Orestes, Elektra and Hermes at the tomb of Agamemnon. Side A of a lucanian red-figure pelike, ca. 380–370 BC. Courtesy of Wikipedia.org

Elektra’s Story

To understand Elektra (also known as Electra), daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, you need to know that her family is cursed. Her story is tragic.

Elektra’s father is Agamemnon and her mother is Clytemnestra. She has a brother, Orestes, and a sister, Iphigenia. After war and betrayal, Orestes, with Elektra’s urging, kills their mother. But, as in all Greek tragedy, right and wrong are complicated.

Agamemnon, Elektra’s father, goes to fight in the Trojan war. While he’s away, her mom, Clytemnestra takes a lover, and the two of them usurp the power of the throne. Elektra is furious with her mom.

When her dad finally comes home from war, he brings a mistress, the Trojan princess Cassandra. Clytemnestra lures Agamemnon into a bath, and kills him.

But even this is complicated. Clytemnestra has harbored a hatred of Agamemnon since he sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to ensure the winds would favor their boats to sail to Troy. In the “Elektra” plays, Elektra is more devoted to her father, and is devastated by his death.

To get her away from the palace, Elektra is married off (again, by her mom) to a shepherd so that her children will not be royal. In Sophokles’ version of the story, Elektra believes her brother Orestes to be dead, and some vase-paintings show her holding the urn in mourning.

Eventually, Elektra and Orestes are reunited at their father’s grave where they plot the killing of their own mother and her lover, Aegisthus.

“It’s very clear in the plays that Orestes strikes the blow, but Elektra is right behind him, urging him on,” says Getty antiquities curator Mary Louise Hart. “Words were her weapon. She was fierce.”

The amphora above shows Orestes about to slay Clytemnestra. Paestan Red-Figure Neck Amphora, about 340 BC, attributed as close to Asteas, Greek (Paestan), made in Paestum, South Italy. Terracotta, 18 3/4 × 7 13/16 in. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Was She Real?

The earliest Greek language records her family, so Elektra has been around “for as long as the Greek’s have been writing,” says Hart. Her family is one of the major families of Greek epics.

Elektra became immortalized through Libation Bearers, the second play of The Oresteia by Aeschylus. The trilogy was first put on stage in 458 BC at the Festival of Dionysos, an annual cultural and religious celebration in Athens.

“Aeschylus was the most revered of all playwrights by the Athenians. And we know that from literary sources—even mention of him in other plays—and also because he was the first playwright to have his plays re-performed in theaters across Greece,” says Hart.

Greek tragedies were always performed as trilogies, each one around 60-90 minutes, followed by a shorter play, called a Satyr play, which presented a darkly comedic vision of mythical plots.

During the festival, three separate playwrights would show their plays (one on each of three days) and all the male citizens of Athens would vote to determine the winner. The Oresteia won in 458 BC.

Later, Sophokles and Euripides both wrote plays called Elektra, perhaps around 413 BC.

Who Has Played Elektra?

Elektra is a great character to play. “She is seen to be a Greek model. There wasn’t such thing as a female hero, but there were a lot of really strong powerful female women and Elektra is one of them,” says Hart.

She has been portrayed many, many times. But under Sophokles’ direction, a very famous actor named Polos became known for playing Elektra. To fully encompass Elektra’s pain while she mistakenly mourns her brother, Polos famously carried around an urn holding his own son’s ashes.

Around 180 AD, Aulus Gellius wrote about the Sophokles play:

There was a very famous actor in Greece who excelled in the brilliance and charm of his voice and gestures. They say his name was Polos. He performed the tragedies of great poets with ingenuity and dedication. This Polos lost his son, whom he loved exceedingly. When he felt he had his fill of mourning, he returned to his artistic endeavors. At the time, he was to act the Electra of Sophokles at Athens and was supposed to carry an urn as if it held Orestes’ remains, The tragedy’s plot has Electra carrying what she thinks are the remains of her brother and mourning and lamenting his supposed death. Polos therefore, dressed in the somber robe of Electra, took his son’s urn from the grave and, embracing it as the urn of Orestes, filled everything about him not with representations and imitations, but with real living grief and lamentation. The audience was deeply moved to see the play acted this way. (Excerpted from Csapo, E. and W. Slater’s The Context of Ancient Drama, p. 264.)

The performers were all citizens, and as young male citizens, many men—even the famous politician Perikles—performed. Keep in mind that all characters were played by men, and during the Classical period (5th century) only men were allowed to watch the plays.

What Was Elektra Like?

Devastated by her father’s death, she was a wild and empathetic character. She wasn’t civilized in a soft, feminine, graceful way because she was consumed with anger and revenge. For her, there was no relief from her rage.

She’s often portrayed with short hair, which would have been cut as part of her mourning of her father. She lived in poverty and wore rags.

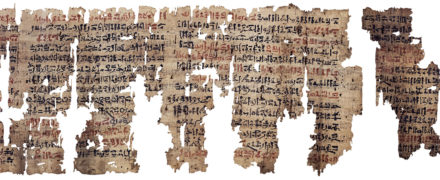

While there are many representations of Orestes in ancient art (Euripides wrote a popular play about him), there aren’t many visual representations of Elektra. However, when she is shown it’s usually mourning at her father’s grave, where she meets Orestes and they plot to murder Clytemnestra.

How Was The Oresteia Preserved?

Less than 10% of the original Greek plays have survived. It is thought that many plays were lost when the Great Library of Alexandria burned in 48 BC. What has survived is thanks to the diligence of Byzantine monks and scribes who copied them in manuscript form for their poetic heritage and quality, and also to teach Greek. “We owe Byzantine Greek teachers a huge debt for the preservation and transmission of Greek literature,” says Hart.

Are There Modern Productions?

Yes! Cowboy Elektra is coming to the Getty Villa in January.

However, going back to the 1960s, Greek movie star Irene Papas played Elektra in Electra, the film by Greek director Michael Cacoyannis. “It’s one of her greatest roles,” says Hart.

Another great, contemporary take on Elektra is seen in Electricidad, a play by Luis Alfaro, that takes place in the barrios of East Los Angeles.

“The plays have many layers of meanings. Social, political, psychological and they’re just really beautifully written,” says Hart. “They’re great poetry.”

Comments on this post are now closed.