Wooden Ship-Cart Model, late 13th–early 12th century B.C. Wood with traces of paint, 5 3/16 × 15 3/16 × 2 3/16 in. Courtesy of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo: J. Paul Getty Museum, Rebecca Vera-Martinez

Ancient Egypt conjures visions of towering monuments and glittering gold, but it’s often the small, unassuming archaeological finds that yield the deepest insights. The exhibition Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World explores some of these underappreciated objects and what they can tell us about the complex interactions among ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. This small wooden ship-cart model from an Egyptian tomb is one example.

In 1920 the great Egyptologist W.M. Flinders Petrie excavated at Gurob, a site located at the entrance to Egypt’s Fayum district. One tomb contained a wooden ship model, together with pieces that had come off it. The model replicates a Late Bronze Age Mycenaean Greek warship, probably a pentakonter (fifty-oared ship). The “Sea Peoples”—a term used to describe the coalitions of migrating peoples who factored into the end of the Bronze Age, around 1200 B.C.—adopted and adapted this ship type, as we can see from the dramatic naval battle portrayed on the outer wall of Ramses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

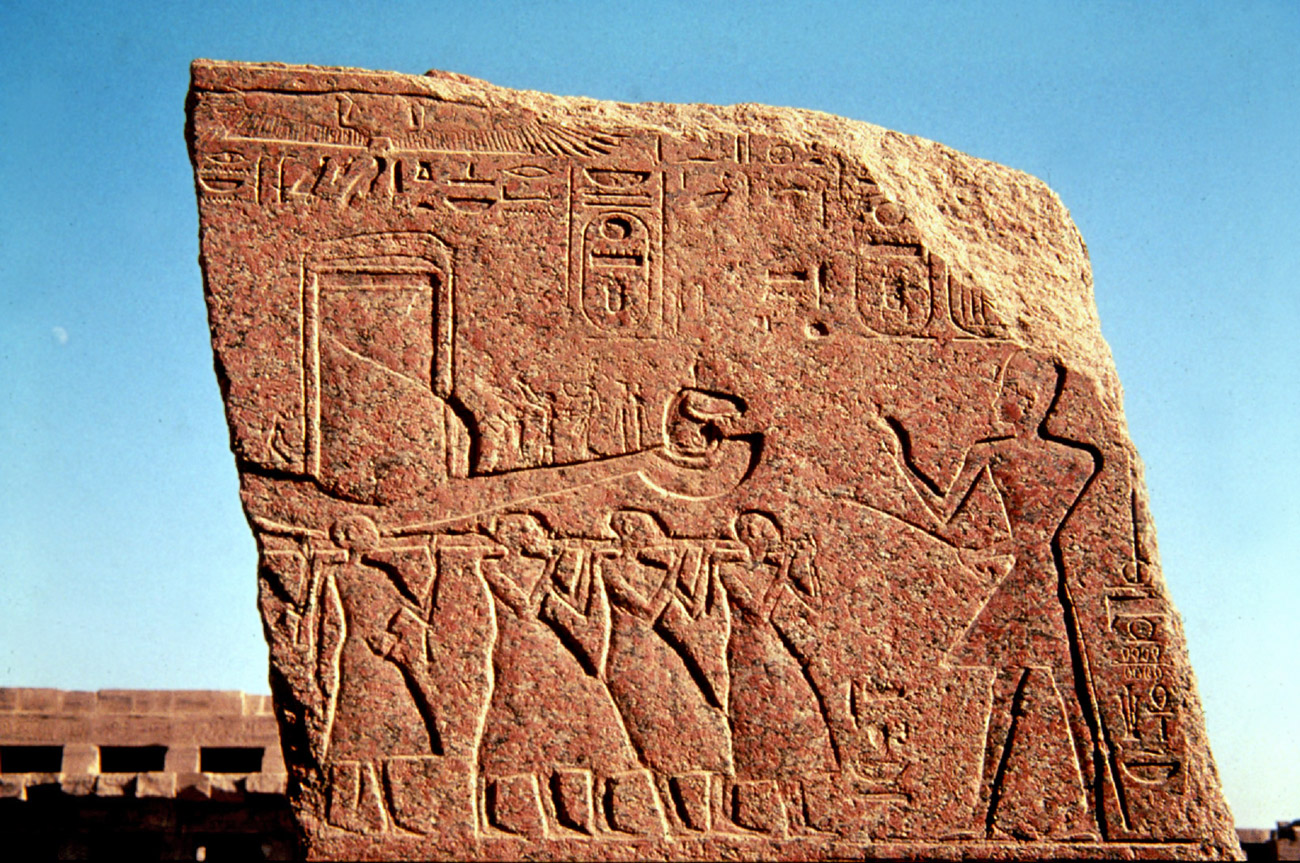

One of the five Sea Peoples’ ship depictions in Ramses III’s naval battle scene. Medinet Habu. From Wachsmann 2013: 38, fig. 2.5

Reaching the Near East during the Sea Peoples’ migrations, this vessel served as the prototype for later galleys (oared ships) built and used by both the Greeks and the Phoenicians. When Greek triremes defeated Phoenician triremes at Salamis in 480 B.C., both vessel types descended from the same original Mycenaean pentakonter, making it arguably one of the most significant ship designs in history.

Unfortunately, no shipwrecked hulls of such a Bronze Age galley have come to light, so the Gurob model remains our single most important piece of evidence for understanding these remarkable vessels. Put simply, if Helen of Troy’s face launched a thousand ships, then at present the Gurob model is the nearest we can approach that ship type.

The model, together with some of its detached pieces, were all that Petrie’s assistants found in the tomb. Prior to its interment, someone had disassembled the model and broken the hull in two, apparently intentionally. A number of the model’s parts are missing. The model retains its forecastle, however, although the fence is missing. The stem ends in a typical Mycenaean bird-head device, with a strange vertical beak known from other ship depictions. A structure now indicated solely by patterns of missing gesso, would have existed in the stern also.

Significantly, the model documents well the supporting stanchions postulated previously solely on the basis of two-dimensional representations of this ship type: the model has both miniature stanchions and rows of holes piercing the upper edges of the model’s caprail (upper edges of a ship’s hull), indicating their placement.

Four painted wheels, together with additional evidence, indicate that the model originally could have been displayed with a wagon-like support structure. At first glance, one may be excused for assuming that the model served as a child’s toy. One would be wrong, however.

The four wheels. Courtesy Petrie Egyptological Museum. Photo: S. Wachsmann

A diminutive decorated rectangular slip of wood, pierced at its center, was meant to sit beneath the hull. In this manner, the piece could be attached by means of a peg to a hole cut into the underside of the hull amidships. But what does this piece represent?

The pavois. Courtesy Petrie Egyptological Museum. Photo: S. Wachsmann

In ancient Egypt, people depended on the Nile as a main transportation superhighway. It is hardly surprising, then, that watercraft played an integral role in Egyptian religious life. Egyptians had the periodic need to transport ships overland, for three primary reasons: for funerary rituals, to move gods in ship-shaped palanquins, and for divination. The normal manner of carrying these cult “ships” overland was on the shoulders of porters, by means of long poles. The carrying poles required a base for attachment, as well as for the support of the ship itself: the Egyptologist George Legrain termed this base a pavois (French for “shield” or “buckler”).

Ancient land-based Egyptian cult ships were normally, although not always, carried on long poles supported by priestly porters. Thutmose III. Photo: S. Wachsmann

The appearance of this modest slip of wood, representing a pavois, on the Gurob model is highly significant. It indicates that the model is no simple child’s toy (my original assumption), but rather a cult vessel. It also points to a syncretism in which a European cult that used such “ship carts”—likely the cult of Dionysos—is seen in the process of assimilation as it adopts Egyptian cultic affectations. The cultic nature of the model also explains why the model and its parts were found alone in the tomb: the model may have been buried by itself due to its cultic significance.

The wheeled-cart aspect of the model is decidedly un-Mycenaean. The model’s wagon belongs to a cultural phenomenon of cultic objects that appear in the twelfth century B.C. in the Aegean world, apparently arriving from farther north in central Europe. In fact, the Gurob model should not be understood as replicating an actual ship. Rather, it represents a land-based cultic ship (cart) that had been patterned after an actual ship, in this case a pentakonter. Put simply, the Gurob model is a copy of a copy. And while the Gurob model was thus twice removed from the original war galley that served as its prototype, the information that the model supplies regarding the transfer of cult in the seam between the Late Bronze and Iron Ages cannot be overemphasized.

The Gurob model also bears painted decoration, which imbues it with additional value, contributing to our understanding of the color epithets employed by Homer when describing the ships of his heroes. We literally see what Homer meant by his “black” ships: he refers to the pitch on the ship’s hull as seen on the model.

The Dakhla Oases ship graffito. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society. Photo: H. A. Winkler

The Gurob model must be considered in relation to the only other iconographic sources for Aegean galleys known from Egypt: the naval battle depicted on Ramses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, and a remarkable graffito from Dakhla Oasis, which depict these vessels employed in warfare and cult.

The Wilbour Papyrus, a cadastral document concerned with documenting the ownership of land for taxation purposes, together with additional textual evidence, indicates that one group of Sea Peoples, the Sherden, lived in and around Gurob contemporaneous to the model, raising the likelihood that the model belonged to someone of Sherden descent.

In researching the Gurob model for my book The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context, I enlisted the help of Dr. Donald Sanders, president of the Institute for the Visualization of History. Donald and his colleagues built a free-access companion website for my book on the Gurob model that includes fully rotatable 3D virtual models of the Gurob model as found, together with two possible reconstructions: one with the model mounted on wheels and the other as it might be constructed to be carried by porters. Building the virtual model proved to be remarkably valuable in the research stage. We learned, by error, for example, that the wheels had been made as two pairs. When the pairs were mismatched, the model stood unevenly. The website also contains maps, satellite photos, and a complete collection of high-resolution color images of the model and its parts, which appear in black and white in the book.

Building a virtual 3D model of the Gurob model revealed many secrets. Manipulate the 3D virtual model here, and see more virtual models of the Gurob ship-cart here.

We learned, for example, that the wheels had been prepared in “sets.” This became clear when we originally mismatched the wheels. Courtesy of the Institute for the Visualization of History. Images: D. Sanders

Unless and until someone discovers, excavates, and reports on a Mycenaean or Sea Peoples galley, the Gurob ship-cart model may be the closest we will ever come to this truly remarkable ship type, which played such a significant role in the changing the course of world history at a critical juncture.

Text of this post © Shelley Wachsmann. All rights reserved.

The ship model might just be my favorite object in the Egypt exhibition, so I really enjoyed this blog post, as well as your entry in the exhibition catalogue. It’s especially fascinating to me since I work on Athenian religion, and naturally I thought of the Panathenaic ritual ship. So naturally, I’m interested in its cultic associations, and specifically, its deposition in the Gurob tomb. You say that the model was taken apart and its hull broken in two, “apparently intentionally.” Do you think this was part of its ritual use, as was its burial?

Thank you for this post, as well as the links the fabulous 3D virtual models!

Hi Jacquelyn,

Thanks for your comment. My book on the Gurob model includes a chapter entitled, Wheels, Wagons and the Transport of Ships Overland. This turned out to be one of the most interesting—and downright fun—topics that I have had the good fortune to research. I deal with the Pananthenaic ship in some detail on pp. 132-155.

And yes, I think that the model’s hull had been intentionally broken for ritual purposes. On the possible explanations for the ritual ‘killing’ of burial items, see Grinsell’s article:

Grinsell, L. V., 1961. The Breaking of Objects as a Funerary Rite. Folklore 72: 475-491.

Shelley

Thank you for this in-depth look at the ship-cart model, which we’re very fortunate to have on loan for “Beyond the Nile.” I’d like to give a shout-out to the Getty’s mount makers, who constructed a new, custom mount for the fragile model so that it can be safely displayed (see the first photo above). The object is broken into many small fragments that up until now had been kept in storage at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London. Now, when the object returns to the Petrie Museum on its new mount, it can go on display and be enjoyed by visitors!

Hi Sara,

Thank you for inviting me to write this (my first!) blog post. Much appreciated.

I also want to commend the Getty for the beautiful display that your Mountmaker, Richard Hards, created for the model and for also attaching the vertical bird beak to the stem and mounting it so that it faces outboard. Big improvements!

I take great pleasure in seeing that the Gurob model is now receiving the attention it so richly deserves after its many years of obscurity. Kudos to the Getty.

Shelley

Fantastic blog post about this intriguing model, which I had seen in the ‘Beyond the Nile’ exhibition. The accompanying website with the reconstructions is absolutely fascinating and really helps in understanding how it might have once looked and its ultimate function as a cult item. I’m also fascinated with the apparently ritualistic breaking of the ship – something I know was done to many types of cult items, usually statues.

I’m curious, however, that the ‘awning’ pieces weren’t used in the reconstruction. The original Petrie Museum photos shows their interpretation of how those pieces might have been used, but it seems there’s too much doubt now to be sure? I would expect some sort of awning over those pegs, or an enclosed shrine area, much as seen in Khufu’s solar ship. So curious about this.

Thanks for the kind words Stephen.

I do not accept Petrie’s reconstruction of the awnings. In truth, these pieces remain a mystery to me. In my Gurob book I discuss my various attempts to make sense of them in the context of the model (pp. 23, 25 fig. 1.25)—including as ‘fenders’ on a reconstruction of the now-missing wagon, but came up with no solution that satisfied me. All I can conclude is that they presumably served some purpose on the model or its wagon.

Shelley

Dear Shelley,

Thanks for a great post. How wonderful to see the way that the Getty has followed your reconstruction in putting the Gurob boat back together and how splendid it looks on the Getty mount! i only wish I could get to the exhibition.

It has given everyone at the Petrie Museum great pleasure to see it treated with the respect it deserves and, as deputy director of the current Gurob excavations, it fills me with delight. One by one the Gurob objects come back to life…

Thanks again, and love the book!

Jan Picton

Hi Jan,

I will be forever grateful to the folks at the Petrie Museum for allowing me to research the model. It is certainly one of the most fascinating and thought-provoking artifacts I have ever dealt with.

All good wishes to you, Ian and the team with your continuing work at Gurob.

Shelley

I was blown away by this exhibition. Moreover, just thinking about the mechanisms and care for transporting these priceless relics. Thank you museums, curators, and caretakers of such important artifacts and relics.