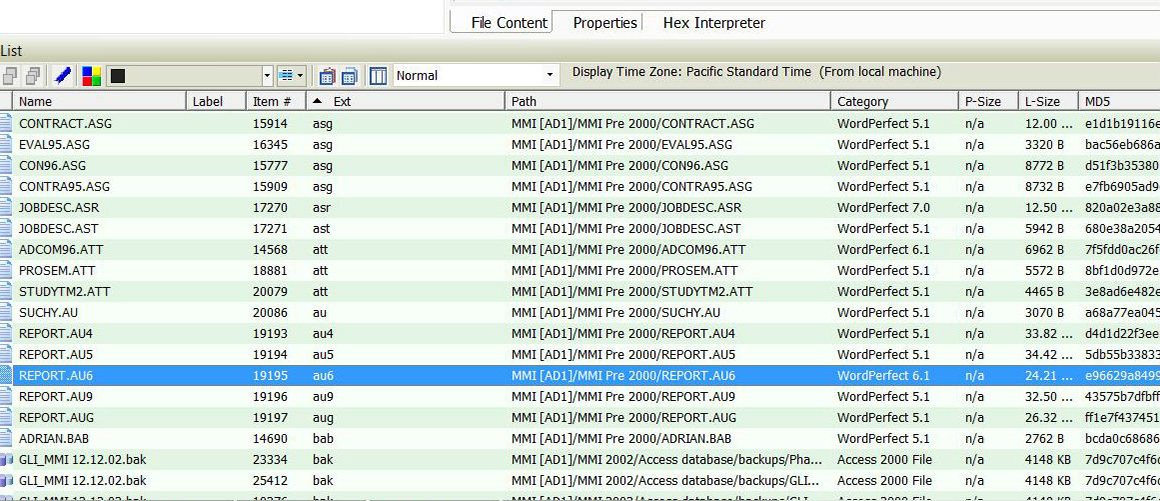

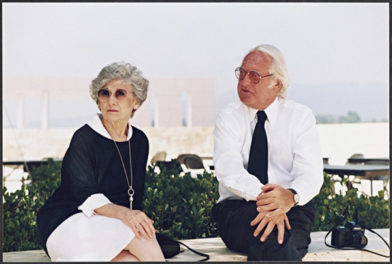

Metadata czars Jonathan Ward and Teresa Soleau of the Getty Research Institute.

Metadata is a common thread that unites people with resources across the web—and colleagues across the cultural heritage field. When metadata is expertly matched to digital objects, it becomes almost invisible. But of course, metadata is created by people, with great care, time commitment, and sometimes pull-your-hair-out challenge.

Here at the Getty we have numerous colleagues dispersed across various departments who work with metadata to ensure access and sustainability in the (digital) world of cultural heritage—structuring, maintaining, correcting, and authoring it for many types of online resources. Several of us will be sharing our challenges and learnings in working with metadata.

Got your own to share? We’d love to swap questions, notes, tips, and resources. Leave a comment.

In the series:

- Jonathan Ward on bridging gaps between library staff and IT (October 17)

- Matthew Lincoln on making meaning from uncertainty (October 24)

- Teresa Soleau on providing access to digital material with metadata (October 31)

- Kelsey Garrison on embracing technological change (November 7)

- Ruth Cuadra on embracing Linked Open Data (November 7)

- Kelly Davis on the importance of data clean up (November 14)

- Melissa Gill on GLAMs’ role in supporting researchers (November 21)

- Krystal Boehlert on the curse of ambiguous metadata (November 28)

- Alyx Rossetti on the human dimension of metadata (December 5)

- Laura Schroffel on digital preservation (December 12)

- Greg Albers on digital publications and SEO (December 19)

- Final thoughts

I’m a researcher and editor of metadata content in the Getty Vocabulary Program. The Vocabularies are structured metadata of researched, fielded information that describes art and architecture, geographic places, and people connected to art. The image below visually describes what we do: linking art-related terms, people related to art, works of art, and any geographic place connected to artwork, through hundreds of semantic links in our controlled vocabularies.

Our vocabularies grow because of large contributions from numerous institutional partners. Naturally, one of the biggest and most complex challenges is data mapping. Our IT team has built a loader for our partners’ data sets, which matches their data fields to our own, and which produces a list that includes new records for inclusion in the vocabularies, near-merges (which need a human eye for confirmation), and complete merges with existing terms. This project needs editorial oversight at every level, because each data load from one of our partners might require new parameters, or sometimes new rules. As we all know, institutional databases are often wildly different, and we pride ourselves on having highly structured data.

Another issue that interests me is the changes in skills and job roles necessary to make metadata repositories truly useful. One of the potential benefits of linked open data is that gradually, institutional databases will be able speak to each other. But the learning curve is quite large, especially when it comes to integrating these new concepts with traditional LIS concepts in the work environment.

There are also many unknowns. A challenge the field faces now is bridging the gaps between IT and traditional library staff, but what forms that will take is still unclear. Will traditional library staff eventually be able to write SPARQL queries to access information for users? Will scholars and patrons be able to do this themselves?

—Jonathan Ward, Data Standards Editor, Getty Vocabulary Program

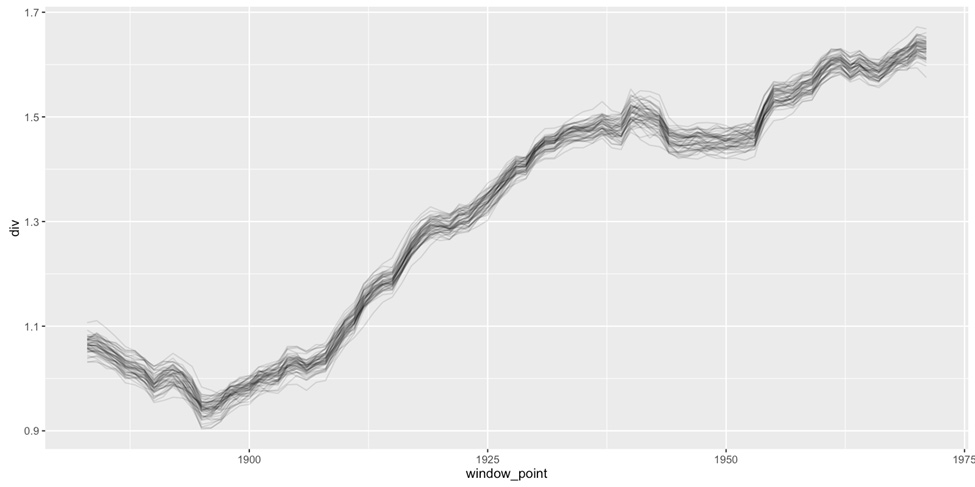

Graph using data from the Getty Provenance Index showing the diversity of genres handled by art dealer M. Knoedler & Co. over time.

I’m the first data research specialist at the Getty Research Institute; I came here after getting my PhD in art history, studying the social networks of Dutch and Flemish printmakers using computational methods. I’ll bring those same methods to bear on data about historical art auctions, dealer stock books, and collector inventories in the Getty Provenance Index to unearth new patterns in how artworks have been bought and sold over the centuries.

Statistics and history deal with a lot of the same questions: How do we find and describe relationships between things? What care do we need to take when our sources are incomplete or ambiguous? How can we identify general rules while respecting unique contexts? Even though these disciplines share similar questions, their worldviews can sometimes feel miles apart. Today many scholars in the digital humanities are working to synthesize these approaches.

A core challenge in working with metadata in the digital humanities is that often times our historical sources are missing or incomplete. This presents a problem for a lot of quantitative data methods, as they’re built to work with complete cases. We are working on different ways to address this problem. Though it’s impossible to magically recover information that just isn’t there (a dealer records selling a work of art, for example, but doesn’t write down the price), we can try to account for how much uncertainty that “known unknown” should add to the conclusions that we come up with.

So how do we go about visualizing all this uncertainty? In the plot shown above, we wanted to characterize the diversity of genres that art dealer M. Knoedler & Co. was selling at different points in time. Because some entries in our records are missing either a genre, a sale date, or both, we might assign values through randomized (but educated) guessing. Do this fifty times, and we get fifty slightly different timelines, rather than one “definitive” answer.

The fuzziness of this visual is evocative to be sure, but it also helps us understand the discrete range of possible results we might get were we to have complete data. In this case, an overall trend still shines through this added uncertainty: Knoedler began to offer an increasingly heterogeneous array of genres between 1900 and 1925. But smaller, short-lived spikes in some of these timelines (like those around 1940) are not present in every iteration, suggesting that we ought not to build important conclusions on what is likely a spurious blip in our quantitative results. (See more here about how this kind of diversity is calculated.)

Another really complex and interesting problem is creating a data model that covers all the different ways that works of art can change ownership—auction sale, private exchange, bequest, even theft!—and all the associated bits of information that go along with those transfers—prices paid, dates sold, or current locations. Luckily, several different institutions are all thinking about how to tackle it. Two ongoing projects related to our work here at the Getty are the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Art Tracks initiative that will create a model for describing the history of their artworks’ individual and institutional owners, and the holes in those histories. The American Art Collaborative aims to interlink the collections data of fourteen different museums in the US so that they can link to each other, and also (hopefully) to related data sources, like the records of art transactions we have in the Provenance Index.

Another really complex and interesting problem is creating a data model that covers all the different ways that works of art can change ownership—auction sale, private exchange, bequest, even theft!—and all the associated bits of information that go along with those transfers—prices paid, dates sold, or current locations. Luckily, several different institutions are all thinking about how to tackle it. Two ongoing projects related to our work here at the Getty are the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Art Tracks initiative that will create a model for describing the history of their artworks’ individual and institutional owners, and the holes in those histories. The American Art Collaborative aims to interlink the collections data of fourteen different museums in the US so that they can link to each other, and also (hopefully) to related data sources, like the records of art transactions we have in the Provenance Index.

—Matt Lincoln, Data Research Specialist, Digital Art History

A peek under the digital collections hood for a photograph by Shunk-Kender of Andy Warhol in a hotel, Paris, May 8–9, 1965. The Getty Research Institute, 2014.R.20

My job is to oversee the Getty Research Institute Library’s technology systems, and to support the adoption and integration of emerging technologies and digital initiatives, in order to facilitate research and to preserve our collections. That work looks different every day, but a lot of it involves massaging, analyzing, and mapping data or metadata from one format, system, or standard to another.

For many of our digital collections, the final resting place is our digital preservation repository, built using Rosetta software. Descriptive and structural information about the resources we digitize is pulled from many sources, including our collection inventories and finding aids, library catalog records, legacy databases, and spreadsheets we sometimes receive along with archives. Information also comes from the physical materials themselves as they are being reformatted—for example, in the form of handwritten annotations on the backs of photographs or labels on videotapes, which are then transcribed. Metadata abounds.

Even file names are metadata, full of clues about the content of the files: for reformatted material they may contain the inventory or accession number and the physical location, like box and folder; while for born-digital material, the original file names and the names of folders and subfolders may be the only information we have at the file level.

One of the biggest challenges we face right now is that our collection descriptions must be at the aggregate level—or we’d have decades of backlogs!—while the digital files must exist at the item level, or even more granularly if we have multiple files representing a single item, such as the front and back of a photograph. How do we provide useful access to so much digital material with so little metadata? Thousands of files to click through can be overwhelming and inefficient if the context and content isn’t made easy to recognize and understand.

We have definitely not solved this problem, but we’ve addressed it when we can. For example, right now we’re working on a project to use artwork titles from the Knoedler Gallery stockbook database (part of the Provenance Index) to enrich a part of the collection inventory that contains about 25,000 photographs of the dealer’s art stock, listed only by stock number. After we digitize these photographs, we’ll be able to say, for example, “A street in Paris, with figures” instead of “A3922”—which will make these materials much easier to use! Plus, anything that makes the material easier to use now will contribute to the long-term preservation of the digital files as well; after all, what’s the point of preserving something if you’ve lost the information about what the thing is?

There is also technical information about the files themselves to consider and preserve such as file format versions, file creation dates, and checksums—fingerprints of the file that helps us verify the file hasn’t changed over time—as well as event, or provenance, information so you can track what has happened to the files since they came into the custody of the archive.

Another development in the field that interests me now is the movement toward software preservation, such as the Software Preservation Network, but the field is also recognizing that that digital preservation must be a cooperative, community effort. Just as librarians learned long ago that it didn’t make sense for each library to catalog every single book—and thus was born the union or cooperative catalog—digital preservationists are working out who should be responsible for preserving which software. There’s even talk of something called “emulation as a service,” where a software environment is replicated virtually, allowing you to load all kinds of files without having to install each piece of software on your machine. So many preservation challenges yet to be solved! And we may not know whether or not we were successful until many decades into the future!

Another development in the field that interests me now is the movement toward software preservation, such as the Software Preservation Network, but the field is also recognizing that that digital preservation must be a cooperative, community effort. Just as librarians learned long ago that it didn’t make sense for each library to catalog every single book—and thus was born the union or cooperative catalog—digital preservationists are working out who should be responsible for preserving which software. There’s even talk of something called “emulation as a service,” where a software environment is replicated virtually, allowing you to load all kinds of files without having to install each piece of software on your machine. So many preservation challenges yet to be solved! And we may not know whether or not we were successful until many decades into the future!

—Teresa Soleau, Head, Library Systems & Digital Collections Management, Getty Research Institute

From print catalog to searchable record: An entry in a German sales catalog for a Rembrandt drawing is scanned, OCR’d, added to a spreadsheet for processing, and then transformed into a searchable database record.

Having been a part of several different projects for the Getty Provenance Index, I am particularly familiar with the inherent complications of working with historical data. Currently I am working on the second phase of the German Sales Project, which uses digitization, Optical Character Recognition, and a custom Perl program to take data from digitized auction catalogs of the 1930s and ‘40s and move them into Excel spreadsheets that are then imported into a database.

Considerable advances in OCR quality mean we spend less time hand-touching the raw text to correct it against the originals. However, for OCR we are still limited to using catalogs with very basic fonts—handwritten notes and stylized fonts are completely unreadable and require full transcriptions by hand. Even greater advancements in character or word recognition would improve on the process of transcription, which is already vastly faster than it was just a few years ago.

One unavoidable problem is inconsistency in the catalogs’ formatting. This means we have to build flexibility into our code to be able to recognize pertinent data, however it happens to be presented. Pre-processors “massage” the text, modifying the format of the raw data to conform to the needs of the Perl main program, which then analyzes blocks of text in order to identify data elements. Main then generates an Excel spreadsheet that preserves the verbatim descriptions and parses out the data elements into any of 26 categories.

For our current, second phase of the German Sales Project, we programmatically add live Excel formulas to our spreadsheets that activate based on keywords or phrases found in descriptions. As editors correct OCR-introduced errors (e.g., misspellings, typos) in keywords, linked columns containing the formulas automatically populate with the appropriate da ta. This feature helps editors speed up the process of parsing and standardization, and it has led to more data-rich spreadsheets (and therefore, more complete records being imported into the database).

ta. This feature helps editors speed up the process of parsing and standardization, and it has led to more data-rich spreadsheets (and therefore, more complete records being imported into the database).

Flexibility is key when working with historical data sources. Recognizing problems and seizing opportunities require us to constantly adapt our code and to augment it whenever and however inspiration strikes. It also means being willing to change processes and to embrace new technologies as they emerge.

—Kelsey Garrison, Metadata Assistant, Collecting and Provenance Department, Getty Research Institute

I started my career working for a small database software company just as the world of online databases and big mainframe search systems was coming to the fore. I’ve been designing databases and working to organize and standardize data for more than three decades, as well as doing database software quality assurance, documentation, and training.

In 1984 the Getty Research Institute selected STAR, the database system my company developed, for the Getty Provenance Index. I helped with the data design for the Provenance Index, which is a family of structured databases collectively containing over 1.5 million records about the ownership of artworks from archival inventories, auction catalogs, and dealer stock books.

In 2007 the GRI was looking for someone to manage STAR in-house. I knew STAR inside and out, and studied art history at UCLA, so it was a dream job for me to combine my interests and apply my knowledge about the Research Institute’s use of STAR to help move their data projects forward.

Now I’m involved in a very large, multi-faceted project to remodel and publish the Provenance Index as Linked Open Data (LOD). This process involves studying how different data elements relate to each other and mapping them to a new “semantic” data structure. An example can illustrate the shift from the type of flat database record we’ve been using to a semantic representation of the same data. Let’s choose Irises, the painting by Vincent van Gogh from the Getty’s collection:

Semantic data structure for Vincent van Gogh’s painting Irises (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 90.PA.20)

The data “triples” on the right represent the semantic relationships between the Painting (“Irises”) that was “created by” the Artist “van Gogh” and that the Painting (“Irises”) was “created in” the year “1889”. New software for the remodeled Provenance Index will present this semantic data in ways that support the traditional provenance researcher as we have always done, but also open the door to art market research driven by “big data.” What will it look like? How will it work? There are many open questions that will gradually be resolved as the project progresses.

It’s been fun to study the workings of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model and figure out how to use it to map our data. There is a wonderful community of people working on similar projects at other museums and libraries around the world, all with the goal of presenting a unified, standardized, and linkable collection of cultural heritage data. I’m glad to be a part of it!

—Ruth Cuadra, Business Applications Administrator, Information Systems, Getty Research Institute

I began my career at the Research Institute as the graduate intern in the Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance, transcribing and then editing the Knoedler Dealer Stock Books database. Now I’m the research assistant for the department, as well as liaison to the Provenance Index remodel project Ruth described last week.

My focus right now is identifying problematic issues that have developed since transcription, and fixing them so the data is standardized for the upcoming GitHub release, for data analysis projects, and for mapping to Linked Open Data. This requires a lot of multi-tasking and coordination with a variety of stakeholders and departments. So many of the issues we find are tip-of-the-iceberg—they reveal something much more complicated underneath. I work very closely with our research data specialist and database admin on the metadata cleanup. I also work a lot with the project manager for the remodel on administrative documentation tasks.

The most important thing when cleaning this kind of metadata is a thorough understanding of the content. A lot of people are technologists but not art historians, and vice versa. To do this kind of work, you really need a foot in both camps. I usually begin with the source material, where one needs an intimate understanding of the history of art and of the art market of the 20th century to contemplate the various implications of what was recorded. Then I use my background in library and information science to conceptually represent that information in accordance with internal and external rules. I use both traditional resources like AKL, ProQuest, and the Research Institute’s archives for my research, and follow a number of other organizations doing similar work, like the Carnegie Museum of Art, for emerging conversations about provenance metadata.

The image above shows just one small example of the importance of data cleanup. In a few cases, a parent and child with the same name both purchased artwork from Knoedler. This makes it difficult to determine which person was actually involved in the transaction. Doing research to answer this question ensures the reliability of our information, and ensures that the data we release and map to the semantic web will be accurate. That research can become very involved very quickly, however, and as with any other research, must be documented as we continue forward.

Looking ahead, I’m really excited about the promise of Linked Open Data, and see immense possibility with that for provenance data specifically. Provenance has traditionally been a very closed-off field, where access to the information needed for research is difficult or impossible to obtain. The Getty remodeling the Provenance Index to LOD, will, I hope, be a signal for others to be more open with their provenance data.

We have a few major challenges on our plate right now, and we’re just starting this process. The main problem we’re running into is the sheer scope and scale of some of the cleanup tasks we’ve identified. Recently the database admin and I calculated approximately 1,600 hours of work, and that’s only for two databases. The Provenance Index contains many more, and each database has a specific set of requirements and varies in size. Resource allocation and prioritization of tasks are some decisions that need to be made over the next few weeks.

In this field, there’s still a sense of grappling with how to do the work that we do, or what it is exactly. For example, what is the meaning of the Provenance Index, existentially? Are we simply a digital record of historical materials, or more? What is the role of the editor in creation of these resources? How much work should we do and make explicit, and how much work is the responsibility of the researcher? There are many big, high-level questions, and we often bring in specialized experts for these kinds of discussions.

In this field, there’s still a sense of grappling with how to do the work that we do, or what it is exactly. For example, what is the meaning of the Provenance Index, existentially? Are we simply a digital record of historical materials, or more? What is the role of the editor in creation of these resources? How much work should we do and make explicit, and how much work is the responsibility of the researcher? There are many big, high-level questions, and we often bring in specialized experts for these kinds of discussions.

—Kelly Davis, Research Assistant, Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance

How Can GLAMs Support Humanities Researchers Working with Data?

Melissa Gill, Getty Research Institute

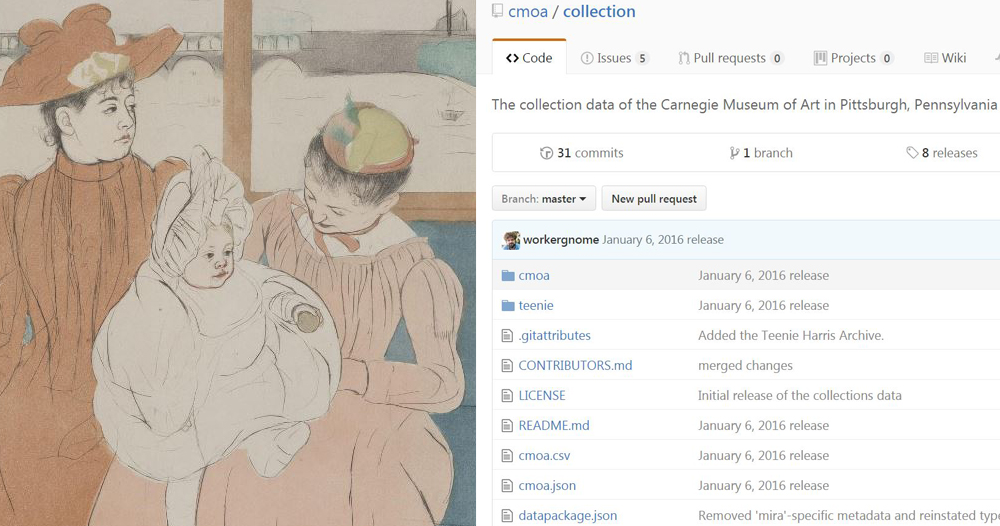

Mary Cassatt’s print In the Omnibus (50.4.1) from the Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection, and their GitHub data repository.

I’ve worked in several metadata positions here at the Getty Research Institute—as a graduate intern with the Getty Vocabulary Program, a research assistant on the Knoedler Stock Books project for the Getty Provenance Index, and now as project manager for the Getty Provenance Index Remodel (PIR) project, the same one that Kelly, Matt, and Ruth are working on.

My background in metadata has been beneficial here, since the PIR requires us to work through issues in mapping and publishing the Getty Provenance Index data as Linked Open Data. Another important aspect of the project is careful consideration of metadata needs for art historians and 21st-century scholarship at large, which is where my background in art history comes in handy.

As scholarship becomes increasingly digital, art historians’ knowledge areas are expanding to include data management and programming skills conventionally reserved for technologists and information professionals. As part of the Digital Art History team at the Research Institute, my colleagues and I are interested in fostering innovative art-historical research and scholarship through the advocacy for and use of tools and practices associated with the burgeoning field—and asking key methodological and pedagogical questions about the needs of scholars who use them.

For example, what skills and resources do art historians need in order to create, manage, share, and preserve metadata for their research and scholarship? What roles should the galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM) community play to cultivate resources and services to address these needs? These might include producing resources for metadata design and data standards for scholarly audiences, producing tools for leveraging existing metadata resources for managing personal research materials, like tools developed by the Visual Resources Association Embedded Metadata Working Group, structuring and publishing collections and research datasets with documentation that support computational or data-driven methodologies, like the Carnegie Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art collection datasets on Github, and developing citation models for data scholarship in the humanities.

Many of these aims can be accomplished through cooperative, community-driven efforts, but individual institutions must also contribute. Unfortunately though, because projects that incorporate these aims are often laborious and require very specialized knowledge, persuading institutions to take them on is sometimes a challenge.

Luckily, the Getty Research Institute is leading by example; the Provenance Index Remodel project aims to deliver not just a new technical infrastructure for the Getty Provenance Index databases, but also to develop resources for scholars to use the data effectively, such as best practice recommendations for using and sharing datasets, and better documentation about our data. Based on needs expressed by Getty Provenance Index users, we have decided to release on GitHub select full datasets from the Getty Provenance Index with documentation and an open data license so that scholars can conveniently access raw data in the early stages of the project. The PIR project is a huge undertaking. And because of the content of the Index and the challenges the remodel poses for digital art historians, it is an essential one. Each of these challenges is an opportunity to further the field by innovating new resources and practices for humanities researchers working with data.

Luckily, the Getty Research Institute is leading by example; the Provenance Index Remodel project aims to deliver not just a new technical infrastructure for the Getty Provenance Index databases, but also to develop resources for scholars to use the data effectively, such as best practice recommendations for using and sharing datasets, and better documentation about our data. Based on needs expressed by Getty Provenance Index users, we have decided to release on GitHub select full datasets from the Getty Provenance Index with documentation and an open data license so that scholars can conveniently access raw data in the early stages of the project. The PIR project is a huge undertaking. And because of the content of the Index and the challenges the remodel poses for digital art historians, it is an essential one. Each of these challenges is an opportunity to further the field by innovating new resources and practices for humanities researchers working with data.

—Melissa Gill, Digital Projects Manager, Digital Art History

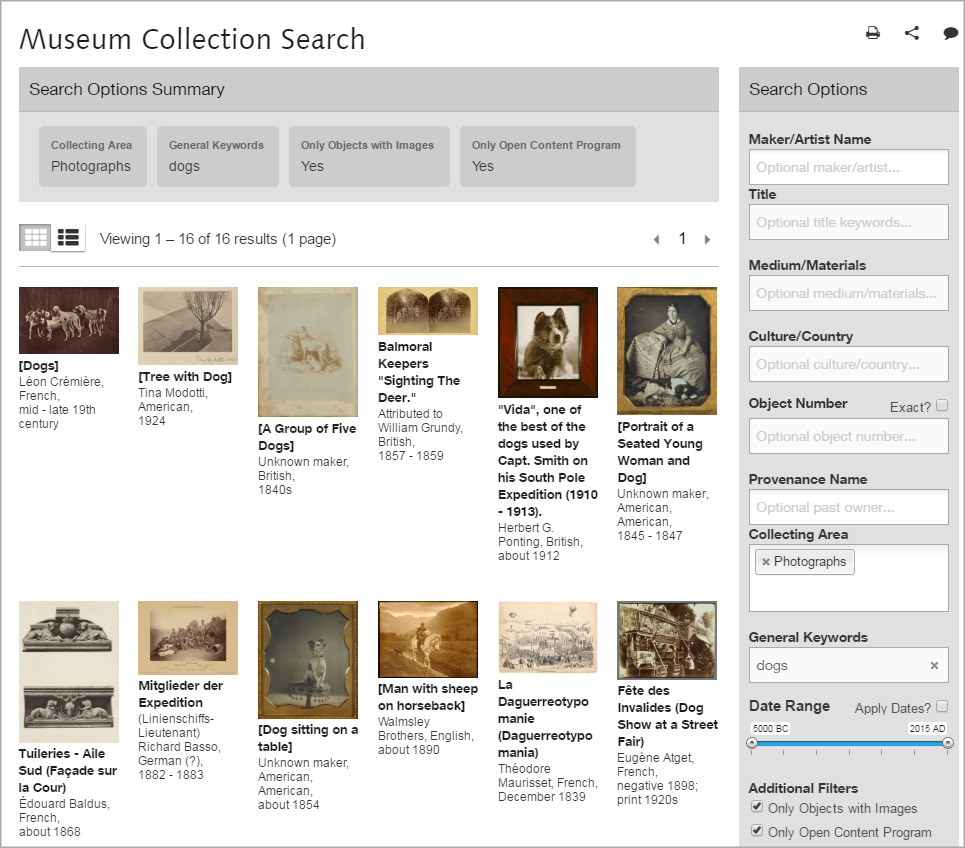

One of the many applications of accurate metadata: identifying public-domain dog photographs in the Getty Museum’s collection

I work in the Getty Museum’s Collection Information & Access (CI&A) Department. I create metadata in our collection information database for new photography of artworks so digital images are available for Open Content (rights-free, high-res downloads), internal use, mobile apps, and everything in between.

Matt wrote about the challenges of incomplete or ambiguous data. This can make research difficult—but it also applies to making information accessible in the first place. In the past, the metadata we tracked for images sometimes had multiple meanings. This, coupled with legacy software dependencies and workflows, caused us to reevaluate how we were tracking and using our data. For example, we didn’t have a way to say an image was copyright-cleared but was not quality-approved for publish (or vice versa). And what happens when copyright data changes?

Manually updating such fields was quite time-consuming and prone to error. It wasn’t until the Open Content Program began that we in CI&A took a long hard look at all the variables and determined we needed to separate the information, and translate business rules into algorithms for programmatically determining usage clearance.

In 2012 our department began evaluating our data in preparation for launching the Open Content Program. We needed a way to efficiently and accurately release images for download based on several criteria. Ultimately we separated out three filters that were previously intertwined: Rights, Image Quality, and Approval for Public Access. Because these fields are separate, they can operate individually, allowing for more granular permissions and access. Obviously we want to default as much as possible to Open Content, making exceptions for images of insufficient quality or that we aren’t ready to show.

Rights are managed by the Registrar’s Office and include copyright, lender or artist agreements, privacy restrictions, etc. Object rights are managed at the object level in the database, not to be replicated and maintained in the media level of the database. Any media-specific copyright, used infrequently for images not made in-house, can be added at media level. For example, an image supplied by a vendor for a new acquisition might be published online before the object can be scheduled for photography in our studios. While the object is cleared for Open Content download, the vendor image would not be cleared for download and the metadata would reflect this. Within the media metadata, there is a field that denotes image quality and another that allows for approval by curators of what gets published to the online collection pages.

The Imaging Services team determines Image Quality at the media level. Most born-digital images are approved, but the older photography gets a closer look. Another example would be that recent high-quality studio photography would be published online, but iPhone snapshots in a storeroom would not.

Curatorial and conservation departments give Approval for Public Access, deciding which views should represent their objects online, also at the media level. This might include allowing preferred representations, restricting technical views and conservation work in progress.

Another challenge in making images accessible is creating relevancy in the digital image repository used by Getty staff. We need a consistent way to use data to identify what’s relevant, and that varies per user. When searching for images of an object in this repository, there are often several pages of image thumbnails to sift through. The faceted search is great, but only gets us so far. How do staff know which image is the most recent/best/preferred? Is there a way to demote older, less desirable images so that choosing the right image for a press release or blog post is easier?

We want older photography to still be available—for curators and conservators it’s a valuable record for condition reports, conservation, and study. But we don’t want the new, beautiful photography missed because it’s hard to find; such images are highly relevant for communications or publications staff. Imaging Services would be best at filtering images for various purposes—so we need a data field that reflects this. It may or may not fall under the Image Quality bucket, but we’re still undecided as of now.

The thing I’m most concerned with is doubling up meaning on a single metadata field. We’ve been down that road before! We already use the Image Quality field to describe if something is born digital or needs a closer review. If we include a qualifier for “most recent/preferred,” will that get tangled with other fields or alternate interpretations in the future? Adding a new image should not require an audit of all known media. Is this something that can be programmed into our workflow to update automatically?

The thing I’m most concerned with is doubling up meaning on a single metadata field. We’ve been down that road before! We already use the Image Quality field to describe if something is born digital or needs a closer review. If we include a qualifier for “most recent/preferred,” will that get tangled with other fields or alternate interpretations in the future? Adding a new image should not require an audit of all known media. Is this something that can be programmed into our workflow to update automatically?

This refinement of data-driven image access is an ongoing collaboration between my department and the Getty’s ITS department. The end goal is to make our images easily accessible through Open Content, internal use, or otherwise. That can only be achieved through clean and meaningful metadata. The definitions of fields and values should as unambiguous as possible, which is hard to do with so many stakeholders and intended uses!

—Krystal Boehlert, Metadata Specialist, Collection Information & Access

A peek under the metadata hood of the Getty Research Portal, which aggregates digitized art history texts.

I’m a software engineer in the Information Systems Department of the Research Institute, but I came to this position via a very unusual path. I started my career at the Getty as a graduate intern in the Vocabulary Program in 2012–2013. When my internship ended, I was hired into a temporary metadata librarian position. One of my main responsibilities was to work on the Getty Research Portal, and as my work became more and more technical, I started learning to program. Eventually, my job was made permanent and I was re-classed as a software engineer.

In my current role I work on numerous projects and applications built in-house to provide access to the Research Institute’s collections. Because of my unique background and because I have an MLIS degree, I am almost always involved in the metadata mapping and transformation portions of a project and I work mostly on the back end. I am still very much involved with the Getty Research Portal; that project is unique in that we act as an aggregator of bibliographic metadata for digitized art history texts from institutions all over the world.

As part of the recent Portal 2.0 launch, we decided to start over from scratch with the metadata mapping and transformation. Because we accept metadata in several different formats (MARC, Dublin Core, METS, and a soon-to-be-implemented custom spreadsheet), mapping and normalizing data can be quite a challenge. For Portal 2.0, we decided to map all of these different source records to Qualified Dublin Core so that we would have a standardized set of Getty Research Portal metadata records that could be shared back to the community.

I wrote transformation scripts in Python for each metadata standard, but in most cases new contributions must still be carefully reviewed to check for anomalies and differences in implementation (particularly with the notoriously ambiguous but seductively simple Dublin Core standard). Additionally, as much as we tried to stick to Qualified Dublin Core, we found that we needed to add a handful of local fields to simplify faceting and display on the front end of the application.

The Getty Research Portal is a great example of the challenges posed by metadata aggregation. This is a problem that affects almost everyone in the library community in some way, whether you are a metadata contributor, a service provider, or even if you are just trying to aggregate internal data.

Despite all of the standards available, metadata remains MESSY. It is subject to changing standards, best practices, and implementations as well as local rules and requirements, catalogers’ judgement, and human error. As library programmers, we and others in the community are constantly looking for new, interesting, and useful ways to repurpose metadata. We work to automate metadata transformations as much as possible, but for now at least, these processes often still require a human eye.

Despite all of the standards available, metadata remains MESSY. It is subject to changing standards, best practices, and implementations as well as local rules and requirements, catalogers’ judgement, and human error. As library programmers, we and others in the community are constantly looking for new, interesting, and useful ways to repurpose metadata. We work to automate metadata transformations as much as possible, but for now at least, these processes often still require a human eye.

—Alyx Rossetti, Software Engineer, Information Systems

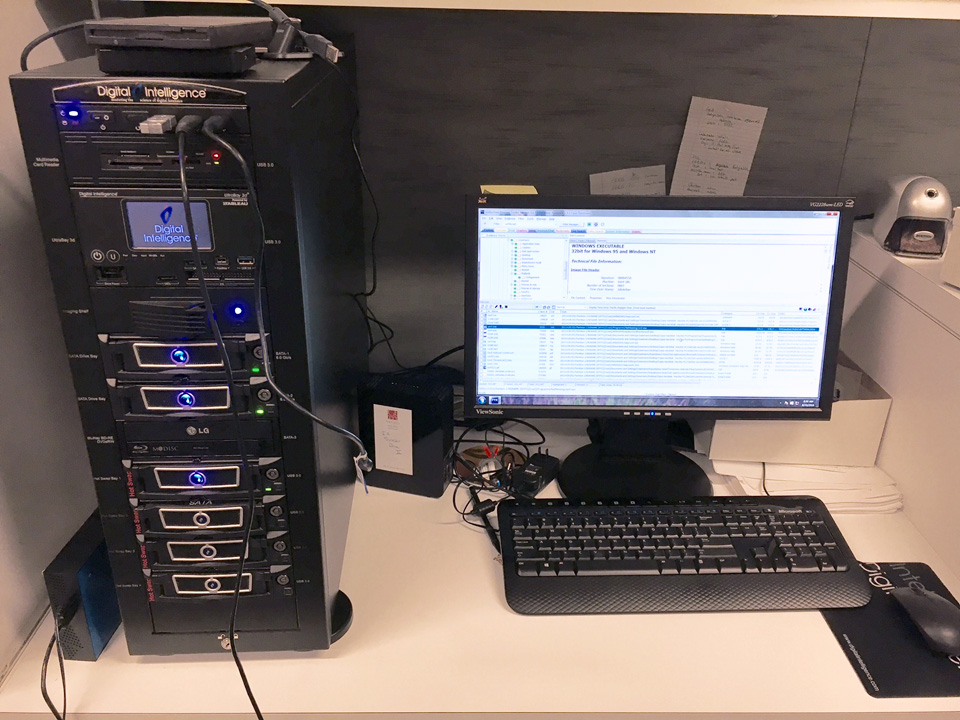

FRED, the Forensic Recovery of Evidence Device, is used to discover and convert born-digital files

As the digital archivist in special collections, I process born-digital content received with our archival collections. Most of the born-digital material I work with exists on outdated or quickly obsolescing carriers including floppy disks, compact discs, hard drives, and flash drives. I transfer content from the obsolete media into our digital preservation repository, Rosetta, and provide access to that content through our integrated library system, Primo.

File extensions are a key piece of metadata in born-digital materials that can either elucidate or complicate the digital preservation process. Those three or four letters describe format type, provide clues to file content, and even signal preservation workflows that indicate which format a file might need to be converted to after disk imaging and appraisal. Because they are derived from elements found outside of the bitstream itself and can be visually read by a human, file extensions are often referred to as external signatures. This is in contrast to internal signatures, a byte sequence modelled by patterns in a byte stream, the values of the bytes themselves, and any positioning relative to a file. For instance, a Microsoft word document for Windows 95 should have the following internal signature: D0CF11E0A1B11AE1{20}FEFF.

At the Getty, born-digital files are processed on our Forensic Recovery of Evidence Device, otherwise known as FRED. FRED can acquire data from Blu-Ray, CD-ROM, DVD-ROM, Compact Flash, Micro Drives, Smart Media, Memory Stick, Memory Stick Pro, xD Cards, Secure Digital Media and Multimedia Cards.

FRED, along with its software FTK (Forensic Toolkit), is a forensic digital investigation platform originating from the policing and judicial fields. FTK is capable of processing a file and indicating what format type the file is, often identifying the applicable software version. When working with the FTK software, we can easily compare file extensions to format types. However, relying on these external signatures for identification purposes can also present certain challenges. For instance, different versions of the same file may have the same extension but may be significantly altered between file versions. File extensions are also easily manipulated due to human error or automated processes. And file extensions are not standardized or unique, so unrelated file formats can have the same file extension. Additionally, older Macintosh operating systems had different standards which did not require the last letters following the full stop of a filename to include standardized external signatures.

Screen capture showing wonky file extensions in FTK, such as “au6” and “asg,” in the third column from left

While FRED with FTK is an invaluable dynamic system, because it originated in law enforcement, challenges arise when using it to work with cultural heritage objects. One significant challenge is that FTK is not able to recognize file formats for some architectural design software I have been working with.

Screen capture showing missing file extensions in FTK, indicated by <missing?> in the third column from left

There are several other tools available besides FTK to trace a file format with an unreliable extension, and most of them utilize the UK’s National Archives PRONOM project. PRONOM is an online database of data file formats and their supporting software products. Simply type a file extension in the search box and PRONOM will report the name of the software, the version, and often a description for the corresponding file format.

In my work, I validate files using DROID (Digital Record Object Identification), software that runs reports on batches of files. DROID reports will describe the precise format of all stored digital objects, and link the identification to the PRONOM registry of technical information about that format and its dependencies. But PRONOM and DROID are not comprehensive, and

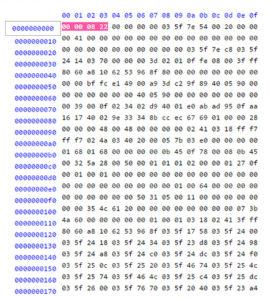

An architecture design file viewed in the hex editor

inevitably one will run across a file lacking a recognizable extension or format information. In one study conducted by the Archives of New Zealand on a set of approximately 1 million files, only 70% of the files could be identified by PRONOM. Sadly, DROID failed to recognize my architectural design files as well.

FTK and DROID analyze files based on their internal signature with automated processes, but if the file types are not recognized by either software’s directory, files will not validate. So when automated processes fail, and when readable file extensions fail or are missing, the next point of access in identifying a file is by manually examining the internal signature. Using a hex editor to analyze the byte stream can reveal the patterns that comprise internal signatures. Luckily, I have been able to recognize a discernable pattern on the byte stream of my architectural design files. But that is only the first step in defining a file format’s internal signature. Extensive research on similar files from varying sources is also required as part of the identification process.

The challenge of identifying file formats and dealing with tricky file extensions will continue to be a burden on the digital archiving community moving forward. Born-digital content continues to proliferate in archival collections as born-digital carriers increasingly become the standard vehicle for collecting practices. It is difficult to steward the long-term preservation of digital objects without understanding their identity and characteristics. However, new contributions to PRONOM are happening regularly and the directory will continue to improve its robustness.

I am encouraged by the many new ways developers and institutions are dealing with the potential loss of data from unrecognizable formats and unreliable extensions. Scholarship can only benefit from these amazing technologies and contributions that are improving discoverability and facilitating access.

—Laura Schroffel, Digital Archivist, Special Collections

Here’s a trick you should know: “View Source.” Using any major web browser, you can view the source code of any site. The code will be more or less legible depending on how the site was built and served to you, but in many cases you can learn quite a lot this way. In Chrome, go to View > Developer > View Source. Try it on our catalogue of Roman Mosaics and you’ll see the sixteen different <meta> tags we included in the publication.

I’m the digital publications manager at Getty Publications but my career started in print publishing. For print books, we’ve long had a standard way of handling book metadata, and it usually starts with the Library of Congress. We send manuscripts of our titles to the LOC as soon as we have clean copies and some weeks later they return to us their official Cataloging-in-Publication data, which is printed on the book’s copyright page and also eventually transmitted to major libraries. About the same time, our marketing department starts work on our seasonal sales catalog. This is when we finalize most book metadata, including page count, trim size, and price. We also write a description for the book and brief bios for its authors, and assign subjects from the Book Industry Standards and Communications (BISAC) list.

All this goes into the sales catalog and is fed to our distributor, the University of Chicago, and from there it’s shared with hundreds of wholesalers, retailers, libraries and others, including our trading partners Amazon and Google. The process is so seamless we rarely ever gave it much thought. That is, until we started publishing digitally and all this metadata machinery, which was built up specifically for print books, proved mostly useless for the online publications we started doing. For these, we needed to start from scratch to find the best ways of sharing book metadata to increase discoverability. Essentially we had to get into search engine optimization, or SEO.

Our first attempt at this was to use <meta> tags. These are special HTML tags that are added to a website (in the underlying code) to add metadata to the site. Each tag contains a name/content pair and like many web publishers we use Dublin Core Terms for naming our metadata items. For instance:

<meta name=”dcterms.publisher” content=”J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles”>

We felt like this was a strong start. We were able to embed all our primary metadata points this way, in a language common to millions of websites. I can’t say for sure it helps with SEO, but it certainly doesn’t hurt and if nothing else it attaches important information about the book to the book itself, which could prove valuable for archiving and for future researchers.

We’re now in the midst of revamping and expanding our SEO and metadata efforts. For starters, we think there are some items we currently share as <meta> tags that might actually be better included as rel (relation) attributes inside other tags. Relation attributes are commonly applied to <a> tags where there is an active hyperlink on the site already, or in standalone <link> tags that only show up in underlying code; either type should be discoverable by search engines and other site crawlers. The rel attribute defines a relationship between the site the tag is on and the page or resource the tag points to. For instance, we used to say with a <meta> tag that the online catalogue also had an EPUB format available like this:

<meta name=”dcterms.hasFormat” content=”application/epub+zip”>

We think it would be better to use a rel attribute inside the EPUB download link that’s already on every page. This indicates that there is an alternate format and that it’s an EPUB type, while also providing a path to it, thus making the human-readable link into one that is, machine-readable as well.

<a rel=”alternate” type=”application/epub+zip” href=”http://www.getty.edu/publications/romanmosaics/assets/downloads/RomanMosaics_Belis.epub”>Download the EPUB</a>

Some common link relations are “canonical,” “next,” “previous,” and “search,” but there are about eighty officially recognized ones to choose from. We’re looking at about a dozen of them to incorporate in every online catalogue going forward. In addition to expanding our use of these relation attributes in <a> and <link> tags, we were inspired by the SEO plugin for Jekyll sites and are also planning on integrating Open Graph protocol tags for Facebook, data formatted for Twitter Summary Cards, JSON-LD formatted site data, and an XML Sitemap. We may also get around to microdata systems like schema.org, and perhaps even incorporating the Getty vocabs, but we also have to leave ourselves time to actually publish some books, so that’s all to figure out another day!

Some common link relations are “canonical,” “next,” “previous,” and “search,” but there are about eighty officially recognized ones to choose from. We’re looking at about a dozen of them to incorporate in every online catalogue going forward. In addition to expanding our use of these relation attributes in <a> and <link> tags, we were inspired by the SEO plugin for Jekyll sites and are also planning on integrating Open Graph protocol tags for Facebook, data formatted for Twitter Summary Cards, JSON-LD formatted site data, and an XML Sitemap. We may also get around to microdata systems like schema.org, and perhaps even incorporating the Getty vocabs, but we also have to leave ourselves time to actually publish some books, so that’s all to figure out another day!

—Greg Albers, Digital Publications Manager

For #MetadataMonday, what began with alliteration ended with illumination. Over a period of three months, colleagues from across the Getty pinpointed what makes their work with metadata rewarding, challenging, and ever-changing. By aggregating this omnibus article (comprising eleven individual metadata-centric accounts in total), several overarching themes of working with cultural and historical metadata emerged:

- metadata has the potential to both obfuscate and expand access to materials;

- working with metadata requires striking a balance between uncertainty, probability, and intense granularity;

- the line between quantitative and qualitative is less distinct than we think; and

- there is both a ghost within and a human behind the machine at all times.

Surprisingly, despite the diversity of practices and materials to which metadata is applied (from SEO for a digital publication, to Linked Open Data, to historic stock books), these themes are relevant to them all.

The messy, human nature of metadata underscores a truth of working in technology across the GLAM world: the tools, content, datasets (etc.) that we make have in them our virtual fingerprint, and it is essential that we acknowledge it. Just as digitizing something doesn’t necessarily make it accessible, working with technology doesn’t automatically erase human error and bias, or universalize human intention. These are truths that continually circulate in the foreground of digital art history, digital humanities, and related fields. Making them part of the larger academic, cultural, and artistic conversation—one of the promises of open-access policies like the one at the Getty—is essential as the line between digital and analog continues to blur. So, while #MetadataMonday is over for now, we encourage you to continue the dialogue both online and off.

—Marissa Clifford, Research Assistant, Digital Art History Group, Getty Research Institute

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks