Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“Lamb’s objective was essentially to do Kon-Tiki in the Chiapan Rainforest. And he needed a lost city as a selling point.”

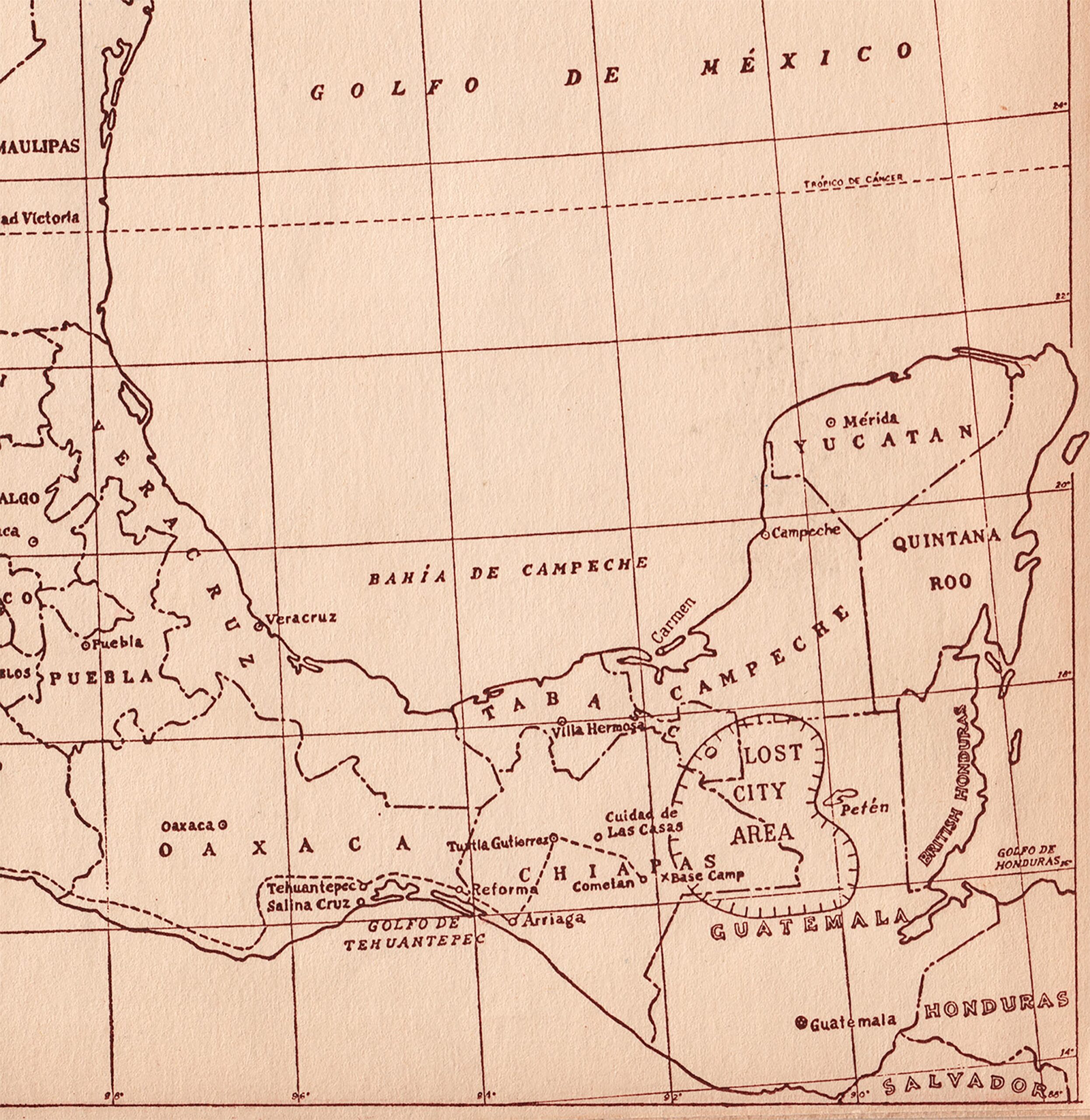

In 1950, American adventurers Dana and Ginger Lamb traveled to the jungles of northern Guatemala looking for Maya ruins and a story they could turn into a movie. There they encountered a rich cache of decorated structures made in the first millennium CE, including a particularly elaborate limestone lintel (a horizontal support above a doorway) carved by an artisan named Mayuy. Such objects had and continue to hold great historical, aesthetic, and spiritual significance for Maya people and descendants. Unfortunately, like many Maya ruins, the site has since been looted, and retracing the original locations of the displaced works is challenging.

In this episode, Stephen Houston, editor of A Maya Universe in Stone, explores the production and complex afterlives of these Maya objects. Houston contextualizes carved lintels within ancient Maya history and visual and spiritual practices, and discusses the fraught nature of their re-emergence in the twentieth century.

More to explore:

A Maya Universe in Stone buy the book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

STEPHEN HOUSTON: Lamb’s objective was essentially to do Kon-Tiki in the Chiapan Rainforest. And he needed a lost city as a selling point.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with anthropologist Stephen Houston about his new book, A Maya Universe in Stone.

In 1950, the American explorer Dana Lamb happened upon a Maya ruin in the tropical forests of northern Guatemala. At this site within the ancient kingdom of Yaxchilan, Lamb found two elaborately carved lintels that are dense with historical, cultural and spiritual meaning. Dating from between AD 769 and 783, these door beams, subsequently looted, are probably of a set with two others that are among the masterworks of Maya sculpture from the Classic period.

Lamb was notoriously reticent about where he discovered the carvings, turning his find into an archeological mystery at the heart of the new book A Maya Universe in Stone, edited by Stephen Houston and published by the Getty Research Institute.

I recently sat down with Stephen, the Dupee Family Professor of Social Science at Brown University, to discuss the importance of the Maya lintels and their afterlife.

CUNO: Thank you, Steve, for joining me on this podcast.

STEPHEN HOUSTON: It’s a great honor and pleasure, Jim.

CUNO: Now, give us an outline of the history of the ancient Maya.

HOUSTON: There are many, many different Mayan groups, thirty different languages or more, with varied histories. And so to some extent, each one of those language groups and the ethnic groups they represent have had their own varied history of research.

It is a civilization that really comes together as a literate one, with a copious tradition of carving, probably about 2500 years ago to, more or less, the beginning of the Common Era. And that’s when we start seeing very large cities, in fact, of a scale, of a magnitude that really is seldom documented even anywhere else in the world. And in addition to that, we are laying out the kind of cultural parameters for what will become Classic Maya civilization, which is the period I study.

And this is a courtly society; it’s focused on ancient kings, their courtiers, their immediate families. It really begins to take off in about AD 100 or so. They’re living in palaces; there are populations that are going into the millions; we have intensive agriculture, trade, economic tribute.

But beyond that, there are far more ethereal matters being discussed in the surviving textual record from that time and also in the imagery. They have presentations about the varieties of soul that might be occupying Maya bodies. There are chocolate recipes that are specifying, to a very great degree, what people might be quaffing in some of these festivities that we know that they celebrated. And then finally, it’s a time in which we have really pretty strong evidence for a kind of hegemonic empire that is centered on one important kingdom in particular, Calakmul.

And it’s also about that time, or maybe a century or so before, that there’s a lot of contact with the great city, the metropolis, of Teotihuacán, which is pretty close to what is now Mexico City. In fact, it’s being enveloped by the growth of that urban zone. It’s also a time in which they’re probably using a kind of lingua franca, the elites are speaking one language and it’s not at all clear that anyone else is communicating in that speech.

And then it concludes, I would say, with what we call the Post-Classic, which is a very tendentious term. It suggests that everything is with respect to the Classic period. But it really is a time with a profoundly different constitution of society, and suddenly things become much more opaque to us. In other words, the earlier periods, paradoxically, are much, much better understood. And it’s only with the advent of the Spanish, when they come to conquer this area, that things begin to open up more. The Spaniards are recording a great deal of information about the panoply of gods and the nature of Maya society at that time. And there’re also many, many devastations.

But the final thing I would say about this trajectory, Jim, that I think is worth mentioning, is that a stunning feature, even today, of all of these descendant Mayan peoples, these Mayan speakers, is that they have this kind of sustained cultural or ritual orientation that demonstrates just astonishing continuity over time. And it’s not so much in details, but it’s what you might say have to do with rituals, with covenants of duty, with relations to land, and indeed, to time itself.

And so that’s expressed in all sorts of rituals that are still ongoing in Guatemala, in Belize, in Mexico, and also in Honduras, in which we have supplications of deities and forces of mountains and water. So all of this tells us that this is obviously a changing group of peoples, but they’re so deeply grounded in this area. It makes them tremendously exciting to study.

It also gives us another level of, you might say, ethical or epistemological or interpretive responsibility, in that there are descendant communities that we need to address, and for whom we will frame how we come to conclusions in, I think, a very careful way.

CUNO: What’s the size of the descendant population of Maya today?

HOUSTON: Today, it’s very much close to a number of millions. And in fact, the largest indigenous group in the United States today are speakers of Mayan languages who’ve immigrated here. So they are very much part of the firmament of the United States, as well.

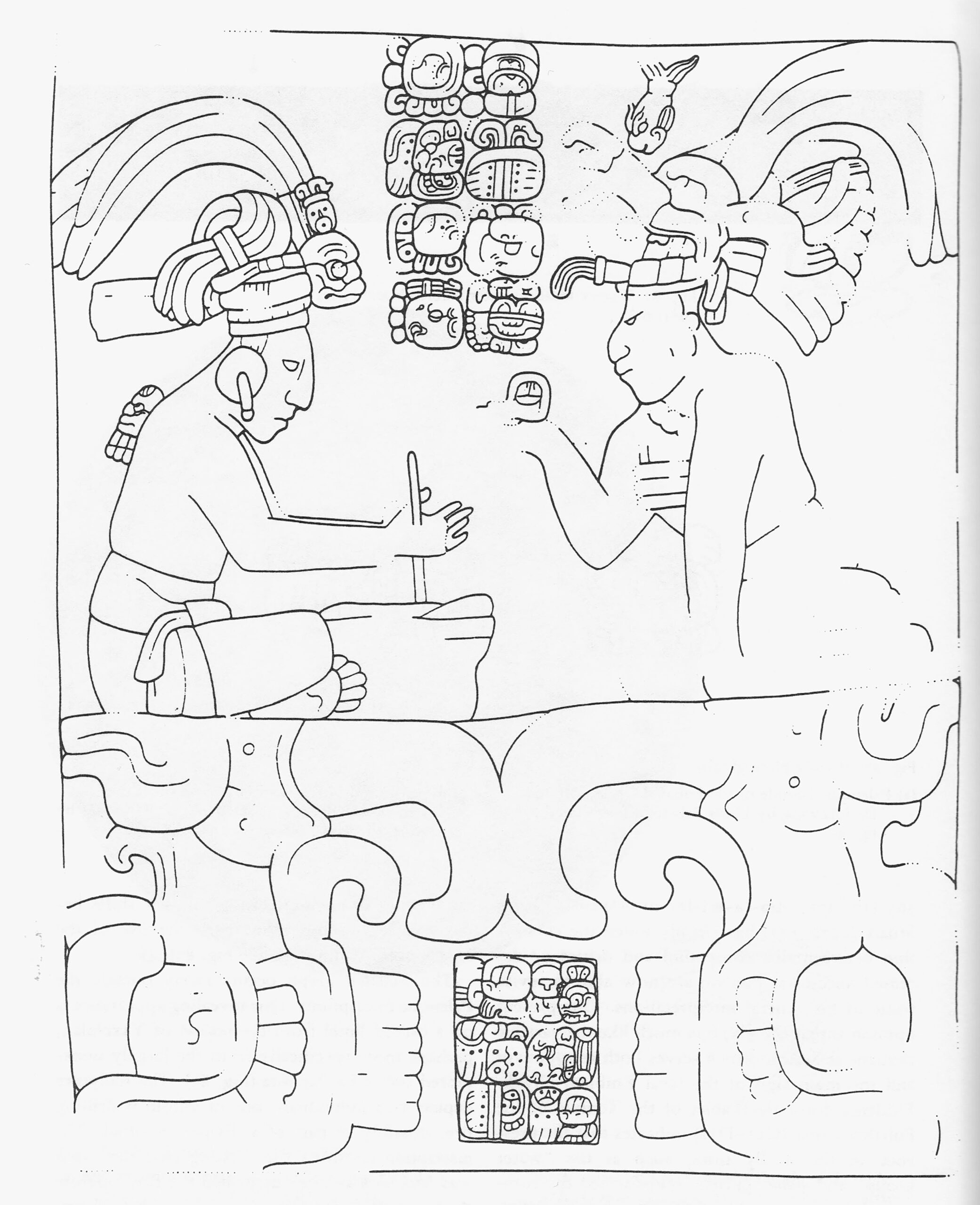

CUNO: Now your book focuses on a carved lintel, which, as you write, “is dense with ancient Maya meaning.” Tell us about the role of such carvings in ancient Maya culture.

HOUSTON: I think the way to look at this civilization is, again, to mostly pay attention to this Classic period that is more or less the first millennium AD. And that’s where we have a good purchase on what the Maya felt and thought about these kind of sculptures. They obviously, from an abundance of evidence, injected a certain life and vitality into their carving.

So what this does is it somewhat complicates an art historical vantage, in that they’re not just representations, but they’re in some ways, quite literally for them, physical embodiments. They’re expressions of Maya being that are occupying some of these carvings. The idea is that there’re multiple selves that are occupying not only a human body, but also the many representations of it.

The second thing to remember about these, though, is that all of these carvings have a certain physical involvement with the viewer. That is, the reception is, in itself, a fascinating part of the process of their emplacement on this landscape. So that if you see a stele or an upright stone monolith on a Maya plaza, for the Maya, it was a being or a ruler, usually, who is shown in perpetual, almost frozen, dance.

And so by walking around it, you’re, in some ways, participating in whatever kinetic activity that involved. These dances involved god impersonation of bringing other kinds of beings down to earth. Hieroglyphic stairways are also kinetically fascinating from an interpretive viewpoint because you, of course, walk up and down them, but what is often depicted on them, in terms of imagery, or recorded on them in terms of hieroglyphic inscriptions, would be a succession of rulers over time. The ancestors are people literally underfoot, and they’re recorded in sequence up and down the stairway.

Some of these stairways also show ball playing. And we suspect that there was a great deal of sporting activity that took place on or off of these. But really, what we’re talking about here are the lintels. And these were very much the center of the publication for the Getty. And the lintels are features of buildings that span doorways. They’re found in many, many palaces. I suspect most of them were of wood and have long since rotted away.

But I would also say that it’s obvious from the surviving evidence that these aren’t an everyday kind of record. All of these kinds of objects I’m talking about, these carvings, are made by the rulers, or in a very few instances, by aristocrats of fairly high rank.

The lintels are a little bit complicated in another way, in that of course, they are difficult to look at, in that once you get into one of these, or pass through a narrow doorway in a Maya building, you have to arch your back and bend your neck. It’s not a terribly comfortable position. And it’s already putting you in a kind of subordinate or supplicative position, in which you’re in some discomfort trying to access them. And these figures are always looking down on you, in a way that the Maya thought of the ancestors as doing on a perennial basis. And so all of this tells us that they were very much concerned with the physical placement of these carvings, but also how humans would interact with them.

And then the final thing to remember about all of these carvings is that they’re interacting with changing meteorological circumstances. This is a place and a general area with fierce sunlight at certain times of the year, and at other moments, that is very much muted by cloudy conditions. But the sculptures are always being modulated, to some extent, and I think deliberately so, according to the wishes of the carvers and their patrons, whenever someone walks up to them, whenever one wants to look at them.

CUNO: Now, when and under what circumstances was this particular carved lintel found?

HOUSTON: This lintel was first seen by an adventurer named Dana Lamb. And we know the exact date. It was April 7th, 1950

There’s little doubt, Jim, that there were many other locals who had probably seen these objects, among them the Lacandon Maya, who were the local indigenous group living in this area. But there would’ve been loggers; there would’ve been people out there tapping what’s called the chicozapote or sapodilla tree, in order to extract the sap that would eventually make its way into chewing gum, at that time.

Now, what we know about Lamb, Dana Lamb, is that he comes across as a blundering neophyte in this deep jungle. He clearly needed local help to get to this place where the lintels were found. They allowed him, I think, to survive. It must’ve been an exceedingly uncomfortable hike. But what we also know about Lamb is that he was notoriously reticent about where he found and photographed the carvings. And there were at least two in the ancient building that he explored back there in the spring of 1950.

So what we’re doing in the Getty book is we are probing what we’re calling the afterlife of these carvings, as well, after they’re removed from this home. And what they tell us is that these carvings were made by an identifiable, superlative sculptor whose name we know and can decipher. It was Mayuy, which is a word that refers to mist and clouds. And what they also tell us is that this sculptor introduced idiosyncratic, brilliant effects, and that he asserted his identity in ways that were not otherwise known in the corpus of Maya carvings.

And they also tell us that he was able to craft within this object a masterful political statement that aligned politics with understandings of that time of cosmos, and even of creation, and also vice versa.

CUNO: Now, you call the carved Maya stones orphaned carvings. And you write that they have an unstable relationship to time. Tell us about that.

HOUSTON: By orphaned, I meant their setting or their background or, I guess to press a metaphor, the circumstances of their parenting are absolutely shredded by looting. And for me, the task of this kind of scholarship that is exemplified in this book, we think, is to retrieve that knowledge in various ways and for various objectives. One purpose or aim is purely intellectual. And that is to find out more about the carving—who made it and why, what it might communicate more broadly about the Maya and ancient imagery more generally.

But also, as I mentioned before, that the setting truly matters—where the building was found, what that building might have presented architecturally, what might be the archaeological deposits nearby. And ultimately, we want to be able to extract information about the political, the cultural, and the aesthetic circumstances of its creation. Now, I would also say there’s a forensic objective here, too, which is sorting out who took these lintels from their home—who orphaned them, so to speak. And ultimately, should it be feasible, I think there’s an interest, potentially, in repatriation by some process, legal or otherwise. Because there really is zero doubt that this carving was taken from Guatemala when local laws prohibited such removal, whatever the international laws and regulations of that time.

But I think at least, there could be, wherever these monuments are—and one is in a very securely known location, in a museum in Texas—we want to know, or at least to recognize, where they came from, so that that can be advertised and specified very precisely, because I do think transparency and honesty about these things are virtues, and that we can employ knowledge in their service.

Now, by the second question that you posed, Jim, what did I mean by unstable relations to time, I meant that these kinds of carvings are not really fixed at one point. And I even use this analogy of trying to date a boat simply by when a champagne bottle was broken on its prow at the time of launching. And in fact, we know these limestones are literally millions of years old. Then there was the time of quarrying, in which the limestone is taken out of a stone bed. There would be events taking place that would be eventually recorded on this monument.

There would be a carving, there would be an act of erection or emplacement. And then often, these kinds of carvings among the Maya are either ritually deactivated or they might be destroyed by enemies. And then later on, there’s an afterlife that would include—and there’s the kind of lithic biography—visits by local later Maya, who would burn incense near or on these monuments. And then eventually, there is the act and process of looting itself, by which these carvings are traveling around the world by boat or jet. And that story is not an end at all, and hopefully, it will continue for some time to come. And so these monuments are, to me anyway, notionally in a kind of slipstream of time. And that will never, never end.

Now the other thing that, to me, is fascinating about even considering the problem of time, the way we might conceptualize it with respect to this carving, is that the carving itself, as we studied it, tends to prefigure later carvings by this very same sculptor, so there’s a rich oeuvre, we know, of his work over a ten-year span. We know, for instance, he’s coming from an enemy dynasty. He’s a bit of a turncoat. He’s probably looking for a more lucrative position here in this kingdom.

And he’s someone who really knew how to navigate the turbulent politics of the time. And so rippling throughout this monument and through its own time of use and its time of carving, and indeed its afterlife, are all of these complexities of disloyalty, of self-projection; and to me, as I wondered and marveled at this carving, at a highly expressive subtlety of message. And it’s playing out in his full body of work.

CUNO: Now, that’s extremely interesting. On what basis can you determine that there is a corpus of works by the same single sculptor? Is it just the appearance, that it seemed to be so much similar one to another? Or what else would there be?

HOUSTON: We’re blessed, in the Maya evidence, to have many, many named carvers and also calligraphers.

CUNO: The name carved into stone?

HOUSTON: That’s right. So at the moment, I have documented at least about 130 named carvers. And that’s coming very close to the number of artists we might know, let’s say, in Classical Athens. And there were probably about twenty to twenty-five, depending on how you understand the evidence, named calligraphers.

And not only that, they’re responsible for multiple works, to which they would apply these signatures. And this is something we’ve known about for some time, but it’s only recently being documented to a fuller extent. And it is opening up all sorts of exciting possibilities of interpretation.

The language of the inscriptions is not necessarily always reflecting the local speech. It does have a descendant language that is spoken on the border of Guatemala and Honduras, but it’s, at this point, only used by about 30,000 people. And this came as something of a controversy in my field because everyone had assumed there was a local expression of whatever language might be spoken at that time.

But instead, we’re getting this strong feeling of what linguists technically would call diglossia, in which there is a profound linguistic, or again, expressive abyss, almost, that exists between what the rulers are saying and what they’re recording in the inscriptions and what people out in farm and field might be speaking, as well. So it is above all, a very acutely hierarchical society, and language became, I think, part of the equipment they employed to accentuate those differences.

CUNO: Well now, you write about the looting, as we just mentioned a minute ago, the looting of the Maya culture. And you say that it thrives in conditions of relative stability. What do you mean by that?

HOUSTON: There isn’t a Maya ruin I’ve ever visited— And I’ve visited literally hundreds, if not thousands, at this point, including ones that are often under heavy guard. But each one of them is intensively looted. They’re like Swiss cheese, Jim. And this is a process that really, really intensified in the sixties and seventies, and even beyond.

And I was being, I think, a little audacious in that statement I just made about stability, because obviously, looting does thrive in conditions of instability.

But in Guatemala, in the place particularly where this lintel comes from, looting was actually suppressed by the conflicts between the guerillas and the Guatemalan army from a period of about 1997 and about fifteen years before. The reason for this is pretty obvious to me. Which is the guerillas not only had this commendable ethos of protecting ruins, they were committed to an ideological perspective about patrimony in the country; but really for a practical reason, they did not want looters padding through the forest in ways that might potentially report on the location of guerilla combatants, and then pass on that information to the military.

And so in many ways, the worst looting in Guatemala actually took place also, I would say, prior to that terrible civil war in that country. The civil war tended to suppress it; it tended to stop the more brazen acts of criminality. Why did the looting take place? It took place because this area, which had been almost unimaginably remote until the sixties, suddenly experienced an influx of people coming from other parts of Guatemala; individuals and families being forced out of land by oligarchs or by a land grab by a few very wealthy people up in the highlands of Guatemala.

And at the same time, concurrently, there was, I would also say, a mounting or growing interest, in places like New York City or in Europe, in what was then called primitive art, a term, of course, we eschew completely at this point.

CUNO: You write about the historical practice of partage. Tell us what partage means in principle and what it means in practice.

HOUSTON: It’s a term that comes from the ancient world, particularly in Egypt, in which many objects flowed out to museums. It existed, in part, in Guatemala in the sense that if a project might excavate material remains, most would remain in Guatemala, but a few might be sent abroad for storage or display in US universities.

Piedras Negras, where I excavated quite a bit in the nineties, is a good example of this, in which half the ceramics went to Philadelphia, to the University of Pennsylvania Museum; and the remainder stayed there in Guatemala City. Belize has also had, traditionally, this system, especially, I would say, in the sixties, in which there really were not adequate storage facilities or places to display objects in Belize in that period.

And so many of them went to, of all places, Canada, which was, of course, part of the British Empire as well, until fairly recently. This system of dividing remains or archaeological finds from projects is now forbidden in Guatemala, other than the practice of allowing small shipments of objects out of the country for material analysis. And I personally think—this is my own perspective—that for study purposes, small collections of pot shards and animals bones can still be responsibly stored and researched abroad.

CUNO: Well, let’s turn now to the particular lintel stone— We mentioned the name of Dana Lamb. But tell us who Dana and Ginger Lamb were and why they feature so prominently in your book.

HOUSTON: They were a couple from California who first undertook, in the thirties, a canoe trip from their state all the way down to Panama.

CUNO: A canoe trip?

HOUSTON: Yeah, canoe trip.

CUNO: From California to Panama?

HOUSTON: That’s right. Not a conventional way of getting from one place to the other. But the intent was to have a grand adventure. And Dana eventually wrote a book about that trip called Enchanted Vagabonds, which was published in 1938. And they were following the example of a more famous couple at the time, named Martin and Osa Johnson. And Martin having been the cook on Jack London’s voyages.

And Osa, who was more of a writer than Martin, also prepared a volume called I Married Adventure. What an extraordinary title. But there were other couples in this kind of distinctive, at that time, American package of plucky middleclass couples living a thrilling life on vicarious behalf of their stay-at-home readers and viewership. So in all of these, what you do see is a kind of theme that threads through them, which is the stories had to be often rather desultory, like life itself. A kind of random set of collisions and experiences over time. And I’ve sometimes wondered if that had to do with an attempt to heighten their claim to authenticity.

But to get back to Dana and Ginger, who were very much building on this tradition, in this book called A Quest for the Lost City, they were doing Enchanted Vagabonds 2.0. But now Dana was interested in movie rights as well. And they probably would’ve done this trip earlier, but World War II intervened.

CUNO: Well, tell us about the book and the film, Quest for the Lost City.

HOUSTON: It was a book that was coauthored by Dana with his wife Ginger, but it was partly ghosted by a bookseller named June Cleveland. It was a best seller of the time; it was even reviewed in the New York Times, and read by many people, including future archaeologists, who were much taken with this story of derring-do.

Now, he, in this volume, decided to go look for “primitive natives”—that’s very much in quotation marks—in rawest jungle. And a good place for that would’ve been the Chiapas rainforest of Mexico, on the border between Guatemala and Mexico. The other thing to remember about Dana is that he was a very early Boy Scout and he was a committed scout master. So he must’ve been very concerned with being out in the forest, with being prepared for every possible contingency.

And also liked to indulge in himself the fun of roughing it, which must’ve been every scout’s dream. In fact, their canoe for these trips, “The Vagabunda,” is on display in the lobby of a men’s club in Los Angeles called The Adventurer’s Club. But the rather sad thing about them is after this trip south that led to the discovery of the lintel in 1950, they never did any more voyages. And the rest of their lives were leavened by little more than an occasional talk about their grand adventure to the Lost City. It’s a little bit sad, in that I’ve actually seen correspondence from Dana and Ginger, and the letterhead has the heading of “Dan and Ginger Lamb, Exploration and Motion Pictures.” But there would be only one movie called Quest for the Lost City, which was released in the 1950s and went into broad distribution.

But as we discovered, the book is full of almost laughable fabulations. At times, it’s just claptrap. It speaks about cataclysmic storms, almost a hurricane, artesian wells that are spurting like volcanoes, and so forth. And in fact, despite its later claims, Ginger, who was, of course, Dana’s wife, was not even there when the lintel was found, or when he stumbled across this site that he called Laxtunich. Just a made up name.

But Dana also wanted to do a movie. And this must’ve been in the air of the time, because of the release, in 1947, of a lot of publicity about the Kon-Tiki expedition by Thor Heyerdahl. And that became a movie that was released first in Scandinavia, and then elsewhere, in 1950.

And so Lamb’s objective was essentially to do Kon-Tiki in the Chiapan Rainforest. And he needed, probably, I would imagine, a lost city as a selling point. It would be a nice marketing twist and a climax to his story. And it would also prove to be important for his eventual producer, who was none other than Sol Lesser, with RKO. And he was well known for guiding and promoting the Tarzan movies with Johnny Weissmuller and Buster Crabbe. And he eventually produced and helped to release the Kon-Tiki movie itself in the United States.

And we know that Lamb heard about this ruin when he was in the jungle beginning this filming project. And he trekked to the site with locals. And because of documents that Lamb left behind, we have a great deal of information about what Lamb did when he got to this place. And I’ve often wondered, as have others, why didn’t he eventually fess up? Why didn’t he release more detailed information about where the lintels might’ve come from?

We don’t really know. Did it have something to do with the fact that he had another scheme afoot, a future movie in mind? Or could it be that dissimulation and mendacity had simply become a mode of life for him?

CUNO: Now, tell us about the stone itself. Describe it for us and its importance in the history of Mayan sculpture, but also, perhaps, just in sheer beauty itself.

HOUSTON: The stone itself is a depiction of four figures, and probably a mythological being, as well. The figures on top correspond to the local ruler, whose name we know, Cheleew Chan K’inich. And the other is a magnate. And down below are two other figures. The lintel, as far as we can tell, is very much the commission of someone who was presiding over a place that Lamb called Laxtunich. It’s simply a bogus term he made up. We don’t know what the ancient name of the city was.

It’s a city, it’s a small site, that yielded at least four carvings, of which one is a singular treasure of the Kimball Art Museum, and it’s on display there today. Now, what makes this lintel fascinating for us, at least in political terms, is that this monument and the other carvings that come from buildings nearby are not from the actual dynastic capital, which was called Yaxchilan, but rather they derive from a pretty small site that’s on the troubled margins of that kingdom.

And the carver that the local lord employed to create this piece, a person whose name we know, Mayuy, was almost certainly from an antagonistic dynasty to the north, a place called Piedras Negras, which is quite renowned in the history of Maya culture and civilization. We also know something about the work of this artist because we have monuments that span a period of about ten years or so. And we can understand by looking at all of these carvings, which are sometimes— which sometimes affix his signature, how he developed, what fascinated him, how he grafted, in this instance, a political arrangement between a king and a magnate-lord onto a pattern that really gets into complex iconography or imagery.

We have the ruler himself, the king of Yaxchilan, who is embodying the sun; the magnate, who’s seated by him, is representing the night and a time when maize grows. And then from the dates on the monument, we also know that they’re focusing on the equinox, on the break between the Maya dry season and the Maya wet season, a time in which things grow in very different paces.

The other thing about the lintel that intrigues us is down below, supporting these two very exalted individuals, are other people in the pecking order politically. And they are shown in the lintel as Atlantean beings who are literally supporting the sky itself, in which the king and his magnate appear. But also, as with the ruler and the magnate above, they’re identifiable in the writing, in the text nearby, as flesh-and-blood real underlings of the time.

And then the final touch, which really, really caused us great joy when we figured this out, is that the two underlings are literally also lifting the lintel itself. It’s one of these very, very few acts of self-reference that occur in Maya writing. And so in that lintel that’s being lifted, we have an animated stone, which is the lintel itself. It’s got a nose, it’s got an eye. And in its eyes, looking down at anybody glimpsing and glancing up at the lintel, are the names and titles of the carver.

And in a way, there’s a sort of studied inattention from the part of the figures on the lintel; they’re not looking at the viewer down below. Only the carver is, through his name glyphs, as it is expressed in the orbits of the lintel being lifted. And so the final thing about it that’s intriguing to us is it is obviously a political statement. It’s about supporters of the king but it’s taken into an entirely different direction. And there are lots of grounds for thinking that it’s both a specific date in historic time for the Classic Maya, but it’s also replicating overall creation, with the lifting of the sky. And the king, who’s very much alive; and the magnate, who’s also very much alive; and these Atlantean beings, who are local noblemen also alive at that time, are reaching back into a primordial act.

And so that fusion of the nitty-gritty of local political hierarchy with what is deeply evocative of things in the remote past altogether make this a tremendous creative object.

CUNO: Is there a corpus of work by this artist that is identifiable?

Yeah. There are four carvings known. Two are explicitly named as being by him. The others are in very, very similar style. And we have made, I think, a persuasive argument that the four lintels came from two separate buildings. One building was constructed a bit early; the later came about ten years after that. Almost certainly, they were found within a couple of yards of each other. And the buildings themselves are doubtless going to contain some remains of pieces left behind by the looters.

CUNO: So help us understand the topography and vegetation of the area and how consistent it is across Guatemala. What effect it might have on the physical condition of the limestone of which the Mayan stones are primarily made.

HOUSTON: This part of Guatemala, it’s highly broken in landscape. It’s like the Appalachia, you might say, the Maya region. And I think it was always, Jim, quite remote, even in the times of the Classic period. And this may, in turn, account for the kind of micro kingdoms or the political fragmentation that are illustrated or exemplified by the carving we’ve been looking at.

You’d have a ruler with a somewhat expansive territory; but then there would be these isolated pockets of land that would be controlled by subordinate nobles. And in those smaller sites and in those isolated pockets would be lintels, of which quite a few are known from this area. Not necessarily of royal commissions, but ones that are undertaken by local nobility. Today, it’s an area that’s under onslaught. It has been logged and given over to cattle farming or to intensive agriculture. But there are, in the Guatemalan side, not too far, almost certainly, from which the lintel was found, where there are more or less untouched reserves of rain forest, with forest giants like mahogany or animals like jaguar, which are long gone elsewhere.

And in this is limestone, which the carving’s made out of. And it tends to vary enormously in quality. Some of it can be super soft; it’s almost like talc powder. Other stone, however, is almost crystalline in hardness. And that would be the kind of stone from which this lintel is made.

CUNO: What about pigmentation? Are there pigments left on the stone still? And what were those pigments made of?

HOUSTON: The pigments involve a blue made of indigo that’s taken from the Anil plant. And they were then combined with a clay called palygorskite, which is found in only a few locations. It’s very, very fine. It’s a white clay. The reds we see on this are likely ferrous, and sometimes they’ll glint with little inclusions. And that tells us that it’s cinnabar, which is a very different kind of material, potentially poisonous, in fact, because it was mercury. But the pigments were cooked in such a way as to cause them to blend in a manner that could be successfully applied to the surface. The blues are symbolically important because they’re linked to jade and to other sorts of precious substances, such as the Quetzal plumes that come from this adorable bird from highland Guatemala that has a tiny body, but an immensely long set of green plumes, which were also prized by the ancient Maya.

Now, on the carvings that we studied, the blue rims of the glyphs are probably referring to the idea of preciousness. They’re almost communicating the idea that the writing is bejeweled in some ways. The red would contrast intensively with that. There were some yellows, as well, that are probably made out of some other kind of mineral. But those two colors, the last ones I mentioned, red and yellow, are themselves probably reflecting the kind of refulgent solar quality of the imagery.

Remember that the main figure is impersonating the sun god. And so these aren’t just random aesthetic choices, but the colors applied to the stone are going to be carrying a lot of different meanings that were vitally important to the Maya.

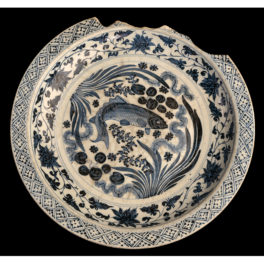

CUNO: How do they relate to painted vases of the same period, the same area? What kind of stories do the reliefs tell, and do they tell different stories than the vases tell?

HOUSTON: Well, we have a few examples of reliefs that have essentially transferred designs from pots. But in point of fact, that’s pretty unusual. There seems to be a very context-specific use of genre designs. Very different, especially in the case of carvings and painted pots. Now, the pots were used anciently, for the consumption of food and drink. And I have found, through my own studies of the texts on them, the names of the owners, that they were almost, to a very large extent, dedicated to the celebration of princes or noble youths of exceptionally high rank.

The carvings, however, are of a different sort. They tend to celebrate the completion of important periods of times. And at those moments, there would be the impersonations of gods, in which their ethereal substance would be housed in the flesh of the dancer. There would be the burning of incense. And then other ones are highly marshal, very belligerent in their imagery. And they’ll involve or project very elaborate scenes of captives being taken in battle, and also in the ensuing tribute that would come from the feet of enemies.

CUNO: Were there pots found at the same site as the lintel itself? In other words, was it that rich a visual area?

HOUSTON: The area is well endowed with carvings. It is not very well explored, for the reason that it was very dangerous to work there for quite a long time and remains quite remote. Nonetheless, there are plans afoot to try to return to this region and to explore it in more detail.

CUNO: Now, and we’ve talked a bit about the Lambs, but what about this man named Ian Graham? Why does he feature so much in your book?

HOUSTON: Ian Graham is a legendary figure in my field. He was arguably the greatest scientific explorer of the Maya in the twentieth century. And by explore, I meant someone who was not burdened by the need to stay at one site, but he visited hundreds, if not a thousand Maya ruins, doing maps and also recording inscriptions. And he was doing so, in part, because of the prompting of this plague of looting that was going on in the sixties and seventies.

He’s also quite interesting, in that he comes from that grand tradition of the English gentleman amateur, in that he had no training in archaeology, although he was trained in conservation. His undergraduate degree was in physics, of all things. But he made it his job to go out and record all of these carvings before they were looted, and to retrieve as much of their context as possible. I mentioned that he was an amateur gentleman. It’s because he was essentially self-supporting, Jim. He was a sprig of the ducal tree of the Dukes of Montrose in Scotland, so he came from a very distinguished background.

But because he had collected so much information, he continues to loom quite large, in a positive way, in my subject. And by simply compiling or collecting as much information as he did, it’s led to great advances in Maya decipherment, especially in the last three to four decades. Now, it’s also true that Laxtunich was lashing Ian, you might say. He was continually perplexed by this problem of sorting out where these lintels came from precisely. And it remained, until recently, I think, one of the great mysteries of Maya imagery, as to where these objects, which had fascinated so many scholars, might’ve come from. Ian tried hard to get to the bottom of that story, but he was never able to do so.

CUNO: So he and the Lambs and were interested in Laxtunich. How does that relate, how does that site relate to El Tunel or Bonampak?

HOUSTON: El Tunel is Laxtunich, in our opinion. Laxtunich was a name that was concocted by Lamb. He never recorded, Lamb did, any precise information about the location of the lintels. He tended to be highly unreliable in any communications.

The one scholar who heard from him on this subject in the 1950s was the doyenne of my studies, someone named Alfred Tozzer at Harvard. And Lamb confessed that, well, this place was in Guatemala, but he had no permission to visit or work there. And so it was largely concealed. And so that was extremely distressing for the field.

Now, what we were able to do, and especially Andrew Scherer, who’s my colleague who focused in this most particularly, is to go to the remaining papers that Lamb donated to the Sherman Library in Corona del Mar, down in California. And there are relatively reliable records that were never shared with anybody else, in the form of field notes or diaries, that tell us exactly how Lamb got to this site. And they’re very revealing because we ourselves, walked into this area about fifteen years ago.

And so there is, in our mind, very, very little doubt that Laxtunich, which was so vaguely specified as to location by Dana Lamb, is this place called El Tunel.

CUNO: What about Bonampak?

HOUSTON: Bonampak is a high-ranking city. It’s not as important as Yaxchilan. And indeed, for much of its existence, it was a dependency of Yaxchilan, which was the superordinate, dominant kingdom in this area. There seems to be pretty good evidence that the known carvers at Bonampak came from Yaxchilan. And I would be very surprised if the great painting at Bonampak wasn’t made, ultimately, by painters coming from Yaxchilan.

But even the coloration of the stone lintels that we’re looking as is similar to what you might see in the paintings, and also the carvings, that help to define the doorways leading into the great murals at Bonampak. So it’s part of the same world. And I would be also shocked if Mayuy, the carver that we’ve been examining, didn’t know the painters, didn’t know the carvers at Bonampak. They’re part of the same creative explosion towards the end of the eighth century AD.

CUNO: So we have three sites, if I have my numbers correct, El Tunel being one of them; Yaxchilan being another; and Bonampak being a third. What proximity do they share? How close are they to each other and how much of Guatemala are they?

HOUSTON: Yeah. Yaxchilan was, as the Laxtunich lintel tells us, in a way both figuratively and literally, the sun for the local political system. And what I mean by that is that they were all in its orbit. It was the center around which they tended to revolve.

These are all of these small communities governed by nobles, some of the petty sort, some also like magnates. And that is where a lot of these lintels come from, are these small communities that were under the thumb of Yaxchilan. Now, the sculptures from all of these communities, these smaller places like El Tunel or Laxtunich, tend to be fairly emphatic in emphasizing that almost suffocating centralized control that emanates from Yaxchilan.

Or at least it was the claim of that dynasty. And it’s almost impressive to me, in that it’s almost as though they protest too much, because this is within a couple of decades of the collapse of Maya civilization, and it could be this frenetic cultural activity has something to do, in fact, with a kind of Band-Aid or a way of disguising what could have been fracturing tensions within this kingdom.

Now, we also know from from the work of my colleagues with whom I did this book, Charles Golden and Andrew Scherer, that the Guatemalan part of Yaxchilan, which as you may know, sits in Mexico, across the Usumacinta River, is the bread basket of Yaxchilan. It’s where most of their food came from. Yaxchilan itself is in not a very prepossessing area. It’s very broken landscape. It’s not gonna support a lot of people. It’s a heavily folded topography.

And so the lintels, we think, both in this particular series, but also in all of those spread without this kingdom, tend to be very bold statements about control, at a time in which it is probably beginning to fray. And that’s what makes them really exciting to us, as well.

CUNO: Well, what’s next on this project?

HOUSTON: The next part of the project is to get back to the jungle. We’re all very busy with other projects, but it’s obvious that we’ve laid out what could potentially be a successful research program to return to this area, to excavate places like El Tunel, to recover even more of the meaning of these lintels, perhaps to find other fragments that would be left behind. And that would, I think, lead to an extremely important chapter in the final century of Classic Maya civilization.

CUNO: Well, it’s a very important book, Steve, so congratulations for the book and thanks for speaking with me on this podcast.

HOUSTON: It’s my pleasure, Jim.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman and Karen Fritsche, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003 and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

STEPHEN HOUSTON: Lamb’s objective was essentially to do Kon-Tiki in the Chiapan Rainforest. And h...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.