A gold amulet from medieval Byzantium reveals a long tradition of wearing jewelry not only for status, but also for protection from evil

Gold Chain and Amulet (detail of amulet), A.D. 600s, Byzantine, made in Lesbos, Greece. Gold. Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Imagine a world where a parent’s protection of a young child’s health depended on a prayer hidden within a piece of jewelry. Safeguarding the most vulnerable members of society through the invocation of the sacred was common practice in medieval Byzantium, where infant mortality rates have been estimated at nearly 50 percent. Even Christian parents borrowed freely from ancient pagan practices when protecting the young.

Dressing against Danger

During the Byzantine Empire, ritual adornment was one of the traditional ways to seek spiritual and physical assistance. A child’s amulet and bracelet from the Krategos Treasure, currently on exhibit at the Getty Villa in Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, provides insight into how parents defended their children from physical and spiritual dangers.

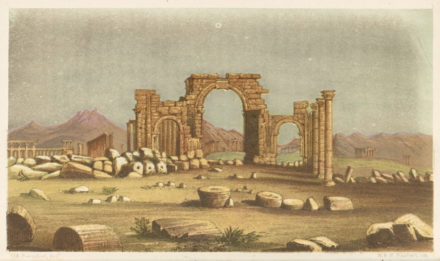

The Krategos Treasure was unearthed in 1951 during construction of the Mytilene International Airport on the Greek island of Lesbos (Mytilene) and consists of 17 silver vessels, 22 pieces of gold jewelry, and 32 coins minted in Constantinople. The hoard can be dated to the early 7th century based on numismatic evidence and imperial control stamps on the bottom of the silver vessels. Likely buried for safekeeping after A.D. 630 by residents who feared hostile invasions of the island, this cache of objects may represent the valued possessions of a single or extended family of wealthy Christians. Of the 22 pieces of jewelry in the hoard, four were amulets intended to protect the wearer from harm. Several of the amulets and a bracelet were intended for children.

The Krategos Treasure was unearthed in 1951 during construction of the Mytilene International Airport on the Greek island of Lesbos (Mytilene) and consists of 17 silver vessels, 22 pieces of gold jewelry, and 32 coins minted in Constantinople. The hoard can be dated to the early 7th century based on numismatic evidence and imperial control stamps on the bottom of the silver vessels. Likely buried for safekeeping after A.D. 630 by residents who feared hostile invasions of the island, this cache of objects may represent the valued possessions of a single or extended family of wealthy Christians. Of the 22 pieces of jewelry in the hoard, four were amulets intended to protect the wearer from harm. Several of the amulets and a bracelet were intended for children.

Bracelet, A.D. 500s–600s, Byzantine, made in Turkey. Gold, 2 1/4 in. diam. Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

The emotional resonance of the amulet and bracelet in Heaven and Earth touches even the casual viewer. Intended for a tiny wrist, the bracelet is only 2 1/4 inches (5.6 cm) in diameter, and preserves monograms at the ends of the border.

The gold amulet is cylindrical in shape, rounded at each end, and decorated with granulated bands. The hollow interior once housed a lamella (a thin silver or gold sheet with an inscription) that was rolled up and inserted into the small container. Suspended from a chain, this amulet was worn around the most vulnerable part of the body, the neck, and rested just above the heart. The secret prayer contained within the amulet was thought to avert evil spirits and guard against harm or illness. Although the Church officially condemned magic or superstitious practice, amulets worn in Byzantium were containers for prayers, whereas in the ancient world such objects were used as the objects of mediation themselves.

Gold Chain and Amulet (detail of amulet), A.D. 600s, Byzantine, made in Lesbos, Greece. Gold. Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens

Amulets to Protect the Vulnerable

It is interesting to compare this medieval amulet with works made centuries before, also on display at the Getty Villa. Exhibited in the gallery immediately adjacent to Heaven and Earth is this lifelike portrait of a young boy painted in the second century A.D. in Fayum, Egypt. He is protected by a small gold amulet encircling his neck.

Mummy Portrait of a Boy, about A.D. 150–200, Romano-Egyptian, made in Fayum, Egypt. Encaustic on wood, 8 x 5 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 78.AP.262

The boy’s direct gaze challenges the viewer to imagine his fate. This is a funeral portrait, intended to cover the child’s face in burial—indicating that the amulet failed to offer the necessary protection. The frequency with which boys, like this young Egyptian, are represented wearing amulets has suggested to some scholars that these containers were specifically intended to protect male children, at least in Egypt. Whether the same claim can be made for Byzantium remains an open question.

Also on the second floor of the Getty Villa, a small gallery contains several examples from the Getty Museum’s collection of lamellae—small, thinly hammered sheets of metal bearing inscriptions that invoke the spirits of protection. Such lamellae are found among many cultures, including Jewish, Syrian, and Greek.

Gold Lamella, A.D. 200s, Roman. Gold, 1 5/16 x 2 1/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 80.AM.53

One third-century lamella of the type that might have been enclosed in the Byzantine amulet is inscribed with a Greek incantation protecting against epilepsy.

Averting Evil?

All these objects exemplify the ancient tradition of wearing jewelry both to display status and to protect against danger. Harnessing protection for the health of children was critical to both ancient and Byzantine culture. By using objects with apotropaic power—the ability to avert evil—Christians appropriated practices that had existed for centuries.

We live in a time in which the effectiveness of childhood vaccinations is hotly debated. Contemplating the beautifully formed amulet in Heaven and Earth, we might pause to consider the fact that Byzantium’s main course of action in protecting children from harmful disease was frequently the intercession of otherworldly powers through prayers—whether recited or worn around the neck.

A special thank-you to Maria Parani, University of Cyprus, History and Archaeology (Archaeological Research Unit) for inspiring this post.

_______

Further Reading

Henry Maguire, Byzantine Magic (Washington, DC, 1999; repr. 2009)

Text of this post © Tiffany Payne Malkin. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.