Vessels and statuettes of Mercury from the Berthouville Treasure, Roman, 100 B.C.–A.D. 200, silver. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des monnaies, médailles et antiques, Paris

The present whereabouts of the Berthouville Treasure are not a mystery. In December 2011 this priceless hoard of ancient Roman artifacts discovered by chance in the French countryside over 180 years ago was temporarily transferred from its permanent home in the Cabinet des médailles of the Bibliothèque nationale de France to one of the antiquities conservation studios at the Getty Villa in Malibu.

There my colleagues Eduardo Sánchez and Susan Lansing Maish have been studying, documenting, and cleaning each of more than 100 objects—silver statuettes, cups, pitchers, bowls, and assorted fragments—as part of a collaborative conservation loan project that will culminate in an exhibition at the Villa from November 19, 2014 to May 12, 2015. You can see their reports on the work so far here.

As the curator of that exhibition, I have been researching the history of the treasure, so last month when I traveled to France for a conference I took advantage of the opportunity to visit the site where the Treasure had been unearthed.

On March 21, 1830, while plowing a recently acquired field near the village of Berthouville, a farmer appropriately named Prosper Taurin struck an ancient tile. Beneath it, in a brick-lined cist, he discovered the ancient silver hoard, which weighed an astonishing 25 kilograms (55 pounds). It had apparently been deliberately buried for safekeeping.

Fortunately, Taurin did not melt it down for its value as bullion—the sad fate of much ancient gold and silver discovered by chance—but took it to the nearby town of Bernay, in hope of a good sale. There, on the advice of a relative, he showed the hoard to Auguste Le Prévost, a learned member of the Société d’Agriculture, Sciences, Arts et Belles Lettres de l’Eure. Le Prévost quickly communicated news of the discovery to Désiré-Raoul Rochette, curator of the Cabinet des médailles et antiques of the Bibliothèque royale in Paris (now the départment des Monnaies, médailles et antiques of the Bibliothèque nationale), who promptly acquired the treasure in toto.

Berthouville is located in the Department of Eure, in Normandy, about 150 kilometers west of Paris, and on a sunny May day, I set out for Normandy with my colleague Pascale Linant de Bellefonds of the CNRS and the University of Paris Ouest Nanterre.

The town of Berthouville lies in Normandy, about 80 miles northwest of Paris

After about two hours on the highway we exited at Brionne and followed a narrow road through a forest to Saint-Cyr-de-Salerne, where, next to its 15th-century church of Saints Cyr and Juliette, we saw the first signs for Berthouville, assuring us were on the right track.

Church of Saints Cyr and Juliette at Saint-Cyr-de-Salerne, near Berthouville

A few minutes later, we entered Berthouville itself. It has a small church and several half-timbered houses. At the time of the 2008 census its population was just 287. A hunting lodge built in 1652 by Michel Morin, a gendarme of the royal guard who was knighted in 1638 and served as a councilor to kings Louis XIII and XIV, was recently restored by Boston designer Charles Spada.

Entering the town of Berthouville

The hunting lodge at Berthouville. Photo: Stanzilla, CC BY 3.0

A large notice board with photographs of the treasure offered general information about the ancient sanctuary in which it had been found, but provided no specific information about the location of the actual find spot.

The Church of Saint-Pierre at Berthouville with a sign offering general information about the ancient site

Fortunately, a friendly inhabitant, who knew that the treasure had been sent to California, directed us further down the road toward Villeret, an even smaller hamlet about a kilometer further west. There we soon encountered the “Rue du Tresor”—Treasure Street.

Me, not far from the findspot of the Berthouville Treasure

Here, amidst fields high with a crop of golden yellow canola plants, we began our attempts to correlate modern topography with the plan of the excavations conducted after Taurin’s discovery by Leon Le Métayer-Masselin of the French Archaeological Service in 1861–62 and later by Father Camille de la Croix in 1896–97. They found evidence of a multi-part Gallo-Roman sanctuary, or fanum, dedicated to Mercury Canetonensis, as well as a theater or assembly place. They also recovered numerous fragments of bronze and terracotta vessels, marbles, ivory flutes, coins, fibulae, bronze, iron, and glass jewelry, a bronze sistrum, and a fragment of a Greek inscription, all of which are today housed in the Musée d’Archéologie nationale et Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

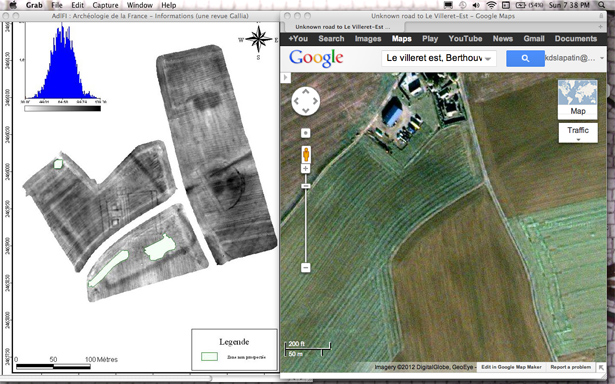

Using satellite views from Google Maps as well as recent images from geophysical investigations that employed electrical resistivity (which functions rather like ground-penetrating radar), we eventually oriented ourselves.

Father Camille de la Croix’s plan of the Gallo-Roman sanctuary from the book Le Trésor d’argenterie de Berthouville (1916). The findspot of the Treasure is marked in the peristyle at the upper right. Note the modern (19th-century) road cutting diagonally through the site.

Electrical resistivity image of the field at Villeret and a Google satellite image. The road running roughly north-south is the modern “Rue du Tresor”; the now abandoned 19th-century road runs southwest from it perpendicularly, south of the modern farmhouses.

This proved more difficult than we anticipated, as some of the old roads no longer exist, others have new names, modern buildings have been constructed on the site, and all ancient architectural features are now buried beneath the fields. But we were able to identify the site with confidence, and although the density of the modern crops precluded us from reaching the actual findspot, we did arrive within a few meters of it, which I captured in the pan below.

As we stood on the small rise on which the site was situated, we enjoyed a commanding view of the surrounding plain—a perfect location for what seems to have been a large national meeting place. For the sanctuary stood far from any individual ancient settlement, near the crossing of two major Roman roads. And we could imagine what this place looked like on the day Taurin made his extraordinary discovery, bringing to light a stunning assemblage of silver vessels that stayed hidden underground for the better part of two millennia.

Although the Treasure is now far from Berthouville, something of it remains in the area. The municipal museum of the nearby town of Bernay preserves extremely accurate replicas of ten of the finest vessels, which are stamped “Treasure of Bernay.” They were made in the 1850s by the noted Parisian silversmiths, Christofle & Company. The company still exists on the fashionable Rue Royale in Paris, not far from the Cabinet des médailles.

Nineteenth-century replicas of two cups from the Berthouville Treasure in the Bernay Museum

“Signature” of Christofle & Co. on the back of a replica silver bowl in the Bernay Museum

The replicas predate some of the unrecorded early attempts to conserve the Treasure, and they may shed some light on the original material. For that reason I have written to Christofle seeking to learn more about their commission from any documentation preserved in their files, or if, with luck, there are any surviving molds that could tell us more about the condition of the Treasure soon after its recovery. I am keeping my fingers crossed for an informative reply. Meanwhile, we anticipate additional discoveries as the conservation and exhibition project develops.

Charles Spada forwarded this on to me. Utterly fascinating, and astonishing it could have remained hidden for so long. I live on the outer edge of the Roman fort line in Perthshire, in fact the very final line of the Roman Empire’s invasion anywhere in Europe. I gather! Historians offer varying views! Next time I am in France I might well take a detour.