Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“When Cunningham passed away, I think in part her reputation was based on her personality, the fact that she had lived so long, the fact that she was full of witty quips, and she wouldn’t let anyone boss her around. But I think in some ways that eclipsed the work.”

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1883, photographer Imogen Cunningham joined a correspondence course for photography as a high schooler after seeing a magazine ad. Over the course of her 70-year career, Cunningham stirred controversy with a nude portrait of her husband, photographed flowers while minding her young children in her garden, captured striking portraits of famous actors and writers for Vanity Fair, and provided insight into the life of nonagenarians when she herself was in her 90s. Although photography was a male-dominated field, Cunningham made a name for herself while also supporting the work of other women artists. Her long, varied career is the subject of the new exhibition Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective at the Getty Center.

In this episode, Getty photographs curator Paul Martineau discusses Cunningham’s trajectory, focusing on key artworks made throughout her life.

More to explore:

Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective explore the exhibition

Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective buy the book

Transcript

James Cuno: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

Paul Martineau: When Cunningham passed away, I think in part, her reputation was based on her personality, the fact that she had lived so long, the fact that she was full of witty quips, and she wouldn’t let anyone boss her around. But I think in some ways, that eclipsed the work.

Cuno: In this episode, I speak with Getty curator Paul Martineau about photographer Imogen Cunningham.

Born in 1883, photographer Imogen Cunningham was more than eighty years old when she received the first major study of her work in the winter 1964 issue of Aperture magazine. Two books followed, in 1970 and 1974. Then, after her death in 1976, numerous publications appeared, including Imogen Cunningham: A Portrait by the photographer Judy Dater.

The Getty’s exhibition, Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective, is the first major presentation of her work in the United States in more than thirty-five years. In the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, Getty curator Paul Martineau and independent curator and art historian Susan Ehrens explore the length and breadth of Cunningham’s long and illustrious career.

I recently visited the galleries, where I discussed Cunningham’s work with the exhibition’s curator, Paul Martineau.

Thank you, Paul, for speaking with me on this podcast episode.

Martineau: Oh you’re very welcome.

Cuno: Now, this is the first major exhibition of Imogen Cunningham’s work in the US is more than thirty-five years. Why is that?

Martineau: I think there’re several reasons. One is that Cunningham never wanted to be labeled one thing or another. She had a vast amount of work, in many different styles and themes. And she said she worked by instinct an she was gonna leave it to the viewers to figure her out. So I think that it’s very hard to kind of put her in one spot or another. So that really didn’t help people assess her work properly.

Cuno: Now, what was her background like? Where was she born and how did she come to work in photography?

Martineau: She was born in 1883, in Portland, Oregon. And while she was a child, her parents moved several times, finally settling in Seattle. She comes from meager circumstances. Her father operated a street-grading business, as well as a coal and wood delivery business. When she was in high school, she decided that she wanted to become a photographer, and she answered an ad in a magazine and joined a correspondence school. And for fifteen dollars, they sent her a camera and the instructions. So initially, she was self-taught.

Cuno: Now what about her father, though? I think I have some memory about his influence on her.

Martineau: He was a very interesting person. He was a vegetarian and a teetotaler, a freethinker. And he didn’t think the Christian religion had done very much for the world, so he would make taffy on Sundays to dissuade the children from going to Sunday school.

She had an open mind, and that’s something that he had in spades. He wasn’t a judgmental person. He really believed in a kind of world that could be a much better place than it was, if everyone behaved properly. And he also believed in hard work. And this is one of the things that Cunningham really kept close to her as she proceeded in her career.

Later on, when the United States exploded the atomic bombs over Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Cunningham began wearing a peace symbol. And during the Vietnam War, she was a vehement pacifist, and often recommended her friends not to join the war. And she received some flak from her more conservative friends for this opinion.

Cuno: Who was Frances Benjamin Johnston and what was her association with Cunningham?

Martineau: Frances Benjamin Johnston was a photographer and photojournalist, one of the first pioneering female photojournalists, who worked in Washington, D.C. She was appointed the official White House photographer for five different administrations.

And in 1897, she wrote an article for Ladies’ Home Journal called “What a Woman Can Do with a Camera.” And that was something that I think really inspired Imogen. In 1913, Imogen wrote her own article about photography as a profession for women.

Cuno: How did she manage her first trips to Europe?

Martineau: Imogen received a scholarship from her sorority, and that allowed her to travel to Dresden and study photographic chemistry.

Cuno: Why Dresden?

Martineau: There was a school that was renowned for study, the study of photographic chemistry. So on her way, she stopped in London and met Virginia Woolf and Alvin Langdon Coburn, who was a pictorialist photographer who was quite famous.

And we believe this picture, which is the self-portrait with plaster cast of the Elgin Marbles, was probably made in London in 1909 or 1910. And it shows her seated in front of a relief. And she’s holding a sketchpad and a pencil, so she’s appearing as though she’s drawing from the Antique. And it’s interesting ’cause she places herself in the history of art, going back to the ancient Greeks.

Cuno: So when she came back from Europe to Seattle, she was working in a studio in Seattle, and we have a photograph of that studio here. Describe it for us and tell us how distinct it might have been at the time.

Martineau: It’s a little cottage in the woods. And it’s outfitted with all manner of art prints. And Cunningham purchased some dolls when she traveled to Germany so she could distract the children of her portrait sitters.

She was photographing mostly women and children. She promised people that she would make a good likeness and that it would be an artistic photograph, devoid of the kind of routine backdrops that photographers were using at the time.

Cuno: How did she advertise her work?

Martineau: She took out an ad in the newspaper. And she also advertised by word of mouth.

Cuno: What kind of market was there at the time in Seattle?

Martineau: It was a thriving city, so Cunningham had lots of opportunities to make pictures for people. When she began, she was the only female photographer working in Seattle, so I think that was a selling point.

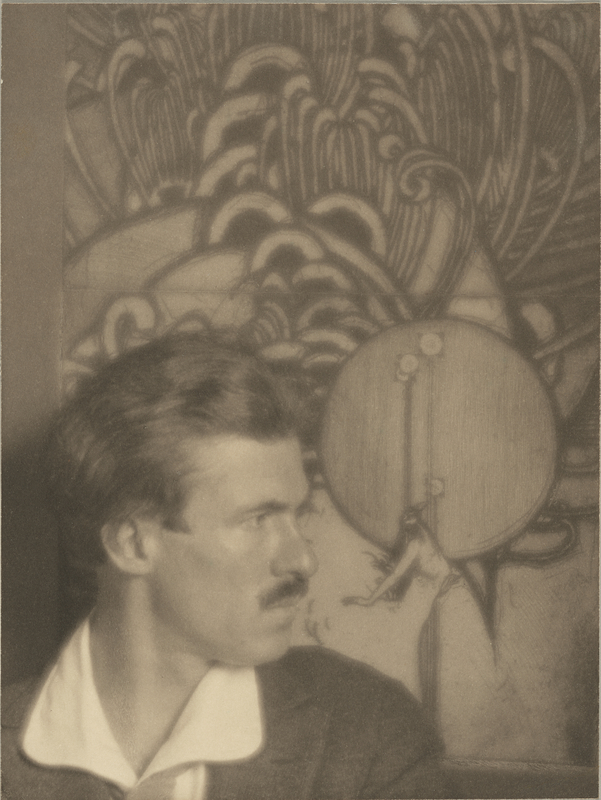

Cuno: Now what about these photographs? There’s a portrait of the etcher Roi Partridge.

Martineau: This is a portrait of Roi Partridge, who was an etcher and was Cunningham’s husband. They married in 1915. And she made this picture of him sitting in front of one of his etchings. It’s a large-scale work, where he’s pieced together different sections of paper to make it larger.

And they fell in love by correspondence. He was in Paris; she was helping support his stay there by selling his etchings. And he would send letters to her, and when he came back, as World War I was starting, to Seattle, they got married.

The picture next to it shows him on Mount Rainier, and he’s nude, which is very unusual, for a female photographer to be making a male nude. And when the newspapers and magazines in Seattle got hold of the news, they called her an immoral woman.

Cuno: Now, there’s considerable mention of Mills College in your account of Cunningham’s career. Other than its being a women’s college and the importance that might’ve held for her, what was Mills College’s role in Cunningham’s career?

Martineau: Cunningham’s husband, Roi Partridge worked at Mills, teaching art and also running the art museum there, and Cunningham was a faculty wife. And she took advantage of all the opportunities of the lecturers that were coming in to give talks or dancers coming in to give performances, to take pictures of these people.

Cuno: Now, Cunningham photographed the composer Henry Cowell, an important figure in avant-garde music at the time. And she photographed Martha Graham and other dances in the twenties and the thirties. How important were music and musicians to her art and practice?

Martineau: Cunningham loved creative people. She loved being around them, she loved photographing them, and she had a deep respect for artists of all kinds. She took the opportunity to photograph all the dancers that came to Mills College. And then in the mid-1930s, she was invited to go to the Cornish School of the Arts in Seattle and help them make a brochure. She photographed all the musicians at the school.

She met Martha Graham in Santa Barbara, and Martha agreed to make some pictures with Imogen. So the picture that we have shows her coming out of a barn. So there was a kind of dark space that she’s emerging from, into the warm California sun. And that’s why it’s so beautifully contrasting light and dark.

Cuno: Now, this gets us to the point of 1921. So this is a couple decades into her career. What was it like by this time for her?

Martineau: There was a big shift for Cunningham. In 1917, she moved from Seattle to San Francisco. And she took a few years off to care for her young children. She had one boy and then she had twin boys, so she had three children in two years.

Cuno: What about the San Francisco Women Artists? What was its history?

Martineau: That group was started in the 1880s by a number of like-minded women who were independent—they were all exhibiting artists—to provide other opportunities for exhibition for female artists.

Cunningham decided to join that group because she felt as though women didn’t have enough opportunities to exhibit their work. And it was a great space for networking between women. Cunningham was involved in a very male-dominated field. And I think having these friendships really help her to gain confidence and influence other people. Cunningham was always looking to be a mentor for younger people. And I think this gave her the energy to go out and help others.

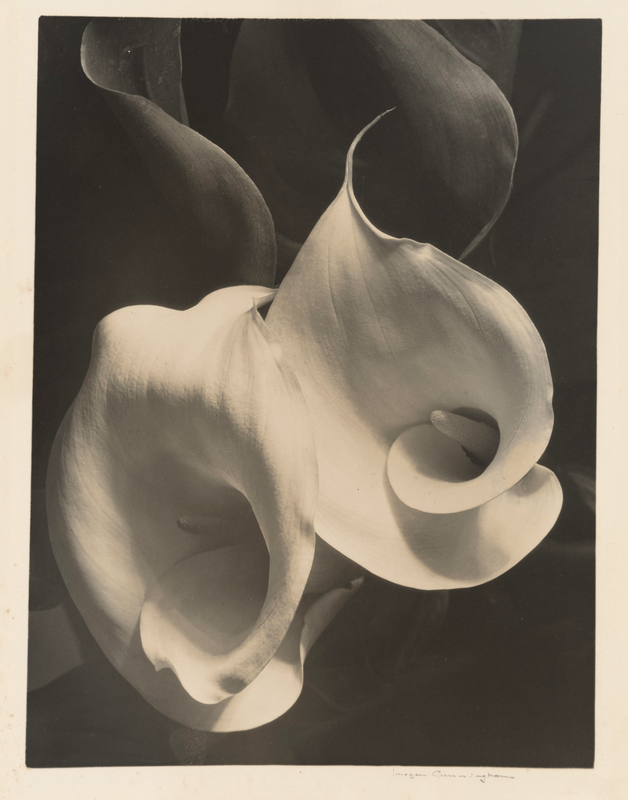

Cuno: Now we’re in 1925, 1929, a portrait of two calla lilies. Tell us about the transition from the landscape setting to the individual objects setting.

Martineau: Between 1917 and 1921, Cunningham makes an abrupt shift away from soft-focus imagery, which was known as pictorialism, towards early Modernism. And her pictures become more intensely defined, and she focuses in on the plants in her garden.

One of the reasons why she started photographing the plants was that she had three small children and she didn’t drive, so she was chasing around the garden, and she took the opportunity to stop and make a few pictures. One of the interesting things that she did, as well, is that she would often put a black cloth or a black board behind the plants in her garden, so she could photograph them in natural light and it would look like she had taken them into the studio.

Cuno: What about this photograph of flax? It seems to be so abstract, almost.

Martineau: Yes, yes, that’s what attracted us to it. It looks like a blade of grass that’s just standing up, very vertically. And she’s really eliminated everything else from the frame, so you just have this kind of white backdrop. And it’s startingly[sic] modern. It reminds me of a Barnett Newman Zip.

Cuno: Describe to us this rubber plant photograph.

Martineau: The picture of the rubber tree plant is cut off. It’s kind of creating a diagonal trajectory throughout the picture, which gives it energy. Cunningham took a black board and placed it behind the plant. And you can feel the warmth of the sun illuminating the leaves of the plant.

Cuno: Who was she inspired by, by this time?

Martineau: I think she was looking at the plant work of Karl Blossfeldt, who was German. And she received some books on his work, and that helped her devise these compositions.

Cuno: Now, some of these photographs, the one we just described, the rubber plant, for example, these very sharply-contrasted blacks and darks and lights. Some of them are much softer than that.

Martineau: Yes. Some of ’em are softer. I think that she wanted to kind of embrace the organic nature of the forms. And in other times, she wanted to sharply define the effect of light and dark on the plant.

Cuno: What about Edward Weston and his photographs?

Martineau: Edward Weston was a friend of Imogen’s and they inspired each other in the early 1920s. And in some cases, the pictures look similar, and it’s really tough to say who inspired whom.

In 1929, he included her work in the Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart, Germany, where she was heralded as one of the early American Modernists.

Cuno: What about her still life photographs? How do they compare to Edward Weston’s?

Martineau: I think they’re very different than Weston’s. His are about finding the universal forms in all things, and hers are more concerned with the light and shadow on living things. So there’s quite a distinction there, I think, between those two different poles. His tend to be anthropomorphic. You know, you see in the shape of a pepper, a kind of human form. And in hers, it’s really a celebration of the light illuminating the forms.

Cuno: Now, tell us about her portrait of Alfred Stieglitz standing in front of a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe. How did she get that picture, and what was her relationship with the Modernist photograph?

Martineau: She really wanted to meet Stieglitz, and she went to his gallery in 1910, when she was traveling back from Dresden. But she was too afraid to speak with him. So in 1932, she had the opportunity to travel to New York, and she brought some of her own glass-plate negatives and borrowed his camera to make the picture.

And she had him stand in front of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Black Iris. And she made seven exposures and they all came out, despite the fact that she didn’t have a light meter and the camera was so rickety that it took an eternity to stock rocking on its tripod.

Stieglitz is closely framed, and his expression is one that includes some respect, but also some caution.

Cuno: This is a wall of portraits. Everyone from the photographer Brett Weston to Edward Weston and Margrethe Mather to Martha Graham, the dancer, to Gertrude Stein, the writer.

Martineau: Cunningham took the opportunity to photograph Gertrude Stein when she came to San Francisco to lecture at Mills College in the 1930s. Many of the people who are featured on this wall are either photographers or part of Imogen’s family. There’s a picture of her mother in the center, where she’s been melded with some kitchen utensils, signaling her role, her domestic role. And then adjacent to that is her father, with a very long, silvery beard. He looks like Father Christmas.

And then to the right of that is a picture of Cary Grant. Imogen was invited by the editor of Vanity Fair to go to Hollywood and photograph men. And he asked her what type of men she wanted, and she said, “Give me the ugly men. They don’t complain and they’re not vain.” So she went to photograph Cary Grant, along with other celebrities like Wallace Beery and Warner Oland. And later on in her career, when she was on the Johnny Carson show, he asked her about whether she thought Cary Grant was ugly. And she said, “No, he convinced me that he wasn’t.”

Cuno: Now, as there was a wall of portraits, there’s a wall of nudes. Tell us how— where these were shot and taken, and how she was attracted to them.

Martineau: After she had the little mini scandal in Seattle concerning her portraits of Roi nude, she put off making nudes for a little while. And then in the twenties, she started to get back into them.

And these pictures were made in various locations—some in Los Angeles, some in Seattle—showing various sitters. The one here in the center, which is called Torso, is actually two torsos, a torso of a man and a torso of a woman, and they’re intertwined. And we don’t exactly know who they are, but some scholars think that it might be Edward Weston and Margrethe Mather.

Cuno: Now here’s a portrait of the sculptor Ruth Asawa. Tell us about the connection that the two might have had with each other.

Martineau: Imogen and Ruth were introduced to each other through Imogen’s son, who was a photographer, who was doing mostly architectural views. And Asawa’s husband was an architect. And they had a forty-three year age difference between Ruth and Imogen. But Imogen loved to be surrounded by younger people, especially creative artists like Ruth.

And both of them believed that they shouldn’t have to sacrifice their art to have a family life as women. They were both very determined to have their work celebrated and exhibited whenever possible.

One of the things that made it possible for them to have careers while being mothers is that both mediums—the sculpture that Ruth was doing and the photography that Imogen was doing—were portable. So they could do them in the kitchen when they were sitting with the kids, or in the garden when the kids were running around. I think that was one of the secrets.

Cuno: What about the painter Morris Graves? What kind of relationship did Imogen have with him?

Martineau: Cunningham photographed him on a number of occasions. And I think the relationship goes back further than that. He was based in Seattle for the first part of his career, and then he moved to California after that. There’s a very good portrait of him from 1950. And then later on, he wrote to Cunningham, asking he she would come and make a new portrait of him.

And that was in the mid-1970s. So she did. And she was walking around his estate with him and she asked him if he would enter the pond that he had there, so she could photograph him partially submerged in the water. And he refused. And she asked him again; he refused. So she took a picture of him standing near the pond, and she took a picture of the pond, and then she melded them together and she put him in the water, in her darkroom.

Cuno: Now, here’s a portrait of Minor White, the photographer. Why is this in the exhibition?

Martineau: Minor White was a friend of Imogen’s, and he understood the difficult position she was in as she was turning seventy, and she started to think, you know, what am I doing? How am I being assessed? Is my career moving forward, or am I just kind of stalled?

And she sent him a letter. She was complaining about her situation. And he agreed to help her put a collection of her work at he George Eastman House. And he also agreed to give her her first monograph, at age eighty, in his magazine, Aperture.

To celebrate that announcement, Cunningham decided to make his portrait. She asked him to go out into the garden. She hung a black cloth on her white fence, and she broke off some branches from a tree, a shrub in the yard, and put it behind him and made the picture. And when he published the work in Aperture, he described the sitting. And I’ll just read that to you.

“Listening to the overtones of her words, a warmth was communicated. Then her phrases became beautiful. This was a wonder to watch, and I gave myself up to the light that seemed to diffuse outward from her face and head. Only then did I realize that it was her own light, whether she admitted it, or even knew it.”

Cuno: That’s great. Now, in 1960, she traveled abroad. What prompted her to travel abroad?

Martineau: 1960 was the first time that Cunningham really had any money since the time she was divorced, in 1934. Minor White, who was working in San Francisco and became her friend, had moved to Rochester to work with Beaumont Newhall at the Eastman House. And he’s the one that arranged for a collection of her pictures to be purchased. So with that money, she made two trips—one in 1960 and one in 1961—to travel to Europe and meet some of her photographic idols.

On one trip, she met August Sander, the photographer who photographed the German people of the Weimar Republic. And then on another trip, she sought out Man Ray in Montparnasse, and she took a very conventional picture of him. And when she got back, she realized that it was too boring, so she turned it into a Duchamp, by moving her negative and having it look like his face and body were cascading down the surface of the picture.

Cunningham was one of the first people to see the Nude Descending the Staircase, by Duchamp, shortly after it was purchased by a Berkeley collector, from the Armory Show in 1913. He brought it back and he installed it in a staircase. And he invited people over to look at it. Cunningham went.

Cuno: Now, a decade later, she was photographed by the much younger Judy Dater, most memorably in Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite, in 1974. Five years later, in 1979, Dater published an important monograph, Imogen Cunningham: A Portrait, which includes interviews with Cunningham’s family, friends, and colleagues. What was their relationship like? That is, Imogen and Judy Dater’s. And did it mark a kind of revival of interest in Cunningham’s career?

Martineau: Cunningham and Dater met in the late 60s or early 70s, I believe, and it was at a photographic workshop. They both were really interested in portraiture, and I think they found that they had a common bond in that. And they became friends.

And after Cunningham died, Dater had collected information, did oral histories with all her friends and colleagues, and then assembled this book, which did lend itself to a revival of interest in Cunningham. Around the time that she died, I think that Cunningham was being celebrated, in part, because of her age. She was ninety-three, and she was still a working artist. She was sort of the Grandma Moses of photography.

Cuno: Cunningham was active until she died, but at that time, she was involved in a project called After Ninety. Tell us about that.

Martineau: When Cunningham was ninety-two years old, she took on a new project to create pictures of people of advanced age. And she went to hospitals and looked up her old friends, sought out people who were also over ninety, to make their portraits. And Cunningham estimated the project would take two years. She was one and a half years into it when she passed away, and the book was published posthumously the following year, in 1977.

But one of her friends inquired, you know, “Are all these people that you photographed as active as you?” And she said, “Well, I wouldn’t call them active, but they were alive.”

Cuno: Well, before then, at age seventy-five, she divided her photographic career into three periods. What were those three periods and does the division stand up still today?

Martineau: The three periods were related to the locations that Cunningham was living in at the time. When she began her career in Seattle, that carried her from approximately 1901 to 1917. Then she moves to Berkeley, and after a break, she resumes her career in 1921. And she lives in Berkeley and uses Mills College as a kind of way of finding photographic subjects.

And she decided then, in 1947, to relocate to San Francisco. And she purchased a bungalow in the Russian Hill neighborhood, at 1331 Green Street. And she remains there through the rest of her life. She passed away in 1976.

Cuno: When she died, what was her reputation like? And what is it like now?

Martineau: When Cunningham passed away, I think in part, her reputation was based on her personality—the fact that she had lived so long, the fact that she was full of witty quips, and she wouldn’t let anyone boss her around. But I think in some ways, that eclipsed the work. And I think this retrospective has gone a long way in reintroducing not only her work to a new generation, but also to scholars in the field who might know her most iconic pictures, but really don’t know the depth and extent and variety of her oeuvre.

Cuno: And that’s what this exhibition means to correct.

Martineau: Exactly.

Cuno: Well thank you, Paul, for speaking with me this morning. It’s a beautiful exhibition.

Martineau: It’s my pleasure.

Cuno: Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective is on view at the Getty Center through June 12, 2022.

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

James Cuno: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

Paul Martineau: When Cunningham passed away, I think in part, her reputation was based on her pers...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.