Jean-Albert Glatigny participates in a panel conservation at the National Museum in Stockholm. Photo © Anna Danielsson

The Getty Foundation created the Panel Paintings Initiative to ensure that a sufficient number of well-trained conservators will be able to maintain quality care of panel paintings once the current leaders retire. Grants have concentrated on intensive side-by-side training projects, workshops, and the translation and online publication of a limited number of important historical texts related to the field. —Ed.

Jean-Albert Glatigny describes working with his hands as the apogee of life. It’s how he attains his highest sense of fulfillment and purpose. Trained as a cabinetmaker, he has spent decades sanding, hewing, gluing, wrestling, studying, splintering, and grafting wood. Wood that is constructed to form spectacular altarpieces that hang in European cathedrals. Wood that supports masterful oil and tempera paintings displayed throughout museums worldwide. Wood such as poplar, oak, spruce, walnut, and chestnut.

“I felt the most affinity for it,” says Glatigny, conservator at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels. “It was a material that pleased me altogether: the smell, the warmth, and the softness all reminded me of building treehouses!”

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (The Ghent Altarpiece), Hubert and Jan van Eyck. Image courtesy Cathedral of Saint Bavo © Lukas – Art in Flanders

Glatigny, as well as George Bisacca, Ciro Castelli, José de la Fuente, Ray Marchant, Mauro Parri, and Andrea Santacesaria, are among the dozen or so people worldwide considered to be experts in the conservation of panel paintings (paintings on wooden supports). Though some of the world’s most precious artworks are panel paintings, the number of conservators skilled enough to treat them has dwindled, failing to keep pace with conservation needs and the retirement of the most adroit professionals.

In 2008, the Getty Foundation launched the Panel Paintings Initiative (PPI) to address the field’s perilous state and ensure the training of a new corps of conservators. The experts mentioned above, as well as Roberto Buda, Salvatore Meccio, and Roberto Saccuman, signed on as trainers. Over the course of six years, these professionals convened to discuss best practices and provide individual and group training to a cohort of early- to mid-career conservators at renowned museums and conservation studios in Spain, England, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Austria, and the United States. Younger trainees were able to get first-hand experience in the conservation of European masterpieces by watching and working alongside these experts on challenging treatments.

This spirit of cooperation marked a shift in the sharing of conservation techniques. “Traditionally, workshops have guarded their secrets closely, with little collaboration among professionals,” says Antoine Wilmering, senior program officer at the Getty Foundation and manager of the initiative. “But this was not the case with the panel paintings experts, who came from different institutions yet embraced the opportunity to share knowledge—not only with younger conservators, but also with each other. Their openness has ensured that the world’s most revered old master paintings will receive the best possible care.”

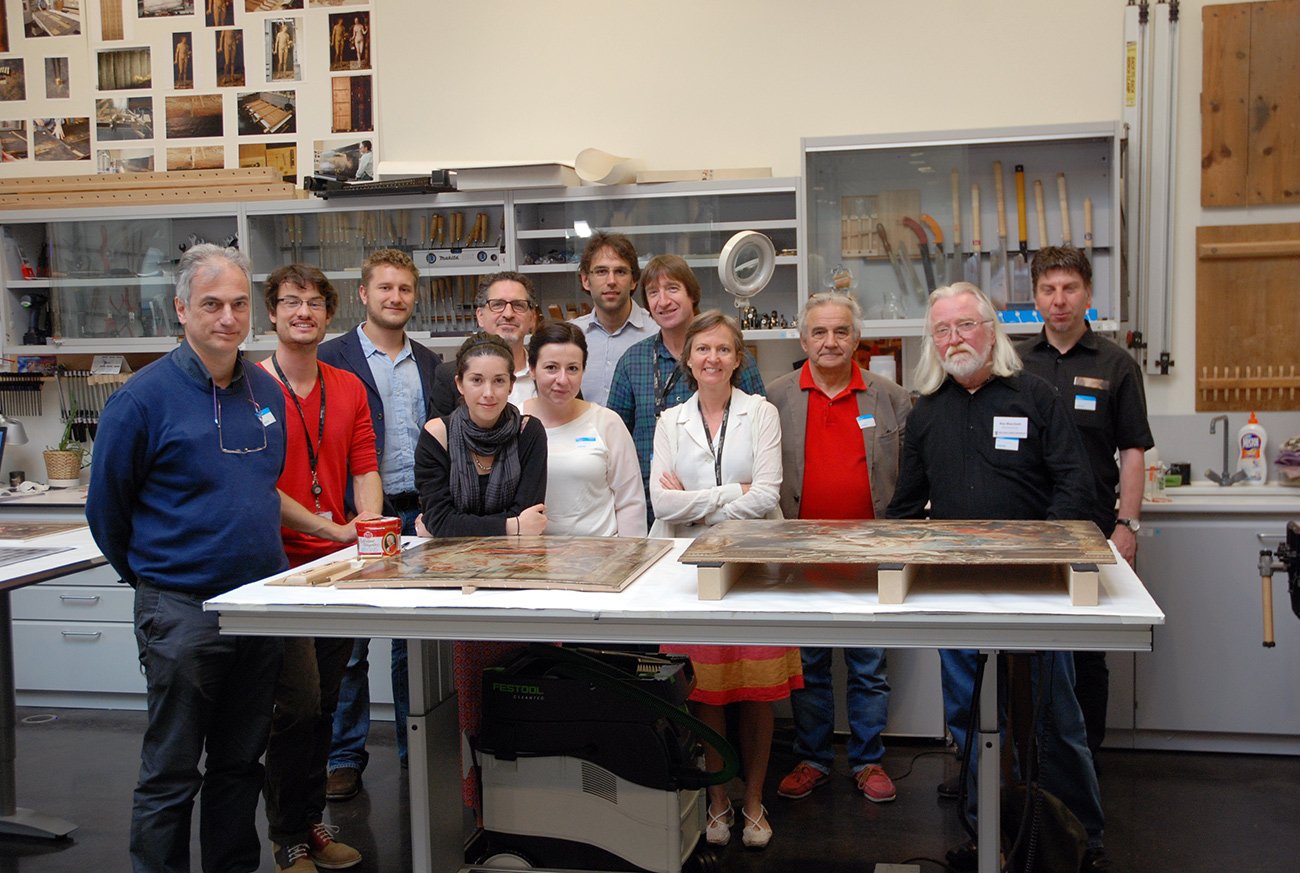

Trainers and trainees at the Prado Museum conservation studio in 2013 for a Panel Paintings Initiative convening.

The experts themselves found the new transparency refreshing. “For the first time, we were able to convene, exchange ideas, and collaborate on important restoration work,” says Andrea Santacesaria, an advanced conservator at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD) restoration laboratory in Florence.

Glatigny feels similarly. “We have traveled, met many people, and explained to our own colleagues why we have adopted certain working methods. And, the next generation has been able to network and participate in these events.”

Such exchanges mean that woodworking techniques traditionally used in Italy are seeing increased adoption in Belgium, that treatments with historical roots in Madrid are increasingly popular in London, and vice versa. And this knowledge-sharing hasn’t just benefitted trainers and trainees, it has also benefitted artworks.

As part of a 2010 effort led by Ciro Castelli, retired conservator at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Giorgio Vasari’s monumental panel painting Last Supper (1546) was pulled from storage to finally undergo treatment. It had been severely damaged 50 years earlier in a devastating Florence flood and for half a century had been considered beyond repair. However, contemporary collaboration among conservators, plus advanced technologies and techniques, helped caretakers realize that they finally possessed the expertise to bring the painting back to life.

View of Giorgio Vasari’s Last Supper (1546), during restoration at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD)

In addition to Last Supper, the Panel Paintings Initiative has allowed for the restoration of some of the most highly visible masterpieces in the history of Western art, including Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432), Albrecht Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1507), and all nine paintings by Pieter Breughel the Elder at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, including Hunters in the Snow (1565).

Because the works being restored were of such significance, these projects served as valuable apprenticeships for trainees who learned necessary hand-skills, aesthetic judgment, and technical methods from seasoned mentors.

According to George Bisacca, conservator emeritus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an apprenticeship is an invaluable experience. It starts with a fundamental understanding of materials and their working properties, helping trainees form a strong base on which to stand as fully competent conservators. And, says Bisacca while recalling his own training, successful apprenticeships are propelled by a student’s own commitment:

When I was training, my mentor, Renzo Turchi, was a great conservator. Incredibly skilled and extremely sensitive. But he didn’t want to assume the burden of teaching. He told me, “George, if we’re going to do this, it’s not going to be me that’s teaching you, it will have to be you that’s learning from me. It’s you that has to ask the right questions. Pay attention and observe critically. Ask what you don’t understand. And get a lot of practical experience.”

Once the trainee has gained enough foundational experience to advance to more complex operations, Bisacca explains, he or she can gradually be taught a more sophisticated understanding of the subtleties of the art object as a whole, including art-historical, aesthetic, material, theoretical, and ethical considerations.

Left: George Bisacca. Right: José de la Fuente and George Bisacca restoring The Descent from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden at the Prado Museum studio in 1991

Though apprenticeships are far less common in today’s world—their ground having been ceded to academic training programs—the experts celebrated the return of the hands-on approach. “Academia has done much to elevate the credibility of the profession by introducing science and chemistry in conjunction with art history and aesthetics,” notes Bisacca, “but [these developments] have sometimes come at the expense of the mastery of manual skills necessary to execute responsible treatments.”

Ray Marchant, a private practice conservator affiliated with the Hamilton Kerr Institute in London, agrees. “Considering that some students arrived to our workshops with basic tool skills, it is a tribute to their enthusiasm and hard work that, having learned repair techniques and support methods for even the most fragile panels, they now have a good future ahead of them.”

Technical mastery isn’t everything, however. There are soft skills related to panel paintings that must be taught. In that vein, Marchant made sure to cultivate his trainees’ sixth sense—a process he describes as “learning to listen to what the panel is telling you.” Indeed, Marchant is known for his uncanny ability to exert little pressures on (i.e., gently flex) panel paintings to locate areas of structural weakness.

“Even after a tree is felled and converted into boards it still exhibits life. By the nature of its cell structure, timber never stops moving,” says Marchant. “Past conservators thought that timber could be shackled with battens or cradles to submit it to the wishes of man and hold it flat in a frame. Panels need a degree of freedom, and controlling them too strictly usually leads to damage.”

Left: Trainer Ray Marchant and trainee Adam Pokorny using small pressure pads to make a surface refinement following the repair of The Madonna of the Burgomaster of Basel Jacob Meyer zum Hasen (copy by Bartholomäus Sarburgh after Hans Holbein the Younger) at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 2013. Right: Marchant working on a panel at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge, 1999. Photo © HKI

Understanding and showing respect for an artwork’s original material is a facet of the larger theory of “minimal intervention” embraced by modern panel painting conservators.

“The word intervention, itself, encapsulates a series of choices and operations that involve both media materials and the image,” states Castelli. “If restoration is to extend the life of an artwork, it must incorporate techniques that address that work’s problems or features.”

According to Glatigny, such interventions should “respect the original technique, keep the restoration as simple as possible, be easily reversible, and be more fragile than the original materials.”

This approach has gained traction among conservators who frequently find themselves reversing well-intentioned, but harmful, interventions from decades or even centuries ago. In one example from 2011, the Panel Paintings Initiative supported the conservation of six panels from Peter Paul Rubens’ famous Triumph of the Eucharist (1626) series. The panels had been preserved at the Prado Museum, but past structural interventions—including one where former caretakers had thinned the wood and applied restraints to flatten the panels—had caused cracks, deformations, and uneven surfaces in the wood, seriously threatening Rubens’s virtuoso brushwork.

José de la Fuente, panel conservator at the Prado, guided the Rubens restoration and used the project to train seven mid-career and post-graduate conservators. “It was a great opportunity for the trainees to look directly at the problems of these small paintings, some of which had been reinforced by glued pieces on the back,” says de la Fuente. “I was able to teach a variety of recourses for resolving numerous historical problems.”

Trainer José de la Fuente (second from right) with trainees at the Prado Museum

Since the launch of the Panel Paintings Initiative, approximately 25 trainees have advanced their conservation skills, doubling the number of the field’s capable professionals.

And according to restorers, the field is stronger than ever. “The current generation of restorers is better prepared, both technically and scientifically,” asserts Castelli. “Restorers today have received critical training on the material and immaterial values of the work, knowledge that is at the foundation of conservation.”

Left: Trainer Ciro Castelli guides a treatment of Last Supper at the Fortezza de Basso laboratories in Florence. Right: Castelli in 1966 at the Lemon House of the Boboli Gardens (where Florence’s flooded paintings were brought in 1966), screwing tiles to keep the joints between the boards and then to remove the crosspieces of Last Supper.

Also, panel painting conservation is now considered just as important as painting conservation as a whole. “The field is no longer seen as a carpentry issue,” remarks de la Fuente. “Restorers are aware of the importance of panels as an intrinsic part of the artwork. Panel painting conservators are valued as much as any other art conservator. Personally, I’m completely convinced that the Panel Paintings Initiative has played a very important role in this fact.”

While the initiative has worked to positively affect the field, no gains could have been made without the trainers. “Because of the countless hours of careful mentorship provided by Bisacca, Castelli, de la Fuente, Glatigny, Marchant, Parri, and Santacesaria, there is no longer concern about the future of panel paintings conservation,” says Wilmering. “In a spirit of collaboration, these experts have unlocked their vaults of woodworking secrets, using the power of information to strengthen the field.”

The conservators, after all, care deeply about their legacy of cultural protection.

Left: Andrea Santacesaria in the Laboratory of Sassuolo in Modena, Italy in 2012. Right: Andrea Santacesaria during the reassembly of the Matteo di Giovanni altarpiece in the Pienza Duomo in Siena, Italy, in 1998

“Being a panel paintings conservator is like traveling along with great artists such as Giotto, Leonardo, Mantegna, Blessed Angelico, and their carpenters, to know their thoughts and intentions,” says Santacesaria. “The study of the artists’ techniques and the preservation of their works is like guarding the beauty of the past to convey it to future generations.”

The Getty Foundation is grateful for everything these experts have done to prepare the field’s guardians of the future.

Thank you so much for your care and dedication.

Hope you give the same attention to furnitures.