Over the next few months, we’ll be exploring the musical legacy of Sunset Boulevard. Discover more from 12 Sunsets: Exploring Ed Ruscha’s Archive.

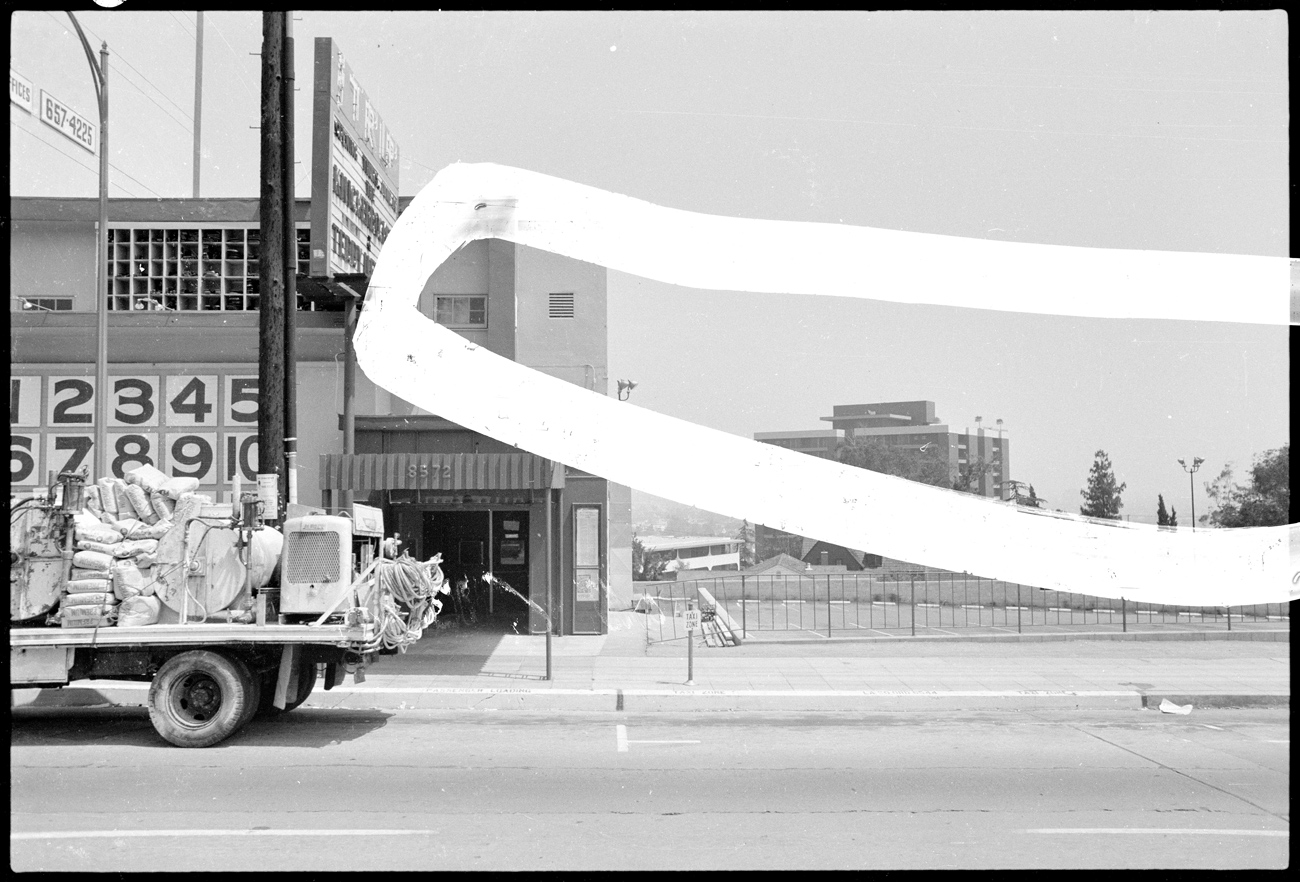

The Trip, 1966, Ed Ruscha. Negative film reel: 8486 headed west (Image 0048). Part of the Streets of Los Angeles Archive, The Getty Research Institute. © Ed Ruscha

As you listen to Ella Fitzgerald sing “Take the ‘A’ Train,” try to also listen around it and through it. Listen to the song as it begins—Lou Levy’s piano warming up through the applause—and listen to the final seconds after it finishes, the band in brief repose, the audience enraptured. You can hear the temperature in the room, the warmth of two hundred bodies. You can hear those bodies shuffle and move, tap a loafer or a heel, reach for a glass, light a cigarette, adjust a wristwatch. You can hear light and shadows, the density of air and smoke. You can hear the distance from the bandstand to the first row of bistro tables. You can hear the parquet of the dance floor.

There is the song and then there is the room of the song; there is Ella and Levy and Herb Ellis on guitar, Wilfred Middlebrooks on double bass, and Gus Johnson on drums, and then there is the Crescendo.

Between 1954 and 1965, the Crescendo’s owner, influential radio DJ and concert promoter Gene Norman, recorded dozens of live albums between the club’s Sunset Strip walls. They featured a range of artists and styles that cemented the venue’s reputation for openness and its embrace of Black and Latino musicians. Jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and Art Tatum, Cuban bandleader Machito, Chicano pianist Eddie Cano, exotica imagineer Arthur Lyman, and cabaret provocateur Frances Faye all cut records there. Ella Fitzgerald’s performances in 1961 and 1962 were also captured live, but not for the Crescendo label. They were recorded by Fitzgerald’s manager Norman Granz and released— first as Ella in Hollywood and later as Twelve Nights in Hollywood—on his label Verve Records (an affiliation she makes sure to mention before her rendition of “Witchcraft”).

Fitzgerald first played the Strip in 1955, right down the block from the Crescendo at the Mocambo (as legend has it, the Mocambo’s owner was reluctant to book a serious jazz singer like Fitzgerald, so her friend Marilyn Monroe intervened and helped get her the gig). “I know I make a lot of money at the jazz clubs I play,” Fitzgerald told her press agent in the early 1950s, “but I sure wish I could play at one of those fancy places.”

Black artists and Black audiences were not always made to feel welcome on the Strip, which in the ‘40s and ‘50s was still rife with segregation and at the mercy of an LAPD obsessed with “race-mixing.” When Duke Ellington played Ciro’s in 1945 (he would later play the Crescendo), Billboard announced it as “the first time that any of the swank strip spots have gone in for a high-priced, big-name Negro band,” and yet Ellington was still also warned by the club’s management: “We don’t allow the help to socialize with the guests.”

The Trip, 1966, Ed Ruscha. Negative film reel: 8486 headed west (Image 0047). Part of the Streets of Los Angeles Archive, The Getty Research Institute. © Ed Ruscha

Refusing those color lines was part of the Crescendo’s ethos and its pre-history. Before Norman took it over, it was The Chanteclair, a supper club co-created in the 1940s by jazz singer Billy Eckstine who wanted it to be a space where Black musicians could be reliably booked. The Crescendo carried that desire forward, as did the club it eventually became in 1965, The Trip. Co-owned by Elmer Valentine who also opened the Whiskey a Go Go, The Trip is typically remembered as a cutting-edge rock venue where Barry McGuire, The Byrds, The Velvet Underground and Nico, and Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable Show all held court. (When Ed Ruscha photographed the club in June 1966, New Jersey garage mimics The Knickerbockers and The Ted Neeley Four were on the marquee.)

Yet The Trip’s story is more complex. It opened just weeks after the Watts Rebellion, and soon its stage featured some of the biggest names in Black popular music. Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Miracles, Wilson Pickett, Billy Preston and the Soul Brothers all played there, as did Jackie Wilson, whose legendary ten-night run drew an audience that included both Elvis Presley and James Brown. If there were any live recordings of those shows, you’d be able to listen around them as well, and hear a very different room, one inevitably touched by the heat of a city still very much on fire.

Further Listening

Louis Armstrong: When the Saints Go Marching In (Live at the Crescendo)

Eddie Cano and Jack Costanzo, with Tony Martinez: Tenderly (Live at the Crescendo)

Frances Faye: Frances and Her Friends (Live at the Crescendo)

Dear Mr. Kun,

Your piece was wonderfully engaging on so many levels. Three times thank you for portraying the racial history behind the Ruscha image. Thank you for engaging the senses to place us in the room. Thank you for a vast knowledge of club owners, musicians and race history of Los Angeles.

I am a docent at the Getty Center and led school tours on Wednesdays. As a complete newbie I was just getting into the swing with the collection, when we closed down. I would weave the kind of story you tell into the tours. Yes it’s great art and it also has an equally great, ever expanding story to be told.

Good Wishes,

Janice Ramkalawan

Ps. I’m going to take a deeper dive into your article and it’s references. if I have any questions can I send them to you if you are available?