Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“It was really powerful to be on the road following her footsteps. It just gave me an incredibly profound respect for her grit.”

In the 1930s and ‘40s, photographer Dorothea Lange drove up and down California and across the American West, recording people and their living conditions with her camera and notepad. Eighty years later, poet Tess Taylor saw echoes of Lange’s photographs of temporary housing, migrant labor, and precarious livelihoods in contemporary California. Taylor retraced Lange’s steps, following itineraries from her notebooks. Taylor’s book-length poem Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange explores Lange’s legacy in California, combining her notes and photographs with Taylor’s lyric poetry and oral histories. The result is a poignant exploration of the social and environmental challenges facing California today.

In this episode, Tess Taylor and Getty photographs curator Mazie Harris discuss Dorothea Lange’s career, iconic images, and continuing impact. Taylor also reads excerpts from Last West.

More to explore:

Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange buy the book

Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures buy the book

Tess Taylor

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

TESS TAYLOR: It was really powerful to be on the road following her footsteps. It just gave me an incredibly profound respect for her grit.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with poet Tess Taylor and Getty curator Mazie Harris about the photographer Dorothea Lange.

In 1936, Dorothea Lange photographed Florence Owens Thompson and two of her children in a temporary camp in Nipomo, California. Eighty three years later, poet Tess Taylor wrote the poem, “Nipomo, Sunday, 2019,” which begins, “You’re looking for the woman who shot the photo./Yes. We know about her. My parents talk about her./People come still, looking for her./Like you they want to know about her….” We all do—Lange’s ability to capture the woman’s rugged features, her young children wrapped around her neck and shoulders, the dignity of labor. It’s a commanding picture, still.

Tess Taylor’s book of poems, Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s 2020 exhibition, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures. I recently spoke with Taylor, and Getty photography curator Mazie Harris about Dorothea Lange, her work for the Farm Security Administration, and her contemporary appeal and relevance in our time of migrant laborers and visible poverty.

I’m pleased to be speaking with Getty assistant curator of photography, Mazie Harris, and poet Tess Taylor, about the work of the great twentieth century photographer Dorothea Lange, and Tess’s poetic response to it. Thank you both for speaking with me this morning on this podcast.

Now Mazie, give us a sense of Dorothea Lange’s career as a photographer, and especially during the 1930s.

MAZIE HARRIS: She was born in New Jersey in 1895, so right around the turn of the century, to second generation German immigrants, and was raised, for the most part, by a single mother. By her late teens, she’d already apprenticed with portrait photographers in Manhattan, and in her early twenties, she moved to San Francisco and opened a photography studio of her own.

At that time, she was making fairly typical family pictures, portraits that were flattering, that utilized retouching. And in that time, she was also developing some skills that would continue to serve her later on. She was learning patience and how to make people comfortable in front of the camera, to solicit a kind of a natural attitude, not that sort of posturing we all so often bring when we have our images made.

But in the 1930s, her life and her work really shifted radically. It was, of course, a very transformative time for the country more generally. And Lange was married to an artist, so they were both impacted really deeply, as were most Americans, by devastation of the Depression. Her husband, who was a painter, Maynard Dixon, was able to work for what was a precursor of the Works Project Administration. So that’s one of those important programs by which the government supported artists who were kind of contributing to civic life.

But their marriage was beginning to unravel, the country was beginning to unravel, and she felt she couldn’t ignore the really just staggering levels of unemployment all around her—the suffering, the poverty. So she began to photograph outside her studio. She made images of people lined up for food, of labor rallies, [an] iconic image of a policeman standing before a group of people who are protesting the conditions of the time. So these are images that continue to resonate with us today, images of American hardship.

She was a mother of two young children, and so for a while, she continued her portrait photography to help finance this new way of working for her, these documentary images that she was making. And a social scientist, an economics professor, Paul Taylor, began to use her images to accompany articles that he was writing on poverty, on migration. They started working closely together, and were ultimately married. And they begin to focus their attention, really focus all of their energy, on the plight of Americans who were impacted by the Depression.

This a time of horrible droughts and dust storms in the plains, and so Americans were moving in droves to California, to try to work in the fields. And the conditions that they were living in were completely unsustainable. Families were living in totally makeshift ways, with blankets and tarps kind of strung up for protection. They didn’t have proper shelter or sufficient food or sanitation. So the reports that Lange and Taylor begin to produce together, they were meant to help Americans, to help politicians to see the struggles of their country, and to try to encourage action.

CUNO: So how common was it to be a woman photographer in the 1930s?

HARRIS: It was unheard of to have a photographer at all on the sorts of government reports that Paul Taylor was producing. So when Lange was brought on, it was originally as a sort of clerk or stenographer. That was the way that they were able to have a budget line for the work that she was doing; they called her film a clerical supply. But it soon became clear that the photographs could help in kind of swaying hearts and minds. So photography became a bigger part of government programs, to document the conditions of the country, and so other women began working in that way, as well.

It was really in the 1880s that technological developments made photography more accessible to wider numbers of people. So women and people from different economic backgrounds could begin to make photographs with the advent of the Kodak in the late 1880s.

Lange was a contemporary of photographers like Imogen Cunningham and Margaret Bourke White. It was really a time when economic instability and political extremism sort of enabled opportunities for women. So you had women making studio portraiture, like Lange had, and women working as photojournalists, like Bourke White did.

CUNO: Now, Lange contracted polio at age seven, which left her with a weakened right leg and permanent limp. Some have suggested that this might’ve affected her photography, making her approach her subjects slowly. Did she ever speak of her polio?

HARRIS Late in life, she said that the experience, the physical pain, being teased by other children, the shame her mother felt about her condition, was humiliating; but that it also really formed her. It guided her, and ultimately, it helped her. She felt people were perhaps more kind when she approached, and she was certainly made attuned to suffering. The experience made her very empathetic. She didn’t just look at the world, but she really listened to the people she photographed. And their words, the cadence of their speech, the rhythm of their way of talking was really important to her way of working.

00:25:32:11 CUNO: When did you first come across her work?

HARRIS: I don’t remember the when, but I definitely remember the power of it for me. I grew up in the plains of Texas, and it was such a jolt to see work, a photographer showing these small towns that I knew so well. I was really moved by these Depression era photographers who were able to capture the beauty of the region. It’s a stark beauty, but it’s a beauty of the prairie. And they’re able to feel the hardship of the landscape, but also the strength of rural life. I was really moved to see photographers who had respect for those people who struggle with economic hardship.

CUNO: And Tess, when did you come across Lange’s work?

TAYLOR: I’m like Mazie, you know? I don’t remember not knowing it. And I remember it, the story of it somehow weaving in as a backbone, that this was something that an artist did to come and help people and rescue us and make us visible.

And I grew up in Berkeley, and there was a sense that she was around as a ghost, as a kind of artistic grandmother to us. My high school, Berkeley High School, has a WPA theater that gathers people. There’s a WPA post office. And she was a kind of a point of entry into noticing all of this work that had been done to gather and fortify us in a time of crisis. And that came back to me very strongly because arguably, we’re in a type of crisis right now. You know, there are many crises that we’ve been dealing with—COVID perhaps the most visible, but we have many preexisting conditions before COVID that are— you know, have reached a crisis point.

So she came alive for me when I arrived back from the East Coast to the town that I grew up in, and became a mother and was circling the blocks of my neighborhood, which I had never loved as a child. And I realized, I learned, that she had photographed my town quite a lot in the 1940s. And for me, this was a little question. What could Dorothea Lange have found interesting here?

And I realized that there was like a huge story that she saw in my town, which was partly the act of people settling after the 1930s to work in the shipyards, and the creation of one of the first desegregated workplaces in America, and the kind of hope and promise of getting out of those provisional housing and into something, these small bungalows, and into a middleclass life. That was partly a happy thread in her photographs.

But at the very same moment in 1942, when she was photographing my town, El Cerrito California, she was photographing it as a ground zero for Japanese internment, and people were being forcibly removed from maybe exactly the same homes, or other homes that were being torn down to make space for the homes that she was photographing.

And the sense that she had seen in my town its roots in American paradox, and that she saw that as something that she wanted to document. She has a note to herself in a café around the corner from where I live, and it said, “Photo essay on El Cerrito, 1942.” Now, did she do a photo essay on El Cerrito? I don’t think she did. But the vision that she thought that it was interesting enough to do that really inspired me. And I think that sense that Maize has of having your place seen and documented with wisdom and compassion is really, really meaningful to artists, but also just to people. People really feel wonderful when they feel seen. And it’s that legacy that’s very meaningful with Lange.

CUNO: Tess, you contributed your book-length poem Last West to the Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. In your poem, you include an excerpt of a poem by Archibald MacLeish, Land of the Free. MacLeish described his book not as a book of poems illustrated by photographs, but a book of photographs illustrated by a poem. Describe the book for us and tell us what he meant by that remark.

TESS TAYLOR: Well, MacLeish is this fantastically interesting poet of the 1930s, who is part of the civic movement to kind of have conversations about democracy and what democracy is, and preserving democracy in the face of fascism. And so he is really a poet who engages civic life and collaborates with a lot of artists. And one of his projects is to have this poem called Land of the Free, and to engage a lot of these photographers—Lange and her contemporaries—in this beautiful sort of spread of iconic American pictures.

And also of pictures of an America that’s suffering, you know, and emerging out of a sharecropping economy and towards a wartime economy. Even though maybe they don’t necessarily know exactly that those are the bookends, we can see that experience now. And Land of the Free is a— it’s a little bit of sentimental poem. And it really has to do with wondering whether that American promise is going to hold, especially in the face of the Depression.

And it also sort of talks about the westward migration that’s happening that Lange was witnessing and which she documented, but also, which was a big part of the 1930s getting off these small farms and small agricultural holdings and moving west. Which is one of the migrations that shaped the world that we inherit. And it’s something that we can think about, in a moment when they’re forecasting climate migration at a level we’ve never seen before. Just the cultural change of the 1930s to forties, in terms of the switch in where people lived and how they lived.

So the poem, Land of the Free, has this wonderful mythic quality to it. And because I was writing a little bit about western migration, I quoted him, because he’s got this beautiful little bit of myth. “Get to California, with the sunshine/Shining on the sunshine in the sun/Get to public grass in California/Get to parkways by public fences/Get to roadside camps across the junctions.”

It’s worth noting that he included many photographers. But actually, Lange had something like six photos in it. She was really a very, very big part of the visual landscape of this kind of iconic and mythic America that he was gathering for that poem.

CUNO: Now, MacLeish’s book includes one of Lange’s best-known photographs, Migrant Mother, identified in the book as Pea Pickers in California. Mazie, can you describe the photograph for us?

HARRIS: This is an image that many of us have seen, of a woman in a sort of pieta pose, grasping her children, with her other children around her. And it’s a story that we continue to learn about. Lange was hurrying home to her own family, when she saw a sign that there was a camp and she kept driving. She wanted to get home. She wanted to get home. And then she found herself making a U-turn about twenty miles later, and came back to photograph this woman.

She says, “I was drawn as if by a magnet to this woman.” And living in hardship, they’d moved, as so many had, to try to make a living from the land. And she made the photograph and she sent it off to D.C. And immediately, there was a sense that she’d really gotten at something special. And when the photographs would go off to D.C., they would get published as the editors saw fit. And so the photograph began to sort of have a life of its own.

But Lange and her husband were worried that government wasn’t moving fast enough. And so they actually released some of the images of the Migrant Mother to the local press. And the local press started to really bring attention to the plight of the people living nearby. And so it was a really early instance in which we have the power of these images, of these empathetic images to move the world and to bring about change.

CUNO: Tess, if I’m not mistaken, you don’t use the iconic picture in your book. In many cases, your poem is paired with lesser-known Lange photographs. Tell us about that choice that you made.

TAYLOR: So my book began a different way. I began thinking about Lange and how I inherited her legacy, partly because I grew up in a town that she photographed in the thirties and forties, and partly because the visual landscape of California, as anyone knows, is full of tents and all kinds of provisional housing.

And I was thinking about Lange for both reasons. The way that she made photographs that capture the backstory of the California that we inherit now, and also about the way that the subjects that she photographed felt eerily prescient to the moment that we’re living in. And so I made a project of going to the Oakland Museum and reading Lange’s notebooks. And it was really her notebooks that brought me into this project of poetry, because as well as being a photographer, Lange was a note taker.

And it was partly, I think, that polio that we talked about. She would be getting to people slowly. She’d be asking for some water. She’d be getting them to tell a little bit about who they were and how they’d come to be on the side of the road or in a camp like that. And she would take their pictures; but she also had a very small notebook that she tucked in the pocket of her pants. And she would go back to the car and write down what they’d said, with a pencil.

And so her notes are full of these really fascinating microhistories of place. And it was the notes themselves that really spoke to me as a kind of oral language, an oral history of that time, a chorus of voices that we can still hear, telling stories about their condition in a way that feels really resonant across time. And so though I love photography, that was the part that let the poet in me leap alive.

And so I was so lucky that Sarah Meister, at the Museum of Modern Art, took an interest in the project and wanted to weave it into her exhibition. And as we thought about what I was doing, bridging the past and the present, writing letters to Lange from the present, literally writing her a letter from Nipomo, California, where she took that picture of Migrant Mother, we decided that we wanted to sidestep those iconic images and look at images that sort of sat in a middle distance, that remind us how contemporary Lange feels to the moment.

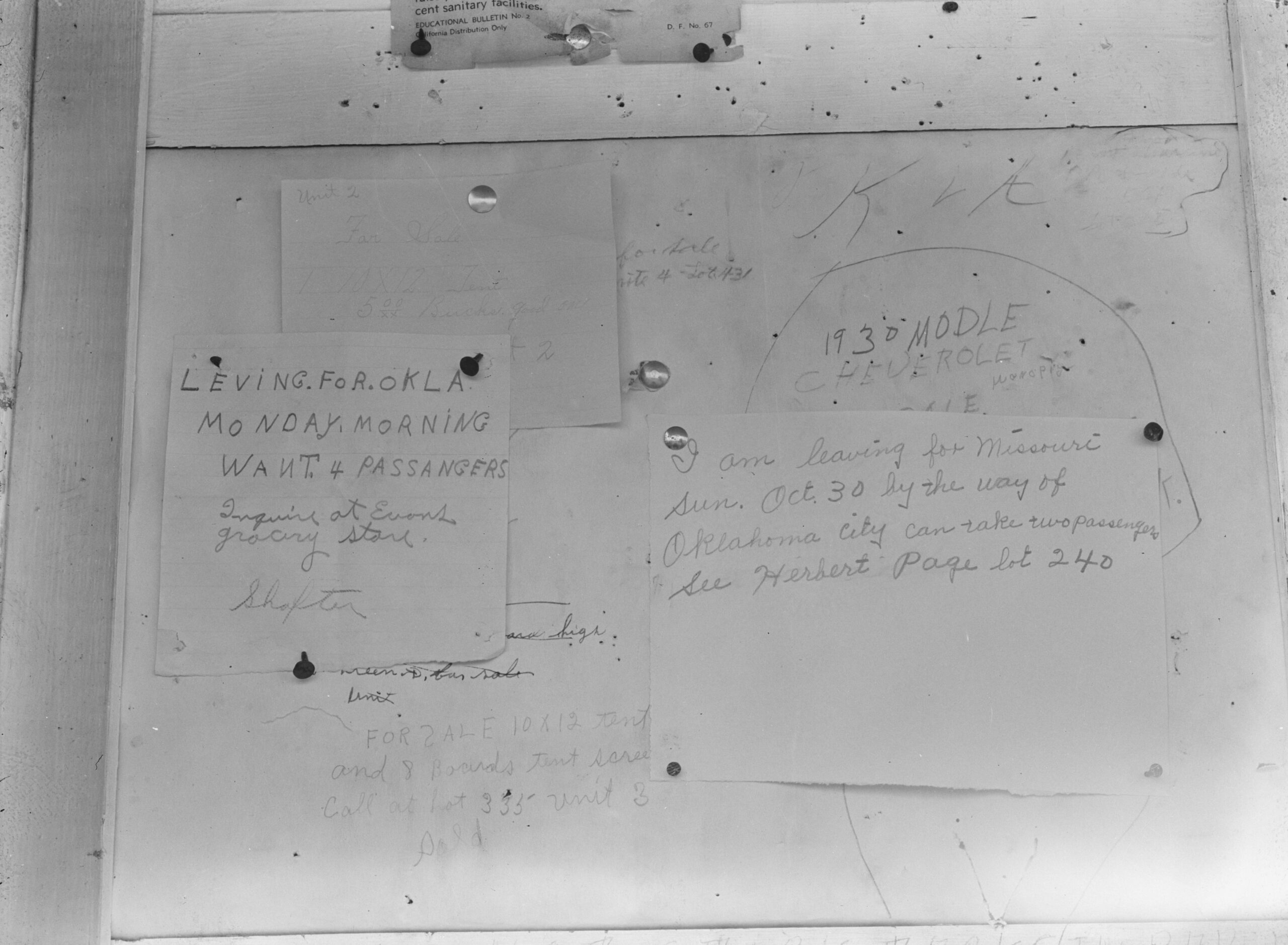

So one of the images that shows up in my book Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange is of a bulletin board at a camp. It’s just papers tacked to a wall saying, “Leaving for Oklahoma. Coming back, driving. Need gas, need help.” And the reason that we picked that picture is that I spent a year visiting an encampment in Berkeley called the Here There Encampment, where people who are not sheltered live together in community.

And it has a bulletin board that looks very much the same. And it’s really about when jambalaya is served at what church; when somebody is going to Target and giving a ride, so people can pick up their prescriptions. And so there’s a sense there of people gathering community resources, even when living in a provisional way, and these temporary but very powerful forms of community that people who are in need can give one another.

And so that image felt contemporary to me, as well as rooted in the 1930s. So for me, my project was also to think, how is Lange a lens that lets us see the present?

CUNO: I’m looking at that photograph that you just described, of the notes on the wall in camp. And little fragments of people’s lives are indicated there. Is this the photograph as Lange made it, or has this been cropped in the production of your book, or what relationship is it to the original photograph?

TAYLOR: Some of them were cropped. Although Lange herself cropped her photos many different ways, so it’s— You know, we get into this vision of what’s the original and what’s, you know— She had these many, many contact sheets and many versions.

I know, for instance, that this cover shot, which is also salt and pots on a table, sort of a dented tin coffee pot, a kind of a camp kitchen under maybe a burlap shelter, that was a picture that we picked because, again, it feels very resonant to the kind of ways that people assemble provisional shelter.

And Lange was interested in that, all throughout. She really was interested in, like, what is it covers people? What is it that swaddles people? What is it that people use to make the body comfortable? And there’s something very beautiful and bodily, and also haunting, about these artifacts that people surround themselves with, perhaps in very precarious locations.

CUNO: What about the photographer’s travel report that you reproduce in your book?

TAYLOR: Yes. This was something I wanted so much to have. And it’s United States Department of Agriculture Farm Security Administration Photographers Travel Report. And it’s very beautiful in the way that documents from the 1930s are beautiful.

But it’s also this record of Lange working and Lange on the road and how far she’s driving each day, mile after mile. And she’s submitting this, I guess, to get reimbursement for gasoline or as proof of her efforts. And so Berkeley to Chico, Chico to Burns Oregon, Burns to Boise Idaho, Boise to Gardiner Montana, Gardiner to Boseman, Boseman to Billings.

I mean, this is when she is off really trying to expand this work that’s done in California migrant labor camps to a wider American story. And she’s always aware about being at sort of the cusp of something, some wide American story which is unfolding before her eyes. So you know, it’s beautiful as an artifact and beautiful, also, as a testament to incredibly hard work.

CUNO: Yeah, I love the rhythm of the— of the text as you read it. There’s also the documentation of the times that she left, like Berkeley at 11:22, and arrived Chico at 7:30. Leaves Chico the next day at 5:05 and arrives at Burns Oregon at 6:10. You can just— you can track— trace her steps or her passage so intimately.

TAYLOR: And these were not easy drives. I was driving down to Imperial County from Berkeley and visiting both a shelter where they house migrant laborers and homeless people in same place—which I think Lange would’ve found fascinating, because migrant laborers are actually people who have houses elsewhere, but have to come work. And people without shelter, who are homeless, are kind of in a slightly different category. But that shelter sort of lumps them.

And I visited, also, a place where Lange had photographed carrot pickers in the 1930s. And now, really just very close to those same fields, is a migrant detention center that holds 782 people, which kind of is a testament to what is happening to people who are in migration today. So those visions were very resonant. But the drive was hard and long. And like Lange, I had two kids at home. And these were sixteen-hour drives. These were really long ways to get down to these places.

And she was on the road driving so far, and I can’t imagine what it would’ve been like in the thirties, with the roads of the 1930s, with the tires of the cars of the 1930s.

It was really powerful to be on the road following her footsteps. It just gave me an incredibly profound respect for her grit.

CUNO: You call your book, as you mentioned it, Last West: Road Songs for Dorothea Lange. Why “road songs?”

TAYLOR: Well, I mean, it is kind of funny to say that I turned Dorothea Lange’s notes into a poem, because most people think of her as a photographer. And they certainly don’t always think of her as a poet. And yet there was this way in which she has these very gritty details of people’s lives, and then her contact sheets are full of these landscapes of California that just show incredible tenderness for land and for the environment.

You know, she had a very early environmental consciousness in her photos, and also this sort of unintentional lyric that shows up in her notebooks. And you mentioned loving the rhythm of the Photographers Travel Report, but it was the rhythm of her notes that brought me in. “Coachella, Calipatria, Niland, Holtville, Calexico, El Centro, Brawley, back up 99. Edison, Tulare, Turlock, Modesto, Westly, La Loma, Marysville.”

Now, that’s an itinerary, but it’s her list of towns that she’s going to visit in Imperial County. But it’s hard, when you’re a writer and someone with an ear cocked to language, not to just wanna say it out loud. And she also had this beautiful ear for an American vernacular. “How you gonna get by on just two bucks a day? You can’t find any decent place, unless you pay good money. What difference what country, what state, what agency? What does it mean to photograph home?”

And really telling lines like, “This country’s a hard country. When you die, you’re dead. That’s all.”

CUNO: And why do you think that her work opens up so well to poetry?

TAYLOR: Well, I think it’s that music that in the records, the staccato phrasing, the lists that feel so fascinating, these notes that she has to herself. She has beautiful notes urging herself on to try harder to do the job more fully.

But in terms of this project also, of going where she had been and seeing it, you know, eighty-odd years later and talking to people there, one of the things that was incredible to me was that when I went to a shelter for people who didn’t have shelter, and when I went to a migrant labor camp, and when I approached my friend whose grandparents had been interned at a Japanese internment camp during World War II, and when I went to an encampment of people who are living without shelter, I said, “I’m doing this project partly because I’m following the footsteps of Dorothea Lange. And I’m just doing a project where I go places she might’ve photographed, and talk to people about what’s there now.” And the thing that was incredibly moving to me is I just described a very broad swath of life. Maybe people who haven’t made it into an art museum in a really long time. And everybody knew who Dorothea Lange was. And everybody seemed to be grateful and wish to talk on her behalf.

And it was this feeling that everybody seems to understand that Lange had left a gift for them. And they knew her. Everybody knew her. Everybody knew her and felt some kind of powerful response that provoked them to be generous with me. And I was very moved by that. That was really an incredible thing to uncover.

CUNO: I love the term that you use for the poems, “roadsongs.” Would you read “June Roadsong: 99-North to Fresno” for us?

TAYLOR: Sure.

“June Roadsong: 99-North to Fresno”

Calipatria, Indio, Neeland / The Salton Sea: Joke poster: Art project / —the last resort— / graffiti shops shuttered / till it seems we’re just driving / the wild wall of freight trains / the long ocher haul / of the basin towards Bakersfield: / Pupusas & roses / motor lodge motor inn / parakeets palominos kitchenettes cabins / a potholed valley of derricks. / Bowing black spindles / those lean rusty gleaners / suck ancient ferns / & we pass green peaches / netted against birds / & mountain snow / is a scrim in the distance / above one barn crumbling / in lattice-work light—

CUNO: Now, this is a poem that’s about your experience traveling, right?

TAYLOR: Yes.

CUNO: But it’s capturing her experience, too.

TAYLOR: There was a kind of overlay there that I was feeling all the time. And another conceit of the book is, there’s these poems that are— I call them the “Dear Dorothea” poems, where I write her a letter from the present into the past. And that’s one of the things that lyric poetry is do, is sort of speak to somebody that will never receive the letter. I call it the power of audacious address.

But the sense of wanting to report back to Dorothea what I’m finding and seeing, but also looking a little bit through her photographs and her lenses. So one thing that she does often is that she has these pictures with billboards. And there’s a famous one called On the Road to Los Angeles, where these guys are carrying bindles on their backs. And they’re walking up the road away from us, underneath a big billboard that says, “Next time, try the train.” And of course, they’re not gonna try the train. And there is that feeling of paradox that we’re somewhere between the America that is being advertised and the America that we experience. She gets that so beautifully.

But she loves billboards. And so in my poem, a different poem, where I’m driving again on this road, 99, which is the kind of like beautiful and ugly and industrial and— or agricultural road that cuts through California, and I think has the most traffic accidents of anywhere in the country—I mean, it’s a fast, narrow, dangerous road that transports fruit and passes fields and ends up in lots of subdivisions. But I ended up, as I was driving this road, making a note of all of the billboards, because I thought, okay, Dorothea Lange would see the music of these billboards. Or Dorothea Lange would find these billboards funny.

So it was that kind that I tried to do as I’m traveling around California. And in some ways, what I like to say is that Lange was my camera. You know, she was going around with a camera, but I was also trying to look through her photos as a way to approach seeing this state that I grew up in and where I live again now.

CUNO: What about Note to Self?

TAYLOR: Yes. So I did read maybe a thousand pages of Dorothea Lange’s archival notes. And lots of them really are just about externalities. They’re about the conditions that people have, they’re the lists of plants that they have planted in their garden, they’re about how much money they make and how much money they’re gonna need to spend, and a lot of economics of getting by, as well as those beautiful staccato quotes.

So you know, when I say that I’m using her notebooks, sometimes people think I’m using her journal. But it’s not very personal. There’s really very little. Occasionally, she tells herself to call her son, like, “Call Dan.” But it isn’t interwoven with many deep kind of introspective meditations. However, she does have these notes to herself. And I took them and I smashed them together into one poem.

“NOTE TO SELF”

Possible title: / TO HOLD THIS SOIL / NOTE TO SELF / General Theme of Book / “People left stranded by the outwash of industry in America” / NOTE TO SELF / US-99: THE SPLENDOR & THE REST OF IT / Note: young trees / Note: poor man’s canyon / a subject on the move / NOTE TO SELF / really do the work / follow the whole travel / DESTINATION UNKNOWN / 1. The Method / 2. (this still blank) / —a book on the conditions of US—

CUNO: That’s funny, I read that as a note on the conditions of U.S.

TAYLOR: It could be that, too. But I think I feel the “us” in it very much.

CUNO: Now, the poem is opposite a photograph. Explain the layout for us and— I assume you chose the layout?

TAYLOR: I did. I worked with Sarah Meister. And this picture that’s next to it was one candidate for the cover, but we didn’t want something so pastoral. But this is a beautiful dirt road edging the fall of the cliffs into the sea, and a farm kind of plowed all the way up to the edge of the cliffs.

And this kind of sense of the far west that we live in and the edge of the continent and trying to plant every last inch before it cascades down to this beach below. And those of us that have driven the coast of California will have seen this many times. It’s very, very beautiful, and it has a kind of haunting quality of sort of gripping, gripping the edge of the land and trying to get the last little bit of subsistence from it.

CUNO: And Mazie, why do you think Lange’s work works so well in black and white? And then did she ever do color photography?

HARRIS: I guess first I should say that I think we should have poets write all of our wall labels. It’s so beautiful to hear you describe photos; it’s like a true pleasure. So thank you for that.

The black and white, I think, does some of the work that Tess is talking about; it strips away distractions, it focuses our attention. She was really artful in cropping her images to help focus attention on telling details. The gesture of a hand, lived-in skin, the play of light, these hand-written signs, these mass-produced signs. So there’s this heightened awareness in black and white, where you’re able to really, really look at what he’s trying to show you.

I should note, black and white film was calibrated for white skin, so it wasn’t great at capturing a wide range of Americans. And some of the younger photographers who were working for the Farm Security Administration did start to try to shoot in color. Kodachrome movie film was introduced in the 1930s, and by the late 1930s, you were able to get color film in canisters or sheets. So photographers did have access to it, but it was incredibly expensive to print in color. The great scholar Sally Stein has worked on this topic, and she explained that for the most part, color photography was used for advertisements. So gelatin silver prints, these black and white photographs with which we’re so familiar, they signaled information; and color really signaled a kind of commercialism at the time.

CUNO: What about this image of the map of California, called Rural Rehabilitation Division, Proposed Location of Initial Camps? And is this something that you found in her archive? Or is this something that came from some other source?

TAYLOR: No, no, these scraps are from her archive. I didn’t get exactly the notebook images that I was copying from the Oakland Museum, because they weren’t available in a form that was digitally transferrable the best possible way.

But this is a page from one of her reports that she was making. And one of the things that she was doing with Paul Taylor is really urging that there be decent housing in places where people passed through to pick crops. And in fact, working with various organizations to be sure that there were places where people could sleep and have sanitary, you know, toilets, places to hang up their laundry and do their laundry. Otherwise, people were living in their own tents, that were kind of pitched in the mud, and working all day and coming back and really only having the ditch. And this was, you know, not healthy and not good for labor or food or any of it.

So this is a proposal of a kind of a reform that she’s working for. And to some extent, that has come true; if you go around California, there are these places where people who are migrant pickers of fruit can stay. And in other places, if you go, you’ll find that they have since been torn down. And that was the case in Imperial County, where people were— They were coming as migrant workers, to work in fields, but there wasn’t really housing for them. And so, you know, it’s a kind of a mixed bag, if you look at the legacy of that now.

CUNO: So this map has indications on it as to what grows in certain places—cherries, hops, prunes, asparagus in one place, vegetables, peas, lettuce in another place, apricots, potatoes, cotton, onions and so forth. Why were they distinguishing where on a map in the state of California, certain things grew?

TAYLOR: Well, this is the life of some people, to follow the crops from the south to the north; to pick one field, and when that field is empty, go to the next field and show up to work. And so she’s showing the maps of these migration patterns from the south to the north as things ripen. And it is, you know, I have to say, another one of these 1930s documents that’s just physically beautiful, you know, in the way that maps and old fonts and yellow paper are sometimes just beautiful to us.

And again, also these lists of crops are— have this tenderness to them. “Cherries, hops, prunes, asparagus, peaches, peas, grapes, cotton, grapes, peaches, apricots, vegetables, peas, lettuce. Peas and other vegetables. Berries, walnuts, lettuce, hay.” So you know, I guess it’s just a list of agricultural products, but somehow, laid out in this map there’s a tenderness to it that I really love.

CUNO: Now Mazie, after Dorothea Lange died of esophageal cancer, on October 11, 1965, in the Bay Area, at the age of 70, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a retrospective. It was the museum’s first retrospective solo exhibition of photography by a woman. Tell us about that exhibition and its importance.

HARRIS: Lange had struggled with her health for many years, but she remained committed to photography, even when she wasn’t able to shoot as regularly. At the end of her life, she was working really hard to encourage support for an initiative she called Project One, which she hoped would support photographers who were interested in capturing everyday life, the sorts of records of everyday existence that she and her colleagues had produced in the 1930s.

And she wasn’t just interested in images of impoverished or disenfranchised Americas, but also in portraits of people who allowed that kind of inequity to go unchecked. So she was really engaged with photography, even when she wasn’t as active in making it. She’d been featured in a number of prominent exhibitions at MoMA, at the Museum of Modern Art, and had helped with the layouts of some of them, really weighing in on selection, helping to solicit work from other photographers.

And in early 1964, the curator John Szarkowski proposed a retrospective of her work. But she received her cancer diagnosis just a few months later, so she really devoted the last of her energy to the project. She took over a lot of her house to work on the layout. She had a film crew there, who was making a documentary about her, and captured these preparations. Knowing that the end was coming, she really threw herself into making prints, into discussions about the layout.

Just days before she passed, she was really focused on what paper you should use to print various sections of the exhibition. And the exhibition opened just a few months after she died.

CUNO: Tess, would you read Nipomo, Sunday 2019 for us?

TAYLOR: Sure. So this is going back to Nipomo, where she photographed that famous picture that came to be known as Migrant Mother. And part of the project of the book was just to go to the places she had photographed and look what was there now. So this is my record of that trip.

Nipomo; dusty Sunday, eighty-two years later. / Strip mall off the freeway / swapmeet wildflowers stucco heat / Above where pea fields were / 3 beds 3 bath FOR SALE / & horse trailers next to / the “new community”: Monarch Dunes. / Below: Half-hidden valley, / the parched walls of Guadalupe, / & long strawberry fields— / Starting out in rain / Lettuce fields pea fields Salinas Valley / —I’d go back if I could ever get the money— / to Stockton Gridley Lindsay pickers needed / work lemons work oranges work peas / Gritty sand verbena // greenhouse lavenders; / somebody’s lost flier calling for / 1.1 million dollars: TRILOGY ESTATES / The sign, dear Dorothea, / instructs please inquire / In bold face, she underlines: NO PROMISED LAND / * / Alejandra & Sylvestro / hoeing squash on Sunday / big work a little field but / Roger who is 8 says we can / talk if no one’s watching / * / & the peas wait strung / in rich dust under the bluff; / hoe & stool & boxes / inside the snaping wind / * / Kids on Sunday kick / their ball between greenhouses / and below the trestle bridge / redbreast blackbirds rise— / Rancho #1, Rancho #2 / Aceptamos Applicaciones / & Propriedad Privada. / No children visitors dogs / NO TRESPASSING / TU SEGURIDAD ES PRIMERO / * / where we was we wasn’t rich but everybody knew me / Beyond the last field at sunset / dunes ridge & buck the sky. / Other planetary mineral / under this sharp moon. / Wild churning Pacific—/ (as if this could give way or begin again—) / * / Monday 7 a.m.: Road full / trucks out of Santa Maria/ workers opening boxes / & children dropped at school / the fast work of the lettuces / in highwaisted waders / hard rhythmic toss of kale; / & row by thorny row; / the artichoke procession / on after the truck / * / What people need: / Groceries tobacco meat some vegetable some fruit / At the Dorothea Lange Elementary School / the secretary frowns: We don’t study her. / At Jocko’s Steakhouse, the bartender nods: / My family’s been here 150 years. / Yeah, we know about her. / How she photographed that woman. / The people coming through. / Yeah, the migrant mother: / People in this town are still always coming through—

CUNO: That’s moving and beautiful. Now you’re working with other artists who are pushing to have renewed investment in the arts, as a form of economic and social repair. Tell us about that project.

TAYLOR: Yes. As part of this moment, when we’ve become really aware of all of our precarity and the precariousness of our lives in this economy, where we can become sick and a pandemic can hit; and actually, after a time when we’ve lived through a lot of civic unrest and public violence, there’s a group of us that’s beginning to say to ourselves, “What do the arts have to do now? And what could we offer now, as part of repair?”

And one of the things that I’m thinking about as we come up towards the infrastructure bill, is thinking about art as infrastructural to our wellbeing. That feeling that people have of being seen, of being able to make.

I have an article coming out in Harper’s Magazine this June about the role of the arts in the peace process in Northern Ireland. I was a Fulbright there.

But it’s also part of this attempt to report on some of the work that’s happening. There’s a group of actors that are advocating for something called the DAWN Act, Defend Arts Workers Now. And other groups of artists who are trying to say, how can we invest in this force as part of the repair? What could a Farm Security Administration do now? What could a project of gathering oral histories do now? What could we do if we asked America’s artists to work building programs that brought people together and made us feel seen, and helped Americans witness one another once again?

And so that’s just very dear to my heart. If you’re interested in it, reach out. We’re starting a little bit like Archibald MacLeish, with just a series of conversations. We had one at Politics and Prose called “Do We Need a Cultural New Deal?” And there will be others in the fall.

CUNO: And that’s a bookshop.

TAYLOR: Yeah, Politics and Prose is a bookshop in Washington, D.C. And five writers came together and had this conversation, Do we need a cultural New Deal? Five writers on the arts of repair.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, Mazie, let me give you the last words.

HARRIS: This discussion makes me wonder about our textbooks that we use in schools today. I wonder how much of what we know about Lange and these other photographers is because we saw it— It was the images that were used to tell us history. So that’s the project that I think I’m gonna give myself after this, is to go look at some of the textbooks and see if that’s why we all have this familiarity with these images.

But I think I’d like to end by talking about this phrase from one of your poems, “latticework light.” I remember reading that some of Lange’s photos that had latticework light would be rejected because the people in D.C. thought it made it look as though the people were in prison. And so I like your recuperation of this phrase about the latticework light. And I’m so grateful to you for sharing your words with us.

TAYLOR: You know, that latticework light is somewhere between indoors and outdoors, and it kind of applies a provisional house, doesn’t it, to have a partial bit of light and shade. And I think she was always thinking about that: what shelters the body? What shelters does the body need? And that tenderness and care runs through it. And anyway, thank you, Mazie for that comment. And it’s been really lovely to join you.

CUNO: Mazie and Tess, thank you both very much. It’s been a pure delight for me.

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

TESS TAYLOR: It was really powerful to be on the road following her footsteps. It just gave me an i...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Very interesting topic. Please recommend where more information is available about the children shown in Pledge of Allegiance, Raphael Weill Elementary School – Getty