Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“Photography, historically, has been used to pin people of color in a particular location to a particular identity or stereotype, and the artists in this exhibition work to unpin that.”

Photography is a uniquely accessible and flexible medium today, encompassing everything from cell-phone snapshots to large-format negatives, from formal studio sets to casual selfies. Nonetheless, photographs of people of color have historically played on negative stereotypes and fixed identities. In the exhibition Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA, 35 Los Angeles–based artists—primarily artists of color—shake up the field, highlighting their personal narratives, aesthetics, and identities. Curated by jill moniz, the exhibition also includes works by young artists who participated in the Getty Unshuttered program. Getty Unshuttered is an educational photo-sharing platform that teaches photography fundamentals, builds community, and encourages high school students to use the medium as a tool for self-expression and social change. It also offers resources for teachers.

In this episode, guest curator jill moniz discusses the ideas behind the exhibition Photo Flux and looks closely at some of its key works. Getty head of education Keishia Gu then delves into the three-year-old Getty Unshuttered program. Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA is on view at the Getty Center through October 10, 2021.

More to explore:

Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA explore the exhibition

Getty Unshuttered learn about the program

Bokeh Focus learn about the organization

Amplifier learn about the organization

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

JILL MONIZ: Photography, historically, has been used to pin people of color in a particular location to a particular identity or stereotype, and the artist in this exhibition works to unpin that.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with curator jill moniz about the exhibition Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA and then with educator Keishia Gu about Getty’s related photography app, Unshuttered.

Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA is an exhibition of thirty-five Los Angeles-based artists, primarily artists of color, who are transforming photography to express their own aesthetics, identities, and narratives. The exhibition is guest curated by jill moniz.

The works and artists featured in the exhibition are also foundational for young artists participating in the Getty Unshuttered program, which engages teens to work with photography in order to amplify social topics that resonate in their own lives. Unshuttered is a free photo sharing app from the Getty Museum, which also provides lesson plans and digital resources for high school teachers to inspire their students to explore the medium and its social impact. Included in the Photo Flux exhibition is a showcase of photography from Unshuttered participants, works created by young artists advocating for social justice. To learn more about this innovative program, I spoke with Keishia Gu, the Getty Museum’s Head of Education.

But first, my conversation with jill moniz.

Okay, thank you, jill, for joining me on this podcast. Tell us about the origin of the exhibition, its title Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA, and its thesis.

JILL MONIZ: I was looking for a title that could describe literally what I was interested in describing visually, which was photography or photo-based work that has this dynamic energy.

So something that could shake the core of photography, which I believe this work does. For me, photography historically has been used to pin people of color in a particular location, to a particular identity or stereotype. And the artists in this exhibition work to unpin that, to break that down, to refuse it. And to create work, as cultural production, that speaks to the diversity of their stories, their identities, and not as a response to what was happening specifically last summer, because the murder of Black people and Brown people has happened since Europeans first came into contact with these people, from raids on villages to smallpox-infested blankets, but as a way to show that this is a historic act on the part of these artists and others like them; that this work continues because of and in spite of the fact that our lives are devalued and erased in a carceral state.

CUNO: Well maybe the title image will help us feel that and see that. It’s called Support Systems, and it depicts a boxer throwing a mighty left hook into the façade of an office building. What’s the meaning of this image and why did you choose it as the exhibition’s title image?

MONIZ: This piece is by a local artist born and raised in LA, named Todd Gray. And for me, he is a voice in my head when I think about what photography can do. And this image has stuck with me for years.

He was thinking about boxers like gladiators in ancient Rome, and having to engage in these violent matches for freedom. You know, where they fought to the death, and if they could win, then eventually, supposedly, they were free. And he was looking at the way the contemporary society is incredibly racist and denies freedom, even still, to Black people. And so for many young Black men, sports, boxing, basketball, football is a way to sort of gain freedom.

And so this work was born in protest of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. Not for the Olympics themselves, but the way that art and the community, the Black community specifically, was engaged during that time.

And he put these works out on the street around Exposition Park and other places where Olympic events were happening. And I just think that it is a perfect visual narrative of both the battle and the beauty of what our communities face daily; but also the creativity that is born out of that and the fact that we are able to overcome, and not to be mired in struggle all the time, but to be engaged in a kind of life journey that we can win, even when we can’t be free.

CUNO: What is the building?

MONIZ: It’s actually downtown Los Angeles. It’s City National Plaza. But it was called the ARCO Towers at the time when Todd photographed it.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, you’ve presented a number of paired photographs in the exhibition. For example, Laura Aguilar’s Clothed/Unclothed #34, of 1994. Describe the photographs for us and tell us what the pairing of these images do.

MONIZ: I included this set, one, because I love Laura’s work. And her death was a huge loss to our communities. But also, the subject of this work is Willie Middlebrook, who was a very well-known photographer in Los Angeles, and was so important, in terms of contributing really powerful, unique imagery about Black life in LA.

And he has since passed. But the urgency with which this show was put together made it impossible for me to get to his archives. And so it was a really beautiful way for me to honor Willie and Laura at the same time. But this image in particular features him clothed with his two sons, one of whom has since passed as well, and then unclothed. And I think what’s interesting about Laura is that she understood identity as a layered experience, as our communities often experience it, you know.

And now in the vernacular, they call that code switching, where you can present a particular identity in one instance, and then change that identity in another, depending on the context. And I think that these works really get at that, long before people were talking about it on NPR or the New York Times.

CUNO: So what is the significance of the Clothed/Unclothed in the title?

MONIZ: So all of the pairings feature artists who are clothed in one image and then naked in another. And I think that that spoke to both the strength and the vulnerability of the subject, and her own sense of identity.

CUNO: Mm-hm. There’s a sense of intimacy between father and children in the pictures. And it comes across so poignantly in the exhibition, this sense of protection that he represents.

MONIZ: Yes. It’s interesting that you should say that because so many of our men are incarcerated. And it is very dangerous to be a black man in America. You can be killed for sitting in a car, for selling a cigarette, for sleeping in your bed, for all sorts of things that I think White people take for granted every day. And especially that sense of fathering and mothering Black men is incredibly difficult to keep your children alive and keep them out of prison and keep them out of harms’ way in a police state.

And Willie was a beautiful man and a loving father. And I think a lot of the artists that I included in this work, I have personal relationships with because they are such amazing artists and parents, and committed to their children and communities, in ways that I am as well.

CUNO: What about Carrie Mae Weems’ 2003 photographs from May Days Long Forgotten, May Flowers and After Manet? Did Carrie Mae purposely pair these photographs, or are they two taken from a larger set of photographs?

MONIZ: They’re two from a series. I think it’s a nine-part series that she did. But I was interested, one, in these two because they were in Getty’s collection. And as I was building the show and looking at artists that were unknown to the Getty, but also those who had made it into the Getty’s collection, Carrie Mae is the sort of pinnacle of that for our community.

She’s lived in California. Not necessary in Los Angeles, but her work here has been instrumental for the communities of color that engage with photography and photo-based work. And so it was really important for me to honor the fact that she was in the collection and that these works, I think, really depict something that’s emblematic of what all of this work is getting at. That there are the sense of portraiture or photography as a tradition, and then how that tradition can be broken down and broken apart through just changing the subjects in these works.

CUNO: Well, describe them for us, if you could.

MONIZ: Yes. So she was looking at, I think, the conventions of nineteenth century portraiture that were often made in these circular, oval forms. And of course, that portraiture was of white families and people in positions of leisure.

And so she’s getting at, I think, by photographing young girls in particular, in these poses of leisure, ideas about identity and labor, and what it means to see young girls as girls, in the same kind of way that we see young white girls. Because, of course, in the nineteenth century, these girls would have been slaves or they would have been servants to households where they had no leisure.

And so she is both sort of breaking apart this concept of what it means to be worthy of a portrait, but also what it means to be human in this world and seek pleasure and joy and comfort and friendship and a sense of safety.

CUNO: There’s a sense of intimacy too, it seems, and an engagement between the sitters—and particularly the oldest child—looking out at us, and the contrast between the beautiful skin tone and the cotton dress garments that they’re wearing.

MONIZ: And you know, the sense of not challenging the viewer, but just demanding an understanding that she is here.

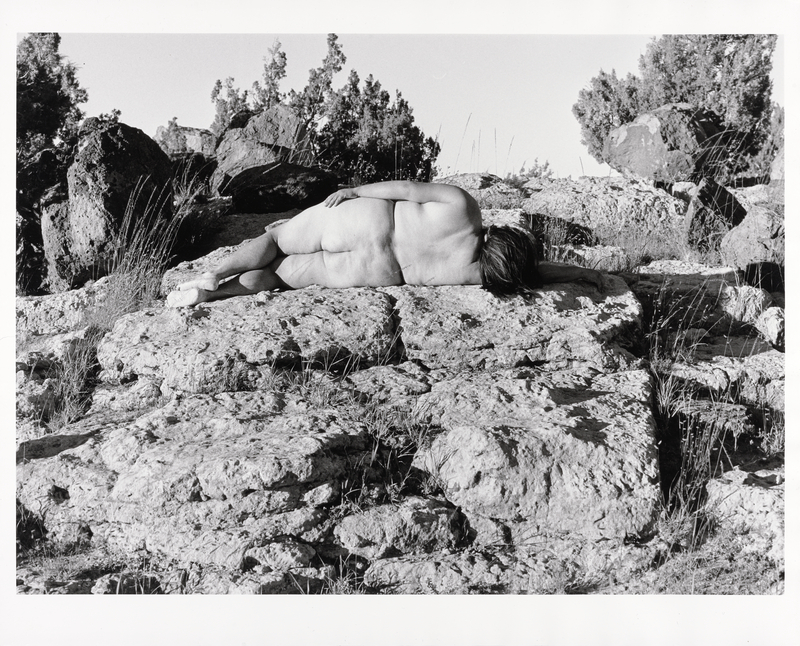

CUNO: And just as they set out a certain physicality among the three sitters in the photographs, Laura Aguilar emphasizes that too, in Nature Self-Portrait #1, from 1996, which shows her naked body lying on a coarse rocky landscape, the body and the landscape kind of echoing each other.

MONIZ: I love these works so much. She was a visionary in so many ways. And they get at this notion of otherness, this position of the other, of non-white people, of subaltern communities as othered, that lie outside of the built environment. And you know, we are historically categorized as wild or savage or sort of more natural than civilized.

But also, there’s this very interesting use by power structures of that identity as being unnatural, and particularly for Laura, who was obese, that there is something unnatural in her body image. And so for her to place herself back in this context of the natural environment and think about her body with a stone, as a stone, as part of the wild, really liberates her from these categories that were placed on her.

And reclaiming, in a kind of fugitive way, the power of what it means to be one with the environment, unlike the built environment in the social sphere, where white people are at the top of that hierarchy and yet so disconnected that they don’t even see the destruction of the natural world that’s happening, as they consume and spread their capitalism around the world.

CUNO: The issue of self-portraiture resonates in the exhibition in a number of different examples. One of them is with April Banks’ Untitled from Déjà vu and Other Histrionics, which itself is paired with another picture by April Banks. Describe these paired photographs for us.

MONIZ: So I chose four sets of diptychs from a larger body of work that April made when she was in residency in Senegal. And the work really describes the layering of history and identity. The photographs are of Goree Island and other slave ports along the west coast of Africa. And what she did, actually, is she took historic postcards of Africans, mostly by French photographers, and she extracted the subjects, the Black people from them, and then she layered them on top of photographs she took in these preserved places, slave castles in particular.

And she was questioning what it means that Goree and these other sites are UNESCO World Heritage sites, and yet the living culture of these places is diminished and nearly erased; and how it is that Africans, particularly in these places, how they can construct an identity that is sort of muted by history, but also layered by acts of survival and knowing; and how it is then that we, being part of the diaspora, see ourselves in relationship to those spaces and those people.

And so they’re incredibly powerful. She makes a space in between the diptych so that it’s very clear that they’re two separate conversations happening, and asking you to find your way into both the contemporary moment and the historical moment of the work. And she does this in ways that I think are really provocative, but also accessible for people who don’t necessarily understand the history of Goree Island or slave castles, slave ports.

What it means to have gone through the door of no return and never seeing your home, your family, your land again; and what it means to form new identities. And so she makes space, literally, in the work for people to be in conversation and build some visual literacy around these images for themselves.

CUNO: Yeah, clearly, the separation between the one figure and the other resonates with the subject matter of separation.

MONIZ: Yeah. And that, you know, that’s the idea of having kind of that fracture or break. And what gets put in it, what we imagine in that little thin line is where we make our identities and where we find ourselves to be whole. And I think this group of four is some of the most powerful work in the show. And I think it’s important that she is seen and these stories and narratives and visual language are understood at the highest echelons of the art world. So it’s a pleasure for me to learn that the Getty has acquired these images.

CUNO: Tell us about Monica Newman’s 2019 photograph Serious, a powerful picture of the face of a Black man seen in profile.

MONIZ: Monica’s Dutch. There are other foreign-born artists in this show, but she is the only technically white or European person, artist, maker that I included. And what’s so interesting about Monica is that her father was born in Indonesia and then grew up in the camps during the Indonesian civil war.

And when he arrived in the Netherlands as a teenager, he was a complete outsider. And she herself is an outsider, both in terms of her relationship to the Netherlands and her relationship to Western sense of public space and capitalism and the structures of power. And so she has historically, throughout her entire practice, sought out communities that refuse and reject those systems.

And she builds community with them on the margins of society, be they living out in the desert or as the unhoused on the streets of Los Angeles, as this particular person was. But she sees them, and I think they really see her as occupying the same space, and they are interested in collaborating with her. And I think that’s the way she describes her work, is a collaboration between herself and her subjects, to make these really powerful and vulnerable and really open images.

And so she often photographs the same people over and over. She goes and spends time with them in their tents or wherever it is that they find themselves on the periphery. And she’s very much interested in not only doing this collaborative work with them, but building relationships. And in this way, her work as a photographer— And the final product is almost secondary to the sort of— I don’t wanna call it social practice, but the literal act of engagement that she does, that for her, is the only place where she feels at home.

And this picture, I love because he’s just an incredibly beautiful Black man who is open to her in their collaboration. And I want people to understand that that’s a possibility; that just because you occupy different spaces or, you know, different ethnicities, that you can have these very authentic exchanges with people. So there is hope for us as a species, that we’ll stop killing each other and we can actually learn to cohabitate and support one another.

CUNO: Well, what does the image of Black masculinity in Duane Paul’s 2018 Jamaica Wedding, One Love #4 mean?

MONIZ: It means that there are so many layers of identity. And Duane is interested in challenging who gets to claim and who gets to name what someone is. He is Jamaican and grew up between Jamaica and New York, and came to Los Angeles a number of years ago.

And I think for him, and for me in my relationship with him, he is masculine. He is powerful. He’s a Black man. And he also is gay and he also is an artist, and he is so many things at one time. And the reason that this work was important to include is that it really describes that we are not singular, that we are not a monolith; that we are layered, sort of like April’s work, and we have histories that are unique and funny and interesting, and we can be playful. We seek pleasure and we seek love and we are love. And I think that you can be a man and be all of those things.

CUNO: There are others in, pictures in the exhibition, in which you explore gender and ethnicity. I’m thinking of the picture of the two Chinese women, The Nymph of the Luo River, Spring, by the photographer Mei Xian Qiu. Describe that for us and what you intended by including that in the exhibition.

MONIZ: Mei’s work is really about challenging context and category, as all the other artists are. But she looks very specifically at her own cultural heritage as a Chinese woman. She too was from Indonesia and expelled. And what it is to both be wanted and unwanted.

Wanted in terms of personal relationships and intimacy, unwanted in terms of nationhood and a larger cultural identity. And she’s interested in challenging, I think, also Chinese ideas about gender. And so a lot of her work focuses on sort of uncoupling traditional roles in Chinese culture from the men and women who actually live different lives.

And so I’m interested in her work because of the beauty of it and the way she uses color and the way that she makes her subjects seem almost 3-D; but also in what she’s trying to do by refusing and challenging traditional and sometimes limiting roles for women and for men.

CUNO: Yeah, that’s interesting. And why don’t you explain the context of the photograph, the setting that it depicts. It looks almost as if it’s a calendar photograph.

MONIZ: They’re in a landscape. Two women embrace in a landscape. It’s a photograph on Plexiglas. And the landscape has been altered and the colors are very pop colors. There’s a lot of pinks and colors that may represent femininity. And they have gorgeous flowers in their hair and in traditional dress, and yet they’re embracing in a very open and public way that’s completely an antithesis of what traditional culture would dictate.

And so she’s challenging the ideas of roles and responsibilities and gender in her community by making the couple a lesbian or queer couple, as opposed to a traditional man and woman. And there is one woman in the embrace that’s looking directly at the camera, like many of the works in the show, and saying, “I’m here. We are here.” And it’s a challenge, and it’s also an invitation to join into this othered narrative.

And that’s why I like her work so much. And all of her subjects have that sort of invitation in the work that asks people to step in and to build a relationship with the material and with the story, and build a visual literacy that extends their own understanding of themselves and of cultures that may lie outside of what they know.

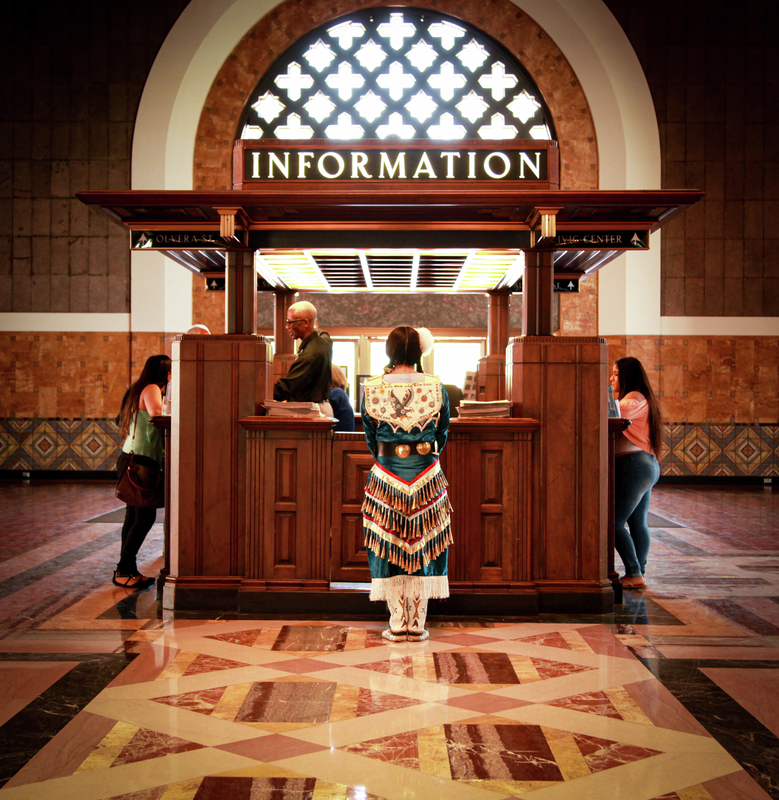

CUNO: What about Pamela Peters’ Viki Eagle at Union Station?

MONIZ: This is an image of an Indigenous woman at Union Station in downtown Los Angeles. And the work is about, again, another kind of challenge. But this time, she faces away from the viewer.

And this work is about mobility, and particularly Indigenous mobility, as a challenge to the way that Americans often fix Indigenous communities in history. Pamela wanted to show that Indigenous people move, they migrate. And like Blacks from Texas and Louisiana, who came to California at the turn of the century and throughout the early twentieth century, many Indigenous communities and Indigenous Americans migrate to California looking for work, looking for cultural community, and looking for a sense of freedom.

CUNO: There’s another work called Indians of All Tribes, which is quite different, in the sense that it’s a parade of figures holding their signs of rejection of the system and the embrace of power.

MONIZ: That’s George Rodriguez and his untitled documentation of the march for Chicano power in the moratorium where Ruben Salazar was killed. And I love this photograph.

Unlike a lot of the other artists in the exhibition, he has worked in a professional capacity, photographing all kinds of events for a very long time. And I think that the way that he bears witness to what has happened in his life and in the lives of other people in his community, not as an accident, but just as this very sort of— I hate to use the word objective way, but unlike, I think, a lot of the other artists, he really is almost a journalistic photographer in this particular photograph, in capturing this moment of power and community cohesion and demand for freedom.

Because these works are quite small, there is something very intimate about the way that he captured this particular moment. I wanted people to have to lean in and look and see the faces of those people who were coming together to demand change. And I think because we see so much of the protests on the streets, particularly after George Floyd, that I wanted people to think more along the terms of intimacy and individuality in the collective, and what it means to risk your life for what should be your right in this country.

CUNO: There’s the poignant untitled picture of Japanese girls playing ball outdoors at Manzanar, one of the camps that the US government incarcerated more than 110,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens during World War II. It’s a poignant way to sort of bring the exhibition to a close, the sense that this history is a long, shared history.

MONIZ: This is a Toyo Miyatake image. He smuggled his camera into the camps and documented his life there. And it is, I think, poignant that we have a sense of what it means to be a community that is walled off, that is viewed with suspicion, that is judged by stereotype. And yet they thrive. He thrived.

He captures young women playing basketball, I think they’re playing, or volleyball, and they’re very engaged in the play. And it looks as if they’ve almost forgotten where they are, because they are so deeply in the game. I guess basically I chose this image to show that we can’t be contained.

CUNO: What about the Christina Fernandez photograph in a laundromat?

MONIZ: So in this particular series, the Lavanderia series by Christina Fernandez, she documents a laundromat, a public laundromat. And I chose #8 because it is a photograph of a laundromat, always looking through the windows, but it’s empty, for the most part, with only a couple of people inside. And this is a very joyful image for me, having spent many days at laundromats.

For a lot of Black and Brown communities, who don’t have washer and driers, or in my case, needing to wash blankets all the time, having a bunch of children, messy boys, that I would go to the laundromat. And where you see whole families, often, doing the wash on Sundays or the weekends. Or individuals just in quiet contemplation, as they do their laundry. And that these are really communal spaces that are important in our communities. As sites of gathering, but also as sites of rest and repose. It was a way for me personally to get some space and to have some quiet time as I did laundry.

But there is a sense, I think, in these works, which is why I chose it, that the ideas about life in California in particular, but life in America in general, and mobility and wealth and privilege are always imposing on our communities. And yet we find ways to do really simple everyday tasks in a way where it is by the very nature of a lack of access to that kind of mobility and elitism that we can gather in these spaces that are so vital in our communities. And actually, they become places of great pleasure. And I just wanted to show that in her work.

But it’s also a really powerful image for people who recognize it as a space for joy and for labor.

CUNO: Yeah. How does all this fit into the title of the exhibition, Photo Flux: Unshuttering Los Angeles or Unshuttering LA?

MONIZ: Unshuttering LA came from my relationship with the teen program, the Getty teen program, LA Unshuttered. And I include in the exhibition a wall-mounted flatscreen where we have images from teenagers around the country who submitted work to the Unshuttered app and platform.

And it also is sort of a double meaning. So it ties into the Unshuttered program, where we ask teenagers to really use photography to understand their world and build visual language and visual literacy that can be used in service of themselves and others.

But it also describes the way that these photographers in this exhibition have revolutionized photography in a really radical way, some of them no longer using traditional photography, but having very strong photo-based practices that extend and evolve and radicalize the medium.

CUNO: Well, thank you, jill. This is a powerful, beautiful, and poignant exhibition, and we certainly are pleased and honored to be having it presented at the gallery at the Getty as we reopen to the public, after more than a year of being locked down during COVID-19, and as we acknowledge the radical reckoning following the murder of George Floyd and so many other Black men and women. So we thank you again very much.

MONIZ: Thanks for having me.

[musical interlude]

CUNO: Well, thank you for joining me on this podcast, Keishia. And tell us about the origins and purpose of Getty Unshuttered.

KEISHIA GU: Right, well, thank you for having me, and I’m excited to talk about Unshuttered. So Getty Unshuttered is actually—it’s a partnership that is between the Getty and the Genesis Inspiration Foundation. And it was started in 2018.

So Genesis Motor America was starting their corporate social responsibility arm of the company. They wanted to support arts education, they wanted to inspire creativity in children, and the Getty was a really strong launch partner for that work.

But it’s built on a simple concept. Unshuttered is the belief that art can radically change social directions, policy; that it can touch the mind, the head, the heart; and that we can transform and we can connect ideas and to one another. So it’s not a classroom; it’s a launchpad. It’s for young people; it’s to fuel their creative growth, give them direct access to artists, mentors, curators, gallery and exhibition spaces. So anybody can pick up a camera, anybody can pick up their camera phone, show their view of the world, and that’s what we think Unshuttered should be.

CUNO: Now, you’ve probably answered my next question, but why did you choose photography?

GU: Photography seemed like an accessible entryway into the art world. It’s very common for students to have access to cameras, to have access to technology that, you know, includes cameras on their phones. It’s very quick for kids to be able to upload, download, share.

And so it just made sense to build an Unshuttered program around photography, and to build it around the idea of photo sharing for young people, because that’s what they seem like the young people love to do.

CUNO: Tell us about the photo sharing. What does that comprise?

GU: So Unshuttered has an app that’s available on Android and it’s available on Apple. And so what the app allows you to do is it’s a positive community for sharing. It’s to share your passion for photography. Not just the picture itself, but really the skills, the messaging, and the narrative. It invites you to be a part of this community.

It allows you to pick up quick photography skills. It has a breakdown in terms of, do you wanna look at photos that are related to color, composition, to lighting, to movement, perspective? It allows kids to be able to vote, to have skill challenges. So there’s a lot of mechanisms in it that, make it really interesting and, like, friendly competition, I would say, in terms of what they can do on that Unshuttered app.

CUNO: How many students have participated in the program?

GU: So to date—here’s some interesting numbers—pre-pandemic, we had two iterations of Unshuttered. And that had about thirty-five students that did an onsite digital photography intensive at the Getty. They work with teaching artists, they worked with curators. And from those experiences, we were able to create live events. We were able to create showcases and actually, exhibition space within the Getty.

This year, because of the closures—we had wanted to take Unshuttered nationally anyway, and so we partnered with a few organizations. And with one of the organizations we worked with, we had an open call, a national open call for photography submission. That received over 1,500 students from around the country that participated in Unshuttered this year.

CUNO: Wow. That’s great. Now, this year the program’s theme is “In Pursuit of ___.” Like, tell us about that.

GU: Yeah, so the theme for the third year was exactly that. It was “In Pursuit of ___,” and it was inspired by the Declaration of Independence. Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. What we wanted students to do is to fill in that blank for themselves. We were a country that was grappling with isolation, concepts of freedom, concepts of justice.

We wanted young folks to look into their own world and figure out what that phrase meant for them. It seemed very timely. We were on the precipice of a major presidential election. In the pandemic, it seemed to have even more broader and inclusive tenure. And so we have some very interesting responses, in terms of—what is it that the current generation wants to see for the next generation? What are they in pursuit of that’s gonna propel that change in the world that they wanna see?

CUNO: How did you have these conversations with the students, who were virtual to you?

GU: Yeah. The conversations with the students happened a couple of ways. They, you know, were able to get access to very prominent artists. We were hosting workshops for students, in terms of how they could participate. We were hosting workshops for teachers. It was based on the theme, but it was also based on, just fundamental skills of photography.

One of our great partners that we work with in Atlanta, an organization called Bokeh Focus, actually works with students that are adjacent to the juvenile justice system. And so there were very strong conversations about justice, freedom, the system itself. What is in the images that the kids want? What are the messages that they want to say? You know, it was a pandemic. It was very trying. But the photography is what made it cathartic for the young folks.

You can really see the vulnerability of young people who have parents and who have had family members impacted by the system, who have faced incarceration themselves. There’s an incredible photo that is, sadly, one of my favorites from the series, but it’s a haunting photo that a nineteen-year-old took. And it’s a mother standing in the streets of Atlanta during the social uprising after George Floyd was murdered.

And the mother is standing with her two black sons and they’re draped around her waist. And she has a sign up that says, “Her son today. Is it mine tomorrow?” And the fact that a teenager took that photo and then had deep statements about what it means for them to be a young black person in Atlanta, and to express a sentiment of being tired, of being tired of not being able to live without persecution, but creating art that reflects, the change that they wanna see, and the passion that they have for becoming someone that can make a difference. That to be one of the most powerful moments of Unshuttered, to really see how kids took on what was happening in our country.

CUNO: Did it surprise you how sensitive students could be?

GU: It does and it doesn’t. I mean, I’ve been a classroom teacher for almost all my life, and a counselor, and I have seen kids be resilient. I think that this is the toughest year that young people have ever— In my experience as an educator, this is the toughest year that I’ve seen high school students have to move through and navigate this world. To see their photos of isolation, to see their photos of justice, to see their photos of wanting clean drinking water, better environment, immigration reform, safer schools, gun laws passed.

They’re just so aware. And I think that’s what surprised me is that, you know, I just don’t remember, as a young person, being as aware and as deeply reflective and as deeply motivated as some of these young people who participate in Unshuttered, as much as they show through their photography. So it’s— I love the program for that. It gives me goosebumps.

CUNO: How successful was the project when you dealt with national partnerships in this edition, given that it was an adjustment that everyone had to make?

GU: The national partnerships, they couldn’t have come at a better time, because when we weren’t able to have the the work onsite, it really did lead into the work that was happening with Amplifier! and with Bokeh Focus. So with Amplifier!, we wanted to learn from them.

We knew that they immediately, they already were a design lab. They amplify important social movements, and they do incredible iconic campaigns that are focused on social justice and grassroots-organized. So for them, it was easy for them to host this open call, to lean on their founder, to lean on their CEO to, you know, help reach out to the young people.

They were able to help us with projections. It was something that—we had tried onsite, but we had not tried in terms of the scope of what Amplifier! is used to doing, where they go into big spaces and they take over buildings. So it was incredible to see the work of the young artists that participated, the winning artists that were chosen by Amplifier! judges and by Getty judges, that were projected in public spaces—of course, here in Los Angeles; in Seattle, in their international district; New York City, the iconic Brooklyn Bridge in the background, the Statue of Liberty, Times Square. They just had a digital projection truck sitting in the midst of Times Square. Washington, D.C., with the Capitol in the backdrop; Anchorage, Alaska, amidst all the beautiful snow. So that was exceptional work.

And then with Bokeh Focus in Atlanta, their ability to reach a population that was new to us and for us to do it with an incredible amount of humility, an incredible amount of care, to learn about students that are adjacent to the incarceration system, to hear young people from Atlanta be able to express their frustration, to be able to express what they would like to see happen on a systematic level. I would say that was incredibly successful because the Getty, we learned so much in our team, and we were able to share Unshuttered and photography, with such a broader audience.

CUNO: How would someone gain access to the amplification of Amplifier!? That is, the results of their work with you. How would we gain access to that?

GU: We have all of the submissions from the students. And so the Getty currently, our teams are working on having a virtual exhibition in about mid-summer, about July. So you’ll be able to see the culmination of all of that work. But at the same time, our partner organizations have, of course, noted their partnership with the Getty.

So amplifier.org has their “In Pursuit of ___” campaign up with all of the winning artworks. So with images from the projections that happened around the nation. And Bokeh Focus has two of their exhibitions up on their website, bokehfocus.org. And they did an exhibition in the fall that was around isolation; and they did another exhibition in the spring for us, which was The Pursuit of Justice.

CUNO: What about your partnership with teachers? Tell us about the Getty Unshuttered educator portal, how it works.

GU: The educator portal was launched in June of 2020. And so we know that Getty Unshuttered is a pathway for young people, for aspiring photographers, but we wanted to be able to provide teachers with the tools that they could use to formalize Unshuttered in the classroom, that they could use against standard spaced approach to curriculum.

So we put together this portal between education and our interpretive content team. We worked with outside teachers, with many people within Getty design and communications, to come up with these lesson plans and resources. The best thing about the lesson plans is that it’s actually inspired by photography from the Unshuttered students. So the students get to see their work used in even more exciting ways, beyond just being exhibited or being on the app.

That we actually pulled their work, so that teachers can learn from the photography that they took. We used the Getty collection. So the inaugural series of these lesson plans focused on the intersectionality of social justice, of advocacy in photography and how you could use that in the classroom. We have a series of lesson plans on digital narrative and storytelling. And then we have a set that will be released this summer that’s just about the fundamentals of photography. So teachers, by the end of the summer, will have close to twenty lesson plans available to download for their use from unshuttered.org.

CUNO: And are these teachers just national, or are they also international?

GU: The teachers are international, as well. We have seen a lot of downloads and hits, you know, coming from Korea and Ireland and Spain and Mexico.

CUNO: How does the relationship between Unshuttered and Photo Flux, how did that happen and what are the results of it?

GU: I think that first of all, Photo Flux is an amazing project and an amazing exhibition. And when we closed, we knew that we were not going to be able to get a round of Unshuttered work up fast enough, that was happening at the same time as, you know, the social unrest that was happening around the country.

And so it was a quick pivot to leverage the good backdrop and the foundation of Unshuttered that reaches out to diverse audiences; that reaches young people who are change makers; and to give them a sense of aspiration with Photo Flux, to say, these are practicing, talented, skilled, celebrated artists that are right here in the Los Angeles community, that oftentimes don’t have their work celebrated in a museum in this way.

And so it was a perfect culmination to say these are celebrated artists, we have emerging artists through Unshuttered, and to put and juxtapose those images together? It was needed, it was timely, and now the next iteration of Unshuttered will come from this inspiration of Photo Flux, so it’s been an incredible project.

CUNO: Now, I gather that the apps have generated something more than 23 million impressions since their launch. But what’s the future of it?

GU: The future of it, certainly, what we would like to see is possibly a little bit more hands-on approach from the young people that are actually using the app. We have great ideas about Unshuttered 4.0, what we would like to see in the fourth year, about how we can reengage with our local community and with teens around the county, because we haven’t had a chance to work face-to-face with them in this last year.

We would like to have young people that are helping us promote Unshuttered, that are taking this app or taking this work back into their classrooms and being partners and thought partners with us, in terms of generating content, helping to evangelize the program, and just being ambassadors. So that’s what we would love to see. It’s been really controlled a lot by the adults, but I always feel that you can’t talk about teens without involving teens. So we’re looking for some great ambassadors out there to help us.

CUNO: You had something you call gamification. How does the gamification work?

GU: So the gamification of it is—it’s common in game design. It’s basically, it’s a skill tree. It allows you to divide masteries in skillsets and in discrete tiered sets. So what you can do with Unshuttered is actually go in and start with, I wanna work on lighting. And you continue to advance in that skillset and you can move on to another skillset like composition.

And so it adds that fun, light element to it, where you’re submitting photography, you’re having fun, you’re becoming an expert. And that’s something that, you know, game designers certainly love to see, is that you’re able to keep people and audiences engaged. It gives them a sense of personal achievement. And then at the same time, they’re sharing with other teens, so it gives them a broader sense of community, to say, “Look what I did. Look what achievement I’ve mastered.”

CUNO: Is Unshuttered an annual event?

GU: Unshuttered has been an annual event. So we keep it going. So we’ve had our class of 2018, 2019. In 2020, it’s a longer runway. So 2020 went into 2021 because of the closure. So that is ending now, this third year. And then the fourth year of Unshuttered will start again in the early fall of 2021.

CUNO: Well, it’s a fantastic project, Keishia. So thank you for all your good work on advancing it. And thank you for another successful Unshuttered year.

GU: Thank you. Thank you for your support and for helping us to grow this program. Because of the Getty Trust and the board and our leadership’s interest, we have been able to take this program to heights that I could never have imagined. So thank you so much.

CUNO: Photo Flux: Unshuttering LA is on view at the Getty Center through October 10, 2021.

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

JILL MONIZ: Photography, historically, has been used to pin people of color in a particular locatio...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.