Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983) was one of the 20th century’s foremost historians of British architecture. Even today, tourists wander through the historic squares of England aided by Pevsner’s The Buildings of England guidebooks, which remain in print with Yale University Press as the Pevsner Architectural Guides.

A new book by Pevsner—Visual Planning and the Picturesque, an unfinished manuscript that the Getty Research Institute published in 2010—sheds new light on a fascinating episode in Pevsner’s career, revealing how he influenced architecture and planning in the 1940s.

Pevsner was one of many expatriate German scholars who helped shape the physical and cultural landscape of their adopted homes. Like other academics who fled the Nazi regime for England, he pieced together visiting positions at colleges with the help of Britain’s Academic Assistance Council. He was briefly detained as an enemy alien when World War II broke out, but British colleagues arranged for his release and, ultimately, for him to assume editorship of the Architectural Review during the war—an affiliation that would last for 30 years.

Visual Planning emerged from this context. Pevsner’s publisher at the Architectural Review, Hubert de Cronin Hastings, asked him to write a book that articulated the history and theory behind Townscape, a campaign about postwar urban planning that was unfolding in the journal’s pages. The Architectural Review put forward proposals for rebuilding areas of London destroyed during the Blitz and redeveloping English cities to accommodate postwar transitions in the economy, transportation, and housing.

Bombing damage in London during World War II. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, ARC identifier 195566.

The Townscape campaign sought to influence urban planning and design, not just the architecture of individual buildings. In artist and writer Gordon Cullen’s phrase, “one building is architecture but two buildings is townscape.”

Hastings was keen to promote Townscape as a distinctively British approach to postwar rebuilding. Yet Pevsner’s manuscript reveals the campaign’s roots in continental art history and architectural scholarship. As with so much cultural material in this period, the migration of styles and ideas followed the migration of people displaced by conflict.

Pevsner traced Townscape’s roots to the 18th-century idea of the “picturesque.” In Visual Planning, he calls for planning to be done visually, with a painterly eye to a city’s overall composition. Pevsner asks us to approach blocks, neighborhoods, and skylines as compositions that juxtapose old and new, national and international.

Because Visual Planning went unpublished, works by Pevsner’s colleagues established the popular understanding of Townscape. As a campaign rather than a hard philosophical concept, Townscape has been reborn on a faster cycle than other more stable ideas. Its meaning has shifted several times since the initial Architectural Review program of the 1940s and 1950s, aligning at different stages with modernism and postmodernism, conservatism and the avant-garde. As Mathew Aitchison notes in his introduction to the book, we see Townscape’s traces both in the conservative revivalist principles of British new urbanism and in the radical urban planning ideas of works like Colin Rowe’s Collage City. Recently I interviewed Aitchison about Pevsner, the manuscript, and the curious ways that Townscape’s origins and future continue to shift.

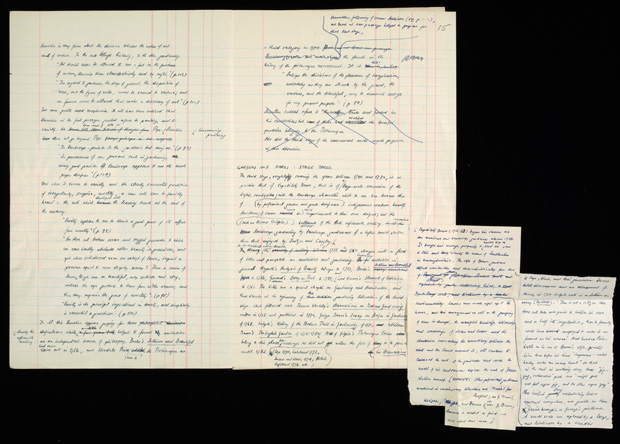

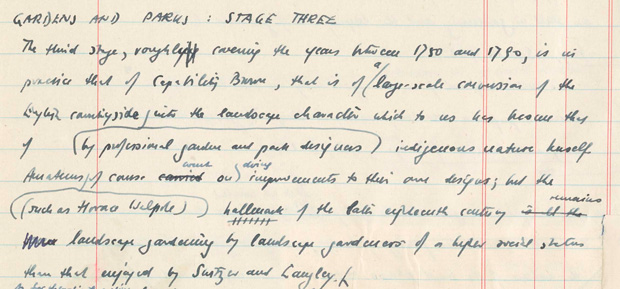

Pevsner's manuscript pages, Visual Planning, 1940s. Nikolaus Pevsner papers. The Getty Research Institute, 840209. Pevsner wrote in a minute hand on both sides of a sheet and even on small scraps of paper—a response to paper rationing that continued well after the war ended.

Despite these shifts, the questions Pevsner poses in this book remain vital: How do we rebuild after a disaster (natural or man-made)? How do we accommodate new populations and industries? How do we respect historic structures without stifling innovation? Pevsner’s Visual Planning, finally published after six decades, provides an opportunity to re-ground Townscape theoretically in a way that suggests fresh avenues for scholarship in urban planning.

Comments on this post are now closed.