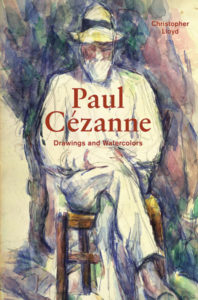

Still Life with Blue Pot, 1900–06, Paul Cézanne. Watercolor over graphite, 18 15/16 x 24 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.GC.221. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Paul Cézanne changed the course of European art forever. He altered both the way we look at the world and the way we record it.

The evidence for this lies not just in his paintings, but also in his works on paper, and particularly the watercolors. From the start of his career Cézanne was a compulsive draftsman, filling numerous sketchbooks with studies made mainly in pencil but sometimes in conjunction with watercolor. These drawings reveal the private side of a complicated artist totally dedicated to his vocation.

Slowly, during the 1880s, watercolor became Cézanne’s preferred medium. He used it to pursue motifs—landscape, bathing scenes, portraits, still lifes—in parallel with his paintings. Only toward the end of his life, when his reputation began to be established among fellow artists, collectors, and dealers, did he make watercolors as independent works of art. These works reveal unusual powers of visual analysis and sensitivity of touch, as well as a mastery of technique that has never been surpassed.

Cézanne’s numerous watercolors of Mont Sainte-Victoire close to Aix-en-Provence show his allegiance to the landscape of his birthplace in the south of France, and those of male and female bathers demonstrate his adherence to the classical tradition. But it is in the still lifes that his true essence is revealed. Those dating from his final years were executed at several sittings in his studio at Les Lauves just on the outskirts of Aix-en-Provence, where he kept a limited selection of props just for the purpose.

Still Life with Blue Pot, in the Getty Museum’s collection, is one of the finest examples of Cézanne’s more elaborate, almost baroque, compositions rendered with a complete mastery of the medium. The steep, somewhat oblique, viewpoint with the table seen slightly from above, combined with the close-up effect of the items on display, is at first disorienting. Arranged precariously, the objects on the table often teeter uncertainly as though they might roll off at any moment. The overall treatment is almost eccentric: objects are distributed arbitrarily, and textures are depicted daringly in watercolor, a more liquid, diaphanous medium than thick oil paint. Given such a level of skill, it is not surprising to discover that Cézanne painted more still lifes in watercolor than in oil.

The miracle of these late still lifes by Cézanne is the way in which the personal becomes universal. The spatial disjunctions, the interplay between lines, the oscillation between forms dependent on light, the jostling of the colors and the reification (almost deification) of mundane objects create an image of almost transcendental significance.

One of his early admirers, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, wrote that Cézanne aimed to discover “the inexhaustible nature within by seriously and conscientiously studying her manifold presence on the outside.” Cézanne’s art, therefore, was essentially an analytical exercise conducted for the purpose of comprehending and representing the world as he saw it. He searched for the most convincing and honest method of recording his sensations before nature, but at the same time he was conscious of the struggle involved in this process, and ultimately felt himself to be a failure.

One of his early admirers, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, wrote that Cézanne aimed to discover “the inexhaustible nature within by seriously and conscientiously studying her manifold presence on the outside.” Cézanne’s art, therefore, was essentially an analytical exercise conducted for the purpose of comprehending and representing the world as he saw it. He searched for the most convincing and honest method of recording his sensations before nature, but at the same time he was conscious of the struggle involved in this process, and ultimately felt himself to be a failure.

Essentially, Cézanne raised more problems than he personally could solve. But it is his identification of those problems and his determination to overcome them that accounts for the veneration in which he is still held today.

_______

Read more from Christopher Lloyd in his book Paul Cézanne: Drawings and Watercolors from Getty Publications.

Text of this post © Christopher Lloyd. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.