Paleographers at work: Participants in the Mellon Summer Institute in French Paleography at the Getty Research Institute decode a 14th-century manuscript on chess.

Paleography is the study of old handwriting. Paleographers are specialists who decipher, localize, date, and edit ancient and medieval texts—those written by hand, before the advent of print—making them available for others to read and understand.

I’m a doctoral student at UCLA in Indo-European Studies and a philologist. My specialty is studying the changes that have occurred over the centuries in Latin and French. I’m also working on the catalogues of the UCLA manuscript collections, in collaboration with UCLA’s Center for Primary Research and Training and the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. The catalogues I’m helping to prepare are essential in making known to outside researchers what may be of interest to their work in UCLA’s collections. In both of areas of my work, my paleography skills are constantly put to the test.

I was delighted to be a participant in the just-concluded Mellon Summer Institute in French Paleography, which taught scholars from a variety of disciplines the skills we need to read documents from a specific time and place: France in the Middle Ages. Most of my colleagues at the Summer Institute were there to acquire proficiency in reading medieval sources directly, straight from the manuscripts, for the purposes of their own historical, linguistic, or literary research. During the course we consulted many volumes from the Getty Museum’s collection of medieval manuscripts, which is particularly rich in French examples.

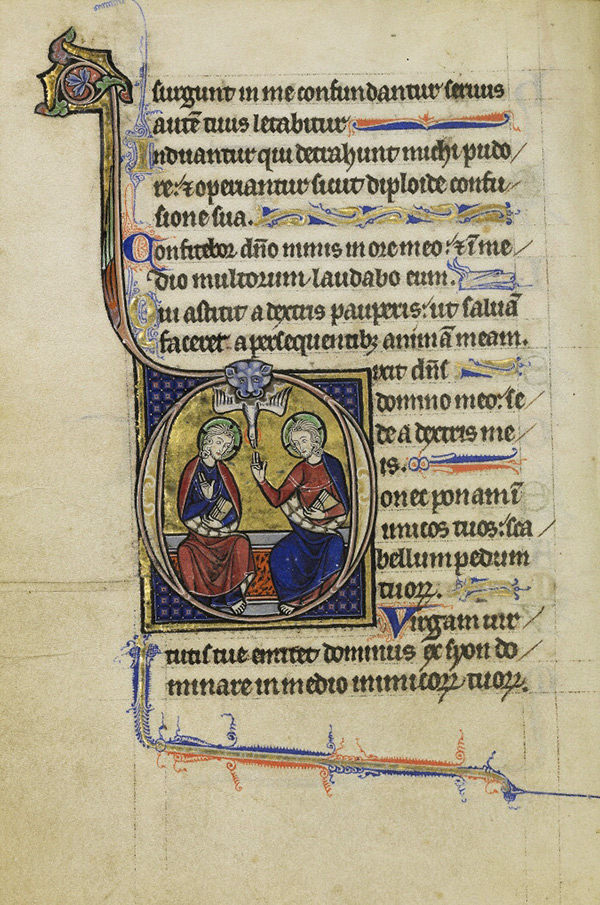

Page in the Wenceslaus Psalter, about 1250–60, French, unknown illuminator and scribe. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 9/16 x 5 1/4 in.

Why Paleography Requires Skill and Practice

Even though we have ancient and medieval documents at the ready, nicely preserved in museums, archives, university holdings and libraries, they do require an immense amount of specialist work to be made to “speak up.” Here’s what that work entails.

Learning Historical Dialects. To read texts written in old languages, such as Old French, requires knowledge of their grammar, syntax, dialectical variants, and more. Paleographers must master several foreign languages, historic and modern, to do their work.

Deciphering Writing Systems. In addition to being written in what amounts to a foreign language, medieval texts are encoded in a system of writing that is strange to the modern eye. Even when a language retains the same alphabet, letter shapes evolve. Twelfth-century handwriting does not look the same as 16th-century handwriting, and both would certainly be very different from what a 21st-century writer would pen down.

Mastering Archaic Abbreviations. Complicating this picture further, the medieval period made use of complex systems of abbreviations and ligatures (letters joined together) that varied, even within a given time period and place, from genre to genre. For instance, legal practice had its own specialised language. This medieval “legalese” not only made use of its own jargon and turns of phrase, but also of its very own system of abbreviation. Legal language was as obtuse then as it is now to the untrained reader!

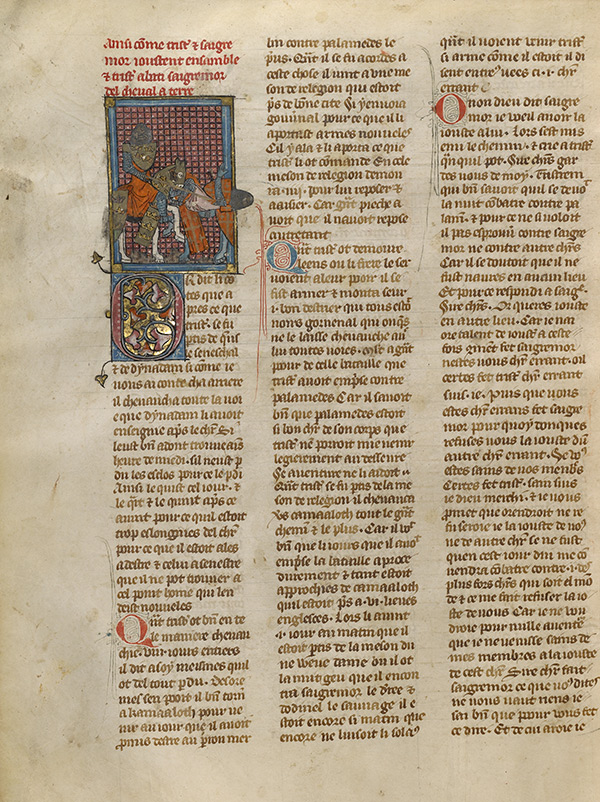

Page in Roman du Bon Chevalier Tristan, Fils au Bon Roy about 1320–40, French, unknown scribe; Jeanne de Montbaston, illuminator. Tempera colors, gold paint, and silver and gold leaf on parchment, 15 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 5, fol. 332v

Why Paleography Matters

Once they have learned all these things (and practiced them again and again), paleographers are ready to make a major contribution to scholarship in many different disciplines.

Helping Illuminate Language Change. Ancient documents are the witnesses we have of the small changes that have occurred over a language’s history, affecting its pronunciation, its grammar, and its vocabulary. If you’ve ever read the King James Bible, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, or (especially) Beowulf, you’ve seen that languages evolve. Modern languages, such as French and English, are very far removed from their medieval counterparts—at least to the uninitiated. Studying old documents, and comparing them over time, is key to understanding how language has changed over the centuries.

Making Primary Sources Available. The data contained in ancient and medieval documents—literary data, historical data, and economic data, just to name three—is the starting point of the work of historians, art and music historians, specialists of ancient languages, literature specialists, literary critics, and linguists. Paleographers must first decode this data to make it useful for others to study.

Editing Ancient Documents for Publishing. There’s one last task paleographers perform, and it’s one of wide-reaching importance. They make ancient documents available to the rest of the scholarly community and to the public through editions. If you think of the works of Shakespeare, you might think about a bound paperback, neatly printed. Yet paleographers (and indeed hordes of paleographers, in the case of Shakespeare!) have read the handwritten manuscripts of his plays and fought over how to best recover the original text. Without these crucial editions, an ancient text would remain accessible only to a handful of specialists, who must work their way through the barriers of language, material decay, and ancient writing systems to recover the voices of those who wrote these documents long ago and far away.

Page in Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César, about 1390–1400, French, unknown scribe; First Master of Bible Historiale of Jean de Berry, illuminator. Tempera colors, colored washes, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 14 15/16 x 11 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 3, leaf 2

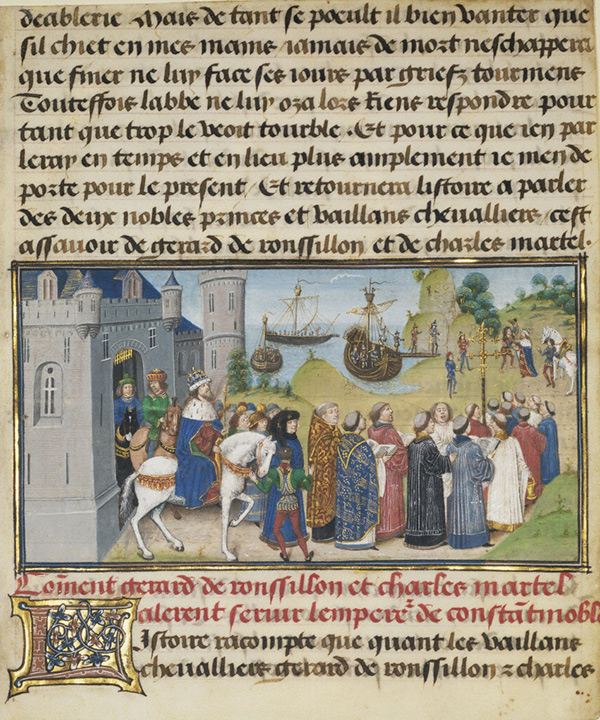

Page in Histoire de Charles Martel, French, written 1463–65 by an unknown scribe; illuminated 1467–72 by Loyset Liédet and Pol Fruit. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 9 1/8 x 7 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 6, leaf 2

Text of this post © Éloïse Lemay. All rights reserved.

Greetings,

It would be good if you could explain the differences between the various kinds of editions: critical edition, diplomatic edition, paleographic edition, semi-paleographic edition, and any others there many be. To highlight the differences, it would be good to take a few lines of a text and transcribe it critically, diplomatically, paleographically, semi-paleographically, and so on.

Best wishes,

David L. Gold

Hello

I look for informations about paleographic dating of Qumran manuscript (sign. 4Q204).

Can You propose me any science publications or scientists, who can give me informations?

Cyprian, Poland