I’ve been struck lately by just how deeply national allegiances to certain artists run. Statistics confirm that when I write online about French artist Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, my French audience is immediately attentive. But if I write about Swiss artist Jean-Étienne Liotard, the clicks come from Britain, as well as Switzerland and the Netherlands—but not France. The artistic misunderstandings of the 18th century appear to remain alive and well.

Liotard, with all his towering genius, is seen as a unique phenomenon, as he found recognition across Europe in competition against the best artists of each country. When he achieved sudden celebrity in London, newspapers from as far away as Maryland reported on it.

Despite the exemplary standards of image reproduction today, the initial Liotard infection can only be caught from seeing the original artworks de visu—with one’s own eyes. For a first taste, the Getty Museum’s installation of Liotard pastels (October 20, 2015–April 24, 2016) offers an impressive, varied, and representative introduction to this Swiss artist.

An Opera Singer in Love

One of the most inviting pastels on display is Liotard’s delicious portrait of the opera singer Louise Jacquet (1748–52). It is the only pastel in the group that was exhibited publicly, in Paris in 1752. After her retirement, Jacquet took the portrait with her to Aix-en-Provence, where the connoisseur François Tronchin saw it in 1769.

Compared to the other portraits in the installation, Louise Jacquet is conventional; she alone looks at us directly. Her cape is decorated with an Ottoman floral motif found in a number of Liotard portraits. Did it come from the artist’s box of accessories? The letter in front of Jacquet hints at a possible love story. Unlike his great rival, Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, who titled a contemporaneous composition Élisabeth Ferrand Meditating on Newton (1752), Liotard left it up to us to imagine a possible paramour.

Portrait of Mademoiselle Louis Jacquet, 1748-52, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Pastel, 23 1/2 x 17 3/4 in. Private collection. Photo © Sotheby’s/Art Digital Studio

A Girl and Her Dog

Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone (1755–56) was the first 18th-century pastel acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum, and it deftly illustrates Liotard’s naturalism, which was revolutionary in its time. While it was commonplace to include pet animals in children’s portraits, the children themselves were often highly stylized, as exemplified by the Portrait of Marie-Anne Huquier (1747) by Liotard’s other great rival, Jean-Baptiste Perronneau.

In his writings, Liotard expressed his aversion to leaving visible strokes on the surface of an artwork, and this ravishing example is as close to this ideal the artist ever came. Liotard included a double date—“1755 & 1756”—suggesting that Maria had perceptibly aged between sittings. Despite the cool tones of the girl’s winter outfit, her skin has a human warmth that draws us into her world.

Portrait of Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone at Seven Years of Age, 1755–56, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Pastel on vellum, 21 5/8 x 17 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.PC.273

Experimental Impulse

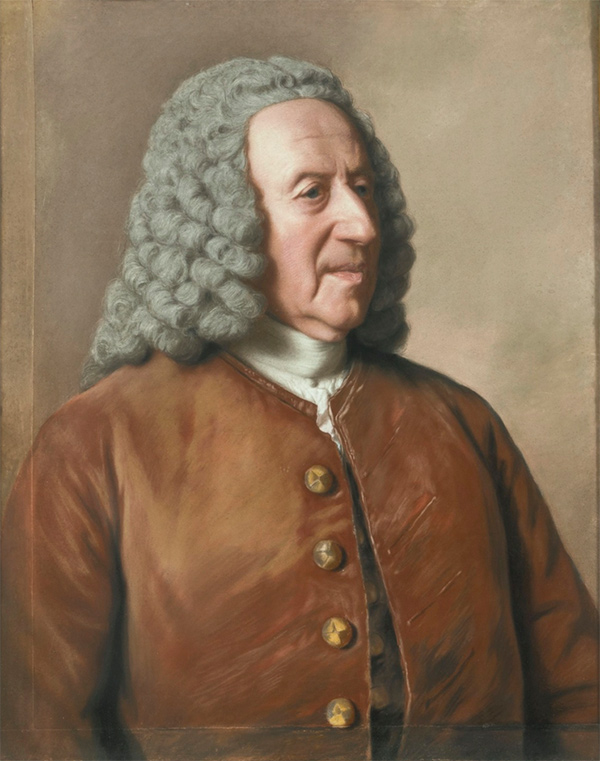

The portrait of Jean Tronchin (1759), who was an eminent statesman in the Swiss Republic and the uncle of the connoisseur François Tronchin, shows a different side of Liotard. Although he maintained his commitment to an unflinching rendering of nature, Liotard experimented with the space around Tronchin’s head by adding strips of paper to the borders. These strips are as vocal as the bars of silence in a great musical composition. Interestingly, an earlier portrait of Tronchin’s wife, Anne Molènes (1758), was the first Liotard pastel to enter the collection of the Louvre in 1982.

Portrait of Jean Tronchin, 1759, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Pastel, 65 by 52 cm. Private collection. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s

It’s All in the Feet

Lord Mountstuart, the heir to the Earl of Bute, spent several years in Switzerland, where Liotard executed a monumental pastel portrait of him in 1763. A version of this portrait showing only Mountstuart’s head and shoulders is still in the family’s collection and is featured in the upcoming Liotard exhibition at the Royal Academy in London.

In a full-length portrait, known in France as a portrait en pied, the feet tell the story. The vocabulary of feet dates back to Hyacinthe Rigaud’s famous Baroque portrait of Louis XIV (1701) in which the king stands in the fourth position of ballet, an homage to Louis’s personal skills as a dancer. Years later, in 1758, the Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay depicted the Earl of Bute— Mountstuart’s father—and added a Rococo lightness by lifting one heel in a portrait that would otherwise be as heavy as Bute’s robes. How could the earl’s son compete?

Portrait of John, Lord Mountstuart, later 4th Earl and 1st Marquess of Bute (detail), 1763, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Pastel on parchment, 45 1/4 x 35 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000.58

For Lord Mountstuart, Liotard rendered the young man in a similar posture, but turned elegance into nonchalance by placing his elbow on a mantelpiece and replacing the stately pillars with the intimacy of a Chinese screen. The mirror provides another clue to his personality; describing Mountstuart, a mutual friend once wrote to James Boswell, he “loved to look at himself, like another Narcissus.”

Good morning, Never heard of the paper along the frame in a painting used by the artist Liotard. Getty is still the best of museums, I look at many, but the little extras and joys in searching these mystery styles of artists’ rendering their work an extra helping? Did the paper along the frame emphasize the work’s prime perspective the human portrait and stance? I believe that is unusual?