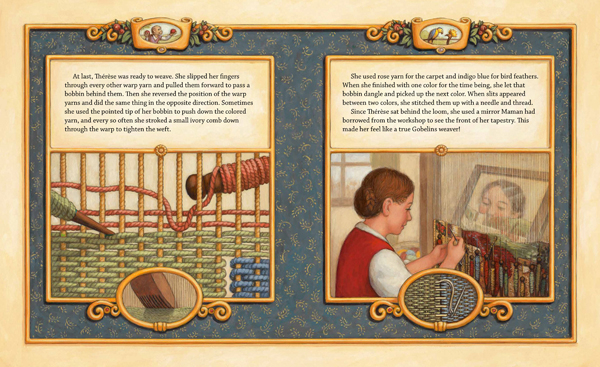

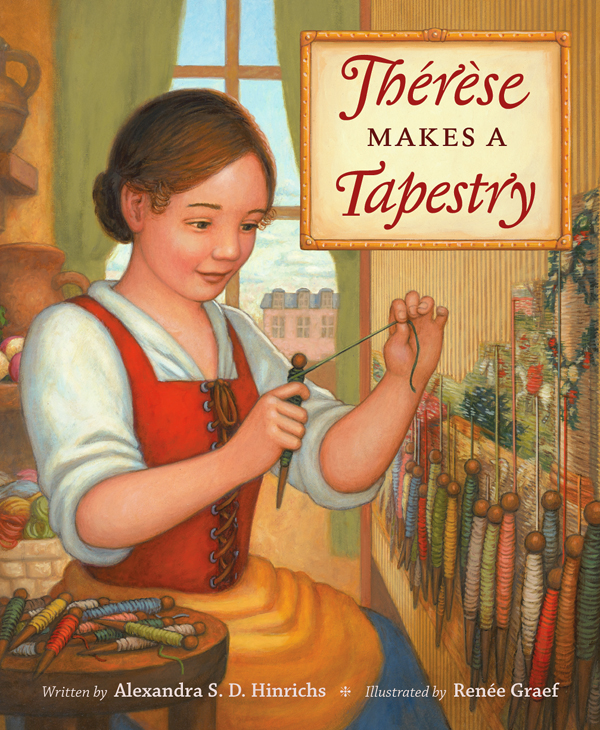

Grad school, multiple simultaneous jobs, and the birth of my first son all dulled some of the shine off my author dreams. When the Getty approached me to write a book about a girl who wove tapestries in 17th-century France, I realized that both the timing and the content suited me perfectly. Maybe because I had lost some of the confidence that I would be able to write and publish a children’s book, it was a breath of fresh air to imagine a young woman who has her own goal in mind and doesn’t waste any time making it happen. The result is the new book Thérèse Makes a Tapestry.

Discovering Gobelins

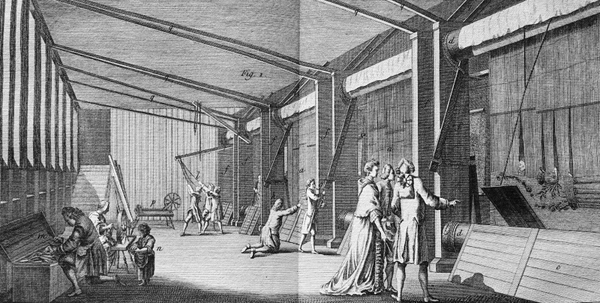

I began by researching the history of French textiles. It didn’t take long to decide on the story’s setting: the Gobelins Manufactory. The history of this tapestry factory fascinated me, especially because the weavers and their families lived on site. I was curious to find out whether children were present in the workshops. An image from Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie provided an answer.

A high-warp weaving workshop in the Gobelins Manufactory. From the 18th-century Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot

The print features a high-warp weaving workshop in Gobelins, and a young girl stands next to the man kneeling in the foreground. Lest there be any doubt about her role, Diderot’s legend denotes that the figure marked “n” is an “enfant occupé à porter les écheveaux,” which translates as a “child carrying skeins.” In other words, this girl has a job in the workshop. She sparked my imagination and led me to create my protagonist, Thérèse. In the opening illustration of the book (shown below minus text), Thérèse is positioned in a similar place as the young girl from Diderot’s image.

Studying Childhood

The concept of childhood and the role of children in society have changed over time. Philippe Ariès’s Centuries of Childhood, originally published in France in 1960 as L’enfant et la vie familiale sous l’Ancien Régime, is the book famous for launching the history of childhood as a field of study.

Ariès argued that childhood as a concept emerged around the 17th century—the era when Thérèse would have been born. His study established a framework for historians to debate and discuss this phase of life. When did adults recognize childhood? How have they defined childhood? How have those definitions changed over time and across cultures? Some historians have taken different paths by studying children themselves and looking at childhood as a culture, through the eyes of children.

Of course, even before they were formally studied, children have always existed. Every adult was once a child. So how do we study this fleeting stage of life? I love historical fiction because it acts as a window into some of these issues, bringing new questions to surface and offering possible, sometimes playful answers.

Imagining Thérèse

As I wrote Thérèse’s story, I asked the following questions: What would a child who lived among artists in a workshop setting do on a day-to-day basis? What if the child was a girl? Would she learn to weave even if she could never become a master weaver? What might her ambitions and dreams look like? What would she see, hear, smell, and taste? How did families express affection? How would she overcome the obstacles presented by the nature of her age and gender?

Some of the best sources of information for my research were the tapestries themselves. For example, a tapestry designed by Charles Le Brun depicts King Louis XIV’s historic visit to the Gobelins Manufactory in 1667. The tapestry features details that I used, such as the display of artworks outdoors in natural light. It also captures a compelling story, expressing the excitement, bustle, anxiety, physical labor, chaos, and hope of a memorable moment in time.

Louis XIV Visiting the Gobelins Factory, 1673, Charles Le Brun. Tapestry, 370 x 576 cm. Musée National du Château, Versailles

Bringing Thérèse to Life

Over the course of her story, Thérèse doesn’t waiver in her efforts, and she reaches out to others for support. Like making a tapestry, the creation of an illustrated book, particularly one of historical fiction, is a collaborative work. I was lucky to be a part of an invested, caring team.

Illustrator Renée Graef brought Thérèse and her world to life in such warm, vibrant tones. I grew up knowing and admiring Graef’s illustrations from the original Kirsten books of the American Girl series. I felt star-struck! In this video you can get a peek into the process as Renee brings a sketch of Thérèse to life.

Members of the Getty staff also worked tirelessly to bring the book together, including editor Elizabeth Nicholson, French decorative arts curator Charissa Bremer-David, and designer Jim Drobka.

At the exhibition opening for Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV at the J. Paul Getty Museum, I met everyone in person and together we celebrated Thérèse and the gorgeous tapestries on display that inspired her story. Walking through the exhibition, I loved seeing so many stories told in textile, and I couldn’t help but think of all the stories yet to come.

Charissa Bremer-David, Alexandra Hinrichs (that’s me), Renée Graef, and Elizabeth Nicholson in front of the tapestry Château of Monceaux/Month of December, designed by Charles Le Brun and created at Gobelins, France, before 1712. It is one of two versions hanging in the exhibition Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV. The design inspired the tapestry Thérèse weaves in Thérèse Makes a Tapestry. Photo: Bruce R. Dean

Text of this post © Alexandra Hinrichs. All rights reserved.

Thank you for sharing the behind-the-scenes making of this lovely book, a true work of art! ( I loved the Kirsten books, too!)