Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.

In the digital age, is art history still relevant? How can a field founded on the close study of physical objects make use of digital tools? What exactly is the emerging field of “digital art history,” and why does it matter?

These are a few of the questions we’re tackling this week at a small, three-day lab that will bring together an international group of practitioners to discuss digital art history. We’ll be sharing our deliberations throughout the week on Getty Voices, and incorporating your voice through questions and observations shared with us on Facebook and Twitter (hashtag: #digitalhumanities).

With my colleagues Susan Edwards and Anne Helmreich, we’re kicking off the week with a Google+ Hangout on Air “Resuscitating Art History.”

The discussion is needed, and needed now. If art history is to remain relevant—if it is to survive and thrive as an academic discipline—we must learn how to use new tools and methods for conducting research and sharing knowledge. Yet the field has been relatively slow to embrace digital technology, especially compared to the sciences and literary studies. The number of digital art history projects and reference sources, like ARTstor and Grove Art Online, is on the rise, but there are still many obstacles to progress: lack of resources (human, technical, and financial), lack of institutional infrastructure, and the complexities of image rights, to name just a few.

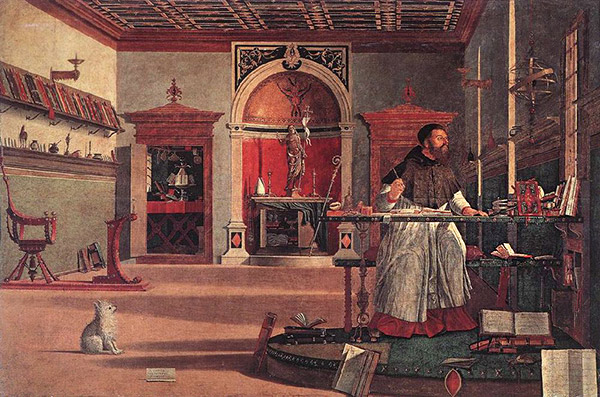

Underlying these logistical obstacles, though, are two deeper barriers preventing digital technology from becoming an essential tool for research and publication in the field of art history. The first is psychological. I call it “Saint Augustine Syndrome”—the tradition of the scholar toiling in isolation, which has prevailed in our profession from the beginning. This paradigm simply will not work in the digital world, where collaboration and interdisciplinarity are crucial.

The lone scholar toils in beautiful isolation: Saint Augustine in His Study, 1502, Vittore Carpaccio. Tempera on panel, 56 in × 83 in. (141 cm × 210 cm). Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice

The second is organizational. In most art history academic departments and research centers, digital projects do not “count” as publications, and therefore don’t contribute significantly to a professor or researcher’s professional advancement. Why do something new—something that may involve experiment and risk, extensive time and collaboration, and the acquisition of new skills—if it won’t be recognized?

These are some of the issues that we’ll be discussing during our three days together. The group for this lab is small: about two dozen art historians, researchers, librarians, technologists, students, and others, with some Getty colleagues floating in and out. No talking heads or endless PowerPoint presentations here; rather, participants will briefly demonstrate projects, and the group will discuss challenges and real-life solutions in creating high-quality, sustainable digital projects in the field of art history. We’ll ask fundamental questions that are also practical ones: What is a digital publication, for example, and should digital publications be catalogued like books?

Discussions will also touch on major areas where art history and digital technology meet:

- Data Curation. Collecting and analyzing data is a key component of digital art history. How do we “curate” data in a meaningful way?

- Old vs. New. Is the marriage of art history and information technology a happy one? If not, how can we make it so?

- Digital Resources. What’s holding us back from creating more digital resources to study art?

- Big Data. How can “big data”—the compiling and analysis of vast data-sets to perform statistical analysis and other calculations—be harnessed to serve art history?

- Access. What barriers do we face in providing wider access to digital content, such as digitized images, in art history?

Our guides and respondents throughout the meeting will be Johanna Drucker, a leading figure in digital humanities, and Diane Zorich, author of the groundbreaking study Transitioning to a Digital World: Art History, its Research Centers, and Digital Scholarship. And I’m happy to report that my old friend Max Marmor, president of the Kress Foundation, which generously provided matching funds to support the workshop, will also be in attendance.

Art history matters because art matters. I believe that art is—or should be—relevant. A recurring theme in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past (one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, and one of the most important books in my life) is that art enhances every aspect of human life. It makes reality more “real,” more intense, more meaningful. Art can help us understand the present, and the past. Digital technology, when used thoughtfully in a close collaboration among scholars and technologists, holds the promise of making art, and art-historical knowledge, more broadly available and accessible than ever before. In short, it holds the promise of making our lives more real, intense, and meaningful.

I’m very much looking forward to exploring both philosophical questions and practical issues with the group of bright, innovative scholars and technologists—including established professionals and young participants who are at the beginning of their academic and professional lives—who will be meeting at the Getty this week. Stay tuned.

Update—Art historian and participant in this week’s Digital Art History Lab, Nuria Rodríguez Ortega shares a response to this post and offers a call to action to rethink art history and its new meaning in the digital landscape here.

Connect with more “Rethinking Art History” content from Getty Voices:

- Nuria Rodriguez Ortega responds to this post with a call to action.

- Francesca Albrezzi of the Getty Research Institute describes the challenges of Digital Mellini, the first of three projects for the Getty Scholars’ Workspace

- Five participants of the Digital Art History Lab held at the Getty Mar. 5-7, 2013 discuss what digital art history could be in Google Hangout form.

This sounds like an important initiative. We need to create an open community of interested parties and avoid the St. Augustine syndrome you warned against. The recent THATCamp CAA sought to do that by bringing together numerous communities and by linking to leading projects. We should not keep such projects separate—we need to work together. Here is the website for the CAA THATCamp: in case some of your readers are interested.

Steven, thanks for your comment. In fact, THATCamp@CAA, which I attended a few weeks ago in NY, gave me a lot of good ideas for this lab. And you are right–we need to work together! Murtha

Congratulations! I wish we were as far advanced here in Europe with ideas like this. It really is a question of survival, and we should not omit mentioning this facing all those who think that we can always go on as we did before.

Hubertus, you are so right. In fact today in the workshop it came up several times that perhaps it’s not even necessary to say “digital art history,” because this is simply the way we work today. Wish you could have been here with us.

To be continued.

Murtha

As an outsider – a retired academic from the ‘hard sciences’ – I am very much interested in what comes out from this important initiative. In my view the area “Big Data. How can “big data”—the compiling and analysis of vast data-sets to perform statistical analysis and other calculations—be harnessed to serve art history?” is the one which can help a lot to push art history effectively in the digital age. Providing retrieving systems with reliable high resolution pictures of the originals is of course useful but is not enough. There is also a need for the old kind of scholarship “making reference lists of themes, styles, etc” as complete as possible. This will allow for new quantitative approaches to art history with tools for performing statistical analysis and visual interpretations.