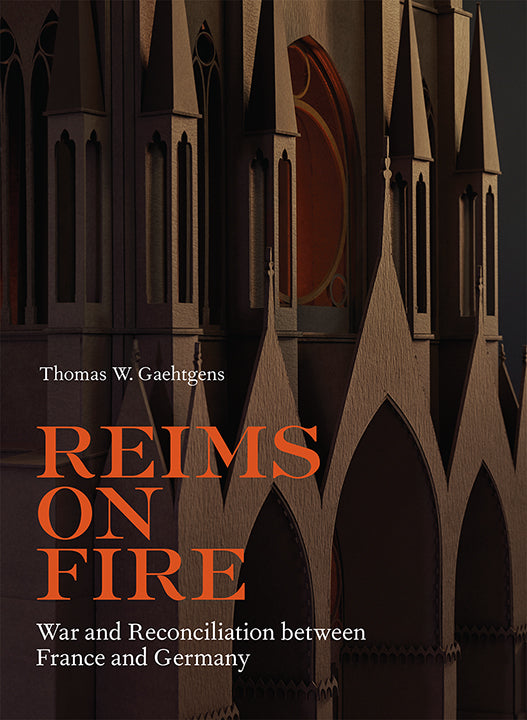

How do we understand the seemingly senseless destruction of monuments during World War I? How does art history dovetail with military history? In this episode, Thomas Gaehtgens explores these questions through the lens of Reims Cathedral. He traces the history and symbolism of this iconic gothic building through the war and after, investigating the roles of culture, scholarship, and media in shaping our understanding of World War I and its legacy. Gaehtgens is director emeritus of the Getty Research Institute, and his new book from Getty Publications is titled Reims on Fire: War and Reconciliation between France and Germany.

More to Explore

Reims on Fire: War and Reconciliation between France and Germany publication

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

THOMAS GAEHTGENS: What the reasons are, nobody cares then. You know, the fact that Reims Cathedral has been attacked was enough to appall everybody.

CUNO: In this episode I speak with Thomas Gaehtgens about his new book, Reims on Fire: War and Reconciliation between France and Germany.

Reims Cathedral is a monument to French national history and identity. Built in the High Gothic style, the cathedral served as the site for royal coronations. When it was bombed by German forces during the First World War, it took on new meaning as a symbol of the rupture between France and Germany.

The complex political and ideological history of the cathedral is the subject of Thomas Gaehtgens’s recent book, Reims on Fire: War and Reconciliation between France and Germany. Thomas is director emeritus of the Getty Research Institute. I recently sat down with him to discuss the book and the various meanings Reims Cathedral took on in the years following World War I.

CUNO: So what were the political and military circumstances that led to the shelling of Reims Cathedral by German artillery forces in September of 1914? And what was the purpose that the shelling served the German army?

THOMAS GAEHTGENS: Well, there was no purpose.

CUNO: There was no purpose.

GAEHTGENS: There was no purpose. Well, one has to look into the story in the context. So right now, there are many, many commemoration events concerning World War I, between 2014 and 2018. And in this context, many exhibitions, many books have been written, and many publications, and the whole story of World War I has been, in a certain way, reviewed. And in this context, the shelling of the Cathedral of Reims has been neglected. So I thought it was very important to bring this story out.

So what happened was the following. The German army invaded innocent Belgium, neutral Belgium. And their goal was to get, as fast as possible, to Paris, with all their strength they had as an army. And they found first a lot of—not really important—but they found, you know, strong Belgium irritation. So the Belgians tried to stop this big army. They couldn’t, but they were really fighting courageously against this big army.

And the first very important event happened in Leuven. And in Leuven, a very unclear situation, which is still very, very controversial, was that not only many people died and it was a very foggy situation, as one says. It was not quite clear what happened. But in any case, the library of Leuven burned down. [Cuno: Right] And all the manuscripts, very valuable manuscripts since the Middle Ages, and especially a very important collection of Medieval manuscripts, were lost.

And there was an outcry internationally, that the Vandals, the German army, the Vandals had entered the country and that the Germans were not only fighting a war, a military process, but were trying to, in a certain way, destroy the culture of the neighbor. This—

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] So the— so the assumption was that that was a determined position for the Germans to take [Gaehtgens: Right. So—] on the purpose; they shelled it for that reason.

GAEHTGENS: Absolutely. So the idea was the Germans invaded the country not only to be victorious, but also to destroy the monuments. The word, the key word, is Vandal—Vandalism. We’ll encounter that more often. So after Leuven, the German army continued to move forward, already with the reputation, this army is devastating. And they are not only looking for military victory, they are looking for destroying French culture. So that is the situation.

Now, when we come now to Reims, it becomes also a little bit foggy because the situation is not completely clear. But I had a lot of work to do to pull the different sources together and try to clarify the situation. In fact, there were two German armies, the Saxon and the Prussian army, at the same time moving towards Reims. And they were not communicating in a good way.

And the Saxons arrived first, and they sent delegates into the city. And these delegates were talking to the mayor and announcing that they wanted to enter the city. The city had no military at this moment. And—

CUNO: No French military.

GAEHTGENS: French military. And they were talking to the mayor and at this very moment, bombs fell. So the Germans in the city of Reims were completely irritated because they didn’t understand. Who was shooting? Who was shelling? And they thought the French were advancing. But in fact, the Prussian army arrived. And the Prussian army also had sent delegates into the city, and these delegates were taken by the French army.

So the Prussian army thought, well, they took our delegates; let them get some bombs to know what it’s all about. And so then the Saxons who were in the city, of course, discovered then that the Prussian army arrived, and they stopped then. And then the Prussian army moved into the city.

So the first shelling of the city was, in a certain way, to answer to the fact that the delegates have been taken. And there was not a lot of damage, but one shell also hit the church. But it was only a minor damage. So that was the first situation.

CUNO: Is Reims in any way strategic? Or was it just simply on the way to Paris, and so they just—

GAEHTGENS: It was on the way to Paris.

CUNO: It had no strategic role to play in the battle?

GAEHTGENS: It was strategically interesting because, you know, there was another war in 1870, ’71, when the Prussian-German army invaded France and really got to Paris. And that was even the model for the second campaign in 1914. However, after the defeat in 1871, the French built Reims as a fortress, so it was interesting to take it.

But this incident in Reims in September ’14 was— They just passed there, they wanted to take it and then move forward as fast as possible to Paris.

CUNO: You say in the book that this art historian, Count Georg Vitzthum, took a tour of the cathedral shortly after the attack. And you say that this proves that the idea the German officers intended to destroy the cathedral is, in your words, utterly baseless.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah. Well, again, the context. So what happened after was very, very interesting. The Germans then moved into Reims. And they stayed there only a little bit more than a week, but they were installed in Reims. And then a very important battle started. This was the Battle of the Marne, which was a turning point in the campaign to France, for the German army.

And the Battle of the Marne was a battle where, for the first time, the German army was stopped. And my idea is the war should have been over at this point because, you know, the Germans didn’t get their goal. They couldn’t reach Paris. They stopped, and the French, helped by the British, moved forward. And then from this moment on, the fight in the trenches started.

So the first weeks of World War I on the west side was a campaign moving forward very fast, when the German army was stopped, went into the trenches, and neither the French nor the Germans were moving anymore. They were sitting, lying, dying in the trenches for four years. This was a terrible situation. And the Germans stayed just in front of Reims. And of course, they were shelling, bombing, over four years, and the city of Reims was a devastated city at the end of the war.

One really interesting and important moment is that, you know, you should know that after military law, if a city is empty of military, you are not supposed to shell it.

CUNO: Yeah.

GAEHTGENS: But since the French moved into the city, the Germans were, of course, bombing. And the reason why it started then was— The Germans never intended to attack the church. But at one very moment—and it’s also very controversial, but I think most of the people agree now, because there are also French sources telling this story—the French brought some observers on top of the north tower, to observe the movements of the German army.

And then one officer gave the allowance to shoot, to try to get this observer off. And that, of course, was not a good idea. And the cathedral started to burn because there was a wooden scaffolding and this got into fire, and the fire went into the roof, and then the church really got destroyed heavily.

CUNO: Your book is so much about the role of art historical and cultural debate, with regard to monuments of artistic significance and national significance, what is it about this German art historian, Georg Vitzthum? Was he important? And why was he there?

GAEHTGENS: Well, you know, I’m really not a military historian. I got really involved in this military history, but I wanted to clarify the situation. If not, you cannot really describe the whole story. Vitzthum was a very professor of art history in Kiel. And he happened to be in the Prussian army, as an officer on the west front. He just was there.

So he moved with the army, into Reims. I looked into all the details and all the archives. I mean, there is a little, little doubt, but I’m quite sure that he was the officer who guided his colleagues into the cathedral, to tell them about the history of the Gothic architecture and tell them how important and wonderful this monument is.

This source, that there was a German officer giving a guiding tour for his colleagues, is reported not only from the German side; also from the French side. So that is absolutely sure, that that happened.

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] Did he do this just because he was interested in the cathedral and he wanted to share his enthusiasm with his colleagues? Or was it to help them understand that this should be protected, this shouldn’t be shot?

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] I think— I— That’s a very good point. I think both. I think he— Of course, his enthusiasm. He was a scholar of Medieval manuscripts and architecture, so he knew, of course, about the importance of the Gothic cathedral. And they had nothing to do. I mean, they were sitting there, were bivouacking in front of the Church. So he was, of course, then trying to show them the beauty of this architecture.

CUNO: Yeah. Let’s step back from the war some many centuries, to the building of the Reims Cathedral. Tell us about the importance of the Reims Cathedral within the history of Medieval architecture.

GAEHTGENS: Well, shelling a cathedral should never be done; but shelling this cathedral, the Germans should really have been very, very careful in doing this, because this is probably one of the most symbolic cathedrals in France, because the French kings have been coronated, since the Middle Ages, in this church, until the early nineteenth century.

And so you know, the coronation is a very important symbolic moment in the understanding of what the French state represents. It is the moment when not only the king is crowned, but it is the moment when he gets the holy oil. He is, in a certain way, fulfilling a contract with God. So he has a half priesterly importance.

He is of course, the king of the state, but he is also the person who represents and vows to defend Christendom. At this very moment when he is crowned, this obligation, this commitment to the state and to the Catholic Church happens.

So this place is not an ordinary cathedral and an ordinary church. There are other churches, like Chartres or Amiens or others, Notre-Dame de Paris. This is a monument which has a high symbolic charisma for the French state. And so if you, in a certain way, try to attack this national monument, you attack the heart of every French. And that, of course, explains the outcry, not only of the French, but of the international press and authors, writers, scientists.

Everybody was appalled to do this. It’s a little bit like, you know, you wouldn’t attack the Vatican, you know. That’s absolutely impossible. So Reims is the French Vatican, in a certain way. So— and you cannot— you cannot attack this church.

CUNO: You say in the book that it was one of the most significant media events of the First World War.

GAEHTGENS: Yes.

CUNO: Tell us about that. Give us a sense of the character of the response of the international press to the bombing of it. You call it “curious, absurd, sometimes even ridiculous and repugnant.”

GAEHTGENS: The basis of the outcry was hatred. It was not only reported in a neutral way; it was talked about in a way of, you know, the Germans did something completely inhuman. And that’s where the word vandalism comes in.

So it was not a normal war report; it was a kind of reaction, and also an emotional reaction, to this absolutely impossible event. What the reasons are, nobody cares then. You know, the fact that Reims Cathedral has been attacked at some point was enough to appall everybody. And you know, first of all, we have to understand that at this very moment, the diffusion of such an event by photographs went very fast.

So photographs were distributed all over the world very fast. And the knowledge of this event, came, via telegraphs and other ways, to America, even to Southern America, to Asia, all over. And it was in every newspaper. And in all languages. And the tenor of the reports was the German vandalists destroyed French culture. It was not a military victory, it was the destruction of French culture.

CUNO: Of course, that was the response of the press on the west side—the French, the English, whatever.

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] On the west side. Yeah, the west side.

CUNO: But what was the German response?

GAEHTGENS: Well, me just add one phrase to the— So photographs were one thing; then the press were the other. And these two ways of diffusion were like the Titanic. You know, after the Titanic, this was the second huge event in early twentieth century, when everybody was involved. So the German side was unprepared. You know, they didn’t think of this. They couldn’t even prepare that they were attacked in such a terrible way.

So the Germans couldn’t understand that they were attacked as vandals. They could understand if they were attacked about their military victory. But why would they be treated as Huns, barbarians, and vandals? And they were not prepared to that. And the reaction was— Well, first of all, there was censorship. But then also, they pulled together and there was a manifest, a memorandum, of the ninety-three people, which was published.

And the most important people signed this protest. This protest was directed against the fact to be labeled vandals.

CUNO: Yeah. We should— let’s back up on that. Because you that say the First World War was interpreted as a cultural contest between France and Germany.

GAEHTGENS: Yes. Yes.

CUNO: Between German barbarism, as it was characterized, and cultured French civilization, as it was characterized. And you quote from many, many writers, including the philosopher Henri Bergson and the novelist Romain Rolland, on the French side; and then you quote from the manifesto of the ninety-three on the German side Characterize this debate as a cultural debate, between the concepts of civilisation and Kultur, and the role that intellectuals played in formulating that debate.

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] Well, first of all, one has to see that after the shelling of Reims, there was no conversation between French and Germans anymore. You know, we have close relationships over hundreds and hundreds of years between these two countries, you know? Scholars, scientists, they talked to each other. Whatever the politicians do, they talk to each other. But at this moment, there was no conversation possible anymore.

And you know, it is very interesting how it all started. Henri Bergson, the famous French philosopher, he started already with a lecture he has given before the start of First World War. Before the Germans invaded Belgium, he gave a talk. A couple of days before, he gave a talk and said, “It is coming. The war will come, and it will be a fight between civilization and barbarism. It will be a fight between civilization and Kultur,” in German—and culture.

So there is a difference between these two concepts of civilization and culture, written in German, “Kultur.” And you know, many caricatures and man writings relate to this kind of distinction. It’s not easy to define that. It goes back a long way, into at least the eighteenth century, probably even earlier. And there is a distinction.

You know, civilization, in the French sense, is— are the goals and the principles defined by the French Revolution. It’s liberty, fraternity, equality. And the idea that politicians should make progress in a civil society, to propagate these ideas, not only in France, but all over the world. I mean, in America, of course. The idea of the French Revolution was realized, in a certain sense, in America, for good or for worse.

And the German idea of Kultur is different. It is based on the idea of the people and the blood and the race. So kultur means having an identity of the common language and the common background and where you come from. So these two concepts still exist today. So I understood that as a French, for example, you can more easily have an American or a British passport at the same time. So you can have two passports. You have only to conform with the ideas of a civil society, on the basis of the French principles.

For Germany, it is difficult. I cannot get an American and a German passport. If I want to have an American passport, I have to give my German passport, because I belong to—by language, by background—to the Germans. And so I mean, I can change my identity, but then I have to give up the other one. So that’s a very interesting [inaudible].

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] So this debate or this difference dates back to Fichte, to Kant—

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] Yes, absolutely, to the eighteenth century, yeah.

CUNO: And into the French Revolution.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah, right. Yeah , right.

CUNO: And then it carries itself out, so there’s a long legacy, by the time we— [Gaehtgens: Yeah, right] the time we get to 1914.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah.

CUNO: You describe a war of images exchanged by French and German artists, and an exhibition in Paris, at the Georges Petit Galerie, of pastels by Adrien Sénéchal, which were inspired by Monet’s paintings of the Rouen Cathedral. So all of a sudden these paintings, these pastels, were exhibited for the reasons of propagating this vision of cultured France and civilized France? Give us a sense of this war of images.

GAEHTGENS: Few of the paintings. I mean, you know, we are in the midst of a war, still painters continued to paint; but what I mean is that there are, in a certain way, three layers of visual material. First of all, photographies. Photographies were distributed very fast, also by postcards. And the photographs were also manipulated.

So for example, you can see many, many postcards with flames coming out of the roofs. There were no flames; there was only smoke. There were postcards of devastated statues. You know, they were all cut their heads off. These were manipulated. The sculptures were very much destroyed, but it was— So there was a propaganda campaign.

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] It was a kind of iconoclasm.

GAEHTGENS: Absolute. There was an iconoclasm in images. Well, the second part were, of course, postcards and caricatures. And many, many of them. So many were distributed all over France and England and America. They were sent all over. And this was another way to tell the story of what happened in Reims.

And then the third one were these paintings you are taking about. The exhibition was with paintings by a painter called Sénéchal, who was in Reims when Reims was shelled. So he experienced the shelling. But you know, the paintings were made later. I mean, the bombs were falling. You were not, as a painter, there painting when the bombs were falling. So he reconstructed, in several hours of the shelling.

However, these paintings also were exaggerating. You know, it was full of flames, which he never had seen. And he couldn’t even go that far and, you know—But there is, in a certain way, some kind of personal experience in these paintings. And then there are more paintings by other artists later, after the war, showing the ruin, the ruin as a new symbol.

CUNO: These are French painters or German?

GAEHTGENS: French painters. French painters who painted Reims as a ruined city. Not only [the] cathedral was in ruins, but the whole city was in ruins. I mean, you know, there were, I think, 20,000 people still in Reims, and it was several hundreds of thousands before. The city was a ghost city. It was a ghost city and was completely destroyed. And this is very moving. And we have many photographs, also, of the completely destroyed city of Reims.

CUNO: Yeah. So the war is on and the armies are fighting each other. You’ve got intellectuals arguing with each other about this; you’ve got artists painting and— pictures that play into this debate. But an extremely interesting part of the book is the role that art history plays in this. So we’ve already mentioned that Reims was an extremely important Gothic cathedral. But you talk about the myth of the Gothic in France. And I’m especially interested in the role played by art history and the art historian Émile Mâle.

GAEHTGENS: Yes.

CUNO: What position does he take? How does he articulate the position? And who reads his writings, or who hears his lectures, and how does that factor into this big fight?

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] Well, I’ll give you a little background. I mean, you have to know that the history of the scholarly discovery of the importance of Gothic architecture and Gothic art in general starts, let’s say, in the late eighteenth century and in the nineteenth century. The Middle Ages were dark ages, until the eighteenth century. But a very fascinating process started around 1800, where both countries, the Germans and the French, claimed that the Gothic is theirs.

And this is a conflict which went until the shelling of Reims. So you have a hundred years of controversial conversation about the role of the Gothic. And this started— I mean, let’s start with the French. The French started to rediscover the Middle Ages, you know, with Chateaubriand and Catholicism and with the style troubadour, Romanticism, Victor Hugo, the novel Notre-Dame de Paris, which interprets the Gothic as the style of the people.

Victor Hugo’s idea is these cathedrals are not built by a few people and by the noble people—the Gothic is a style of the people. Every Paris man and woman took part in this process. And then comes a very famous architect and art historian, Viollet-le-Duc, who did thorough art historical and architectural examinations and investigations, and restored the Gothic cathedrals and Gothic churches, and renovated them—not always in the right way.

And then in 1898, two very important books were published. The first was by a novelist, Huysmans. And he wrote a book. The title is La Cathédrale. And he was describing the Gothic cathedral as a monument in which you get elevated. You cannot have that in a Roman architecture or in a temple, in a Greek temple. But Gothic architecture elevates you because of its form.

CUNO: And the colored glass.

GAEHTGENS: The colored glass. All this. And you get not only elevated, but you get convinced that in a certain way, you must become a religious person. A Catholic religious person, if possible. So this was a new understanding, interpretation of Gothic architecture. And at the same time, 1898, another book was published by an historian, an art historian, Émile Mâle. And he was, as historian, as a scholar, describing Gothic architecture, in a way, to decode the meaning of the architecture and the meaning of the statues and the histories which were told in the glass windows.

So in a certain way, he was reconstructing the narrative of the architecture and the decoration of the architecture, to understand that there was a religious background and a story told to the visitor and to the believer going to the church. So this happened at the same moment.

Now, Émile Mâle was becoming one of the most important art historians of his time, very famous. This was a very popular book. Proust was reading this book and admired this book. And then when the Germans shelled Reims—I mean, I have to repeat it; they shelled Reims. And the cathedral was also hit, but it was not only the goal to destroy the cathedral. He was, of course, devastated that this church was destroyed or heavily hit by bombs. He couldn’t understand that.

And then he wrote a very nasty book against the Germans, saying the Germans were only copying French art; they have never invented anything; they are not even able to do art. And they are, of course, Vandals, barbars, and so they want to destroy French art and French culture, from the very beginning. Now let’s go to the German side.

CUNO: Yeah, the German art historical response was equally interesting.

GAEHTGENS: It was intriguing. I’ll come to that. Because now, German interpretation of Gothic is different. But it relates to the idea of Kultur, of culture, because it all starts with Goethe. And Goethe visited the Minster of Strasbourg, where we have the name of the architect, Erwin von Steinbach. And he, at the end of the eighteenth century, he admired and experienced Gothic architecture. And he says, “This is German Gothic. And the French cannot have built this, because the French are about Greek and Roman architecture.

“They are about harmony. They are about, you know, the proportions of these things. But this architecture comes out of the idea of the wood and—”

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] The for— the forest.

GAEHTGENS: The forest.

CUNO: The great forest of Germany.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah, the forest in Germany. And you have another feeling. You have— You go into this wood and you experience— You know, it goes high up into the heaven. And this is not French at all. French is proportion, you know, and Greek-Roman architecture. That’s southern Roman tradition. And this is German.

And this experience goes on. And the idea of Goethe was transferred into Romanticism. And now in early nineteenth century, during the Romantic period, there was one building which became then a symbolic importance—in a certain sense, like Reims. Like Reims. And that was Cologne. And Cologne Gothic architecture was unfinished.

The Cologne Cathedral was unfinished. There was the choir and there was the western part, with unfinished two towers. And in the middle, there was only, you know, the basis. And now the Germans, identifying with Gothic architecture, decided to continue and to finish Cologne Cathedral as a cathedral where all the German states are working together to finish this cathedral.

So Cologne became the national cathedral for all the Germans. And the Prussian king supported it, paid for it, and all the different states in Germany contributed also. And then in the later nineteenth century, it was, of course, clear and the scholars, of course, knew that the Gothic started in the Île-de-France. There was no doubt about it. But the scholars had problems to accept that because it was so deeply rooted in their intellectual background.

And we have, still around 1900, German scholars saying, “Well, you know, the better Gothic architecture is in Germany. And the Gothic buildings in France are prefigurations of the later Gothic architecture, which can be found in Germany,” in Bamberg, in Cologne, and wherever. And one author, Wilhelm Worringer, [Cuno: Yeah] was one of them, who in a certain way, stated that the real, you know, high point and peak of the Gothic architecture development was in Germany.

And of course, publishing this kind of book, the French must have been appalled to read that. And this, of course, brought the two sides, the Germans and the French scholarship, against each other. And of course, the German art historians were very nationalistic, as were the French. So there was no way to come to common ground. Only very few people could make, really, a distinction, could distance themself from these kind of engagements, during this First World War.

CUNO: Now, you write about something called the Kunstschutz.

GAEHTGENS: Yes.

CUNO: What’s a good translation of Kunstschutz?

GAEHTGENS: Protection of art. And protection of art and protection of architecture.

CUNO: What role did that play in this story?

GAEHTGENS: Well, the Germans had no real response to the huge critique which came, not only from France, but from all the countries around the world. But they had one very good response. And that was, they invented the protection of monuments, the Kunstschutz as a kind of department attached to the military. And this was decided as a consequence of the heavy criticisms against the vandals, to demonstrate that the Germans were no vandals.

And they had in the military, since 1915, a group of art historians to consult the army and the officers, to avoid moving forward or to shell with their cannons, this monument or this city. Whether that was very effective is another question. It was effect in a certain sense, in certain locations; but it was not effective overall. But these people and the head of these group of art historians was Paul Clemen, who was the director of the conservation of monuments of the Rhineland.

He was moving right away, in 1915, to Belgium, inspecting all the different places where destruction were, and he was even trying to get roofs over the buildings, and they were trying to pull together paintings out of the museums to protect them and so on and so on. So it was a very important propaganda move or counterpropaganda move. And that was definitely the first idea. But it was also effective, and a model for later periods, because in the Second World War, it was officially attached to the German army.

And in the Second World War, it was extremely effective. And the officers, who had no real power, but who were playing a very, very good role in trying to prevent that the army really moved forward without knowing that there were cultural monuments to protect.

CUNO: Yeah. So our listeners will probably recognize the term Monuments Men.

GAEHTGENS: Monuments Men, yes.

CUNO: Same kind of idea.

GAEHTGENS: Absolutely.

CUNO: But a earlier war, perpetuated until the Second World War.

GAEHTGENS: Absolutely. But the Monuments Men, in a certain way, were modeled after the Kunstschutz. However, the Monuments Men came after the fact.

CUNO: After the destruction had occurred or after the…?

GAEHTGENS: They also had uniforms, they were moving forward, but they were behind. And—

CUNO: Behind the armies.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah, behind the armies. But in fact, this is more or less the same thing.

CUNO: Yeah. [Gaehtgens: Yeah] Now, after the war, both sides, you write, compiled an account of the destruction and the protection of cultural monuments during the war. And Paul Clemen, the man you mentioned earlier, was involved in this. So the war is over. After the war, they come in and they take an assessment of what [Gaehtgens: Yeah] needs to be done to restore these monuments and—

GAEHTGENS: This is a very fascinating period, also, because one has to consider that the French were victors. They were victorious, but their country was destroyed. And the country of the losers, the defeated, was not hit.

CUNO: Because the battles occurred in France, not in Germany as much.

GAEHTGENS: In Germany, nothing happened.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah.

GAEHTGENS: So Northern France was really devastated. The French first had to make a kind of inventory, what to do. And of course, this was a huge task. And they started with trying to help first to get the people back. And then of course— France was, at this moment, really not very rich, so they had no money really to start with rebuilding the monuments. And the American help, especially by Rockefeller, was extremely important to support the reconstruction of Reims Cathedral.

Not only Reims Cathedral, also other places. But what is interesting at this moment, that many considered that the ruin of Reims should stay. And for the future, this should be a monument of what the Germans did, and that the Germans are vandals, and forever, the best monument would be to keep the ruin of Reims.

Since Viollet-le-Duc, since the nineteenth century, there was already a conversation about, can we reconstruct Medieval buildings? So Rodin, for example was arguing that a statue of the Middle Ages cannot be restored. Don’t touch it. Let it in the state it is.

And proposals were made to have the flags of all the countries who fought against Germany. And that like a monument of the anonymous soldier, they would be honored there and then forever the story and the history of the event of the shelling of Reims could be commemorated.

But at the end, I think that— it is perhaps my view, but I think that the French understood that this would be also a monument which commemorates forever that they were defeated by the Germans. And the church, which wanted to rebuild the church, they won over and they reconstructed Reims Cathedral, and the whole city, of course. With—I have to stress that again—with the help of the Americans. Also other countries participated by donations—the Swedish, the Danish; all European countries were participating and helping to reconstruct Reims.

CUNO: So it reopens in 1938. And then there’s a big day in 1962, after the Second World War. So I want you describe ’38 and then ’62, but then also to reflect upon the role that Reims Cathedral has played in this kind of a point of healing between [Gaehtgens: Yeah] the warring countries.

GAEHTGENS: Well, that is a very interesting question and important point. First one has to recollect that in ’38, the church was reopened; and in ’39, the Germans were again there. But this time, the Germans avoided to do anything and they were not shelling the cathedral, they were not shelling Reims. So they were careful to learn from the events of the First World War.

But then after ’45, it took a long time. It took years and years to, in a certain way, rebuild some kind of relationship with France. And it was de Gaulle, Charles de Gaulle, who took the initiative. And he had found his partner in Konrad Adenauer to, in a certain way, build a new bridge between these two countries.

CUNO: These two heads of state.

GAEHTGENS : These two head of states— Konrad Adenauer, who was the Chancellor of Germany. And these two had not a common background, but they had some important elements in common. First of all, they were both Catholic, and they both fought, in a way, against Nazi Germany. De Gaulle militarily, and Adenauer as a critic against— He was imprisoned. He was the mayor of Cologne, and he was pushed away by the National Socialists.

And also, Adenauer was speaking French. So there was a kind of also personal relationship which they could build on. And then in ’62, de Gaulle wrote a letter to Adenauer to invite him to France. And he invited him personally. Charles de Gaulle did that personally. He thought about, how could I introduce Adenauer after these two wars? How could I introduce the German chancellor in France to pave the way for future political collaboration?

And he wrote him—and this is a very moving letter—that, you know, “I would like you to come to Paris, and I will pick you up at the airport. And then we’ll drive through the city. And then we have political talks. And I will go with you through the city. And then you go to Bordeaux, to another city, and you go to Rouen. And I will arrange that you meet important political people. And I will organize that you will be seen. And when we have done this, we will go for the next step.” And they did that, exactly that.

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] Yeah. And it culminated at Reims?

GAEHTGENS: After this event, they met at Reims. And they went together in Reims, to participate in a mass. And then they met and they had a dinner or a lunch at the Mairie of France.

CUNO: City Hall.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah, at the town hall. And then from there, a couple of months later, they met again in Paris and they signed the treaty, the so-called Élysées Treaty, which is the basis of political collaboration, and also an important treaty to bring the French and the German youth together, and to make exchanges of the next generations. And this is, in a certain way, the basis of the German-French collaboration.

The other European countries were first a little bit irritated about this, because they were not really included in this process. But it was an important, very important, first step in the direction of the European community which we have now. And Reims, as you said, it got another symbolic attachment. It was not only the coronation church anymore; it had now this awful history of the shelling and First and Second World War, but it now became also a symbolic monument of the German-French reconciliation. In Reims newspapers, you could read later, in later years, that Reims now becomes the capital of the French-German reconciliation.

All the states and all the presidents of Germany and France since this event, at some point in their career, went to Reims, either to participate in a mass or they went there to celebrate, only outside. They go to Reims once since.

CUNO: And it continues. In 2011, the esteemed German art historian, your very good friend, Willibald Sauerländer, [Gaehtgens: Yeah] gave the ceremonial address on the cathedral’s 800th anniversary.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah.

CUNO: What did he say?

GAEHTGENS: Well, he was talking about the symbolic moment of the coronation of the French kings and the role of Reims in this political process.

CUNO: And it was important that he was a German who was invited to come give that address.

GAEHTGENS: In a certain way, that was a very warm gesture of the French art historians reaching out to German art historians to say, you know, now it’s time that we investigate and do our scholarship together, and not forget about the past, but confront this past in the right way.

CUNO: And then it continues yet even further when, four years later, 2015, almost a hundred years after the attack on the cathedral, the foreign ministers of France and Germany dedicated a series of stained glass windows by the German artist Imi Knoebel.

GAEHTGENS: Yeah, that’s a wonderful gesture, too, you know, to invite Imi Knoebel, who’s a great artist. And he designed the glass windows, which are wonderful. They, in a certain way, reconstruct the glass windows of the Middle Ages, but not in a literal way. They are shimmering pieces together, you know, it—you have these two elements. On the one side you have the light of the Medieval glass windows; and at the same time, they recollect and recall what happened to the predecessors.

They recall the destruction and the reconstruction. And so it is a great gesture, also, to invite a German artist to do that.

CUNO: Yeah. And now you, a German art historian, are writing this book published on this occasion, the 100th anniversary of the end of the war.

GAEHTGENS: [over Cuno] You know, I was especially interested in the fact, what kind of charisma one monument can have through centuries, and how this symbolism of a monument changes, and that the monument survives with all this past and all this history, and how important it is that we take care of this message and that we conserve these kinds of monuments and protect these kinds of monuments. You know, we have in our current times, if you think of the Near East, these destructions of very important historical monuments by fanatism[sic].

And it goes on, that these destructions take place. And my story here is, in a certain way, a very interesting story because it continues. It goes until our present, and has still, also, an emotional value between France and Germany, which is, in a certain way, conveyed through this story.

CUNO: Well, it’s a great story Thomas, and it’s told very well, so thank you for the book. We’re proud, at the Getty, to be publishing this book. It’s going to appear simultaneously in France, Germany, and the United States. So we’re grateful to you for your time on this podcast, but ultimately, for the work you did on this book. So we thank you.

GAEHTGENS: Thank you very much.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

THOMAS GAEHTGENS: What the reasons are, nobody cares then. You know, the fact that Reims Cathedr...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.