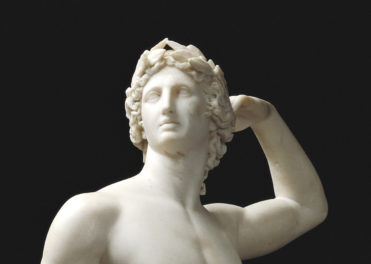

Carl “Bobo” Olson fighting Joey Maxim, April 13, 1955, American. Gelatin silver print, 7 5/8 × 9 5/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XP.880.56. Copyright status undetermined

It’s a quick moment of action frozen in time. Joey Maxim, World Light Heavyweight Champion, is being knocked to the side, his face contorted from a powerful blow. His opponent, fists raised, can only be seen in profile, making it nearly impossible for me to make out his facial features. This print is one of 534 boxing photographs in the Department of Photographs collection and it was making my job as cataloger difficult. I needed to figure out as much information about this photograph as possible, including when and where it took place, in order to fully catalog it. Joey Maxim’s career spanned nearly twenty years and over 100 fights. Without a name, I wouldn’t be able to place this print.

There were a few clues: the letter “G” mysteriously written on the back of the print, and a tattoo on the boxer’s shoulder, showing a bird above the word “Mother.” With nothing but a tattoo to go on, I channeled my inner Sherlock Holmes and got to work on the case of the mystery boxer.

The 1950s were a popular time for boxing as a number of extraordinary fighters came on the scene during the time. World War II was over. Americans, eager for a distraction, turned to TV. Anyone could tune in and watch as fighters threw punches and jabs in a flurry of fists, battling it out to be the last one standing. Clocking in at just under twenty minutes, each match was a guaranteed thrill. The era is well-documented, and I had relied on documentaries, books, score databases, and even a Russian Facebook group for boxing fans to identify previous athletes, so why not this one?

I hit only dead ends. Without a clear view of the boxer’s face, I couldn’t match him to any posted pictures. Sometimes a boxer had a distinctive logo on his shorts, like Max Baer who had a Star of David on one leg and could be identified by that. Not this fighter.

Max Baer knocking Primo Carnera to the ropes, June 14, 1934, American. Gelatin silver print, 6 9/16 × 8 9/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XP.880.470. Copyright status undetermined

However, I hadn’t seen many professional athletes from the 1950s with tattoos. I started looking into the history of mid-20th-century tattooing and landed on a tattoo appreciation website that featured a few photos of a boxer named Carl “Bobo” Olson. Feeling like a regular detective, I zoomed in on the picture of Olson and compared it to the photograph in our collection. His tattoo showed a bird over the word “Mother.” It was a match!

Finding that missing piece of information felt like watching your favorite fighter win the heavyweight championship. The tension and frustration of each setback and dead-end evaporated. The hours and days I spent researching were all worth it and I could fully catalog this print, without any what-ifs nagging at the back of my mind. The case was closed and I could move on.

As a cataloger in the Department of Photographs, I’m never quite sure what I’m going to come across. The 500 boxing prints were part of the collection of Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr., an American curator and art collector. The Getty Museum purchased Wagstaff’s collection of 26,754 objects in 1984 when the Department of Photographs was established. Wagstaff focused less on the stature of the photographer and more on what he considered to be a good picture. These prints fell into the category of “virtually unknown” and had been tucked away, untouched, in a box for more than 30 years. I was truly on my own. (In 2016 Getty exhibited 100 objects from the collection in a show titled The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs.)

According to photographs curator Paul Martineau, Wagstaff likely “admired the physical prowess” of the boxers and “respected their ability to endure pain and keep fighting.” After spending months getting to know the boxers, I do too.

Rocky Marciano fighting Ezzard Charles, 1954, American. Gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 × 7 7/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XP.880.497. Copyright status undetermined

Sorting through hundreds of boxers, I learned about the sport and started to recognize faces. Slowly these athletes of years past began to feel like old friends. “Oh, that’s Rocky Marciano and Ezzard Charles. Marciano fought Charles twice and beat him both times,” I’d tell colleagues who glanced over my shoulder.

Perhaps now, with sports at a standstill and the world seemingly on hold, it’s worth looking back at the boxers to take a moment and admire their resiliency, too.

Very well written article. I love that Jennifer went the extra mile to give us a complete history of the photos. Thank you!

(or) “…went the “extra round…”

As a fan of both boxing and the Getty, the mere thought of reviewing 500 boxing photos is thrilling. But Jennifer’s account succeeds in making it thrilling for the remaining 99% of you reading her blog. Great insight into the lengths to which a cataloger goes in pursuit of facts. And, Jennifer, in case you have come to appreciate boxing, live matches have now returned, albeit without the audience. Thanks for slugging it out in your research!

Thank you, Jennifer, for the sleuthing efforts on this remarkable boxing photo. These photos remind me of when my Grandpa used to sit right up to the little black and white tv to watch the Friday night fights! What a vivid memory of a boxing match!

You have picked a dandy pursuit of great hidden material and digested it, plus brought it forward for us to enjoy … My thanks to you —

Jennifer…the photos and description are great. I have boxing photos in my office and find there are many stories that go with each real great boxing photo. First the story of the two fighters, then the story about the fight (what makes that particular photo so interesting) and then, the story of the photographer. Thank you!

Bobo was also pretty well known in the 50s as a wrestler,as I recall. As you may know wrestling was big time on tv,esp. in LA. As a child growing up in LA with the budding media of television, I remember he was know for a head butting routine that obviously made an impression on a young boy since I still remember it. He was a boxer also of course

Enjoyed the story. What a wonderful detective job you did. You certainly are a Sherlock Holmes of Journalism.

Thanks for your sleuthing. Great pictures.

I love good research! But I wondered if you had considered the racial aspects of this period of boxing? In light of BLM I would like to know more about how boxing and the photography of boxing at that time seems to reveal great racial diversity than what was going on in daily US life. I know several scholars who write about boxing and its worlds of fans and star boxers and training, but I wondered if the photographs themselves (the bodies, the gestures, the stop action, the lighting, the choreography of stilled techniques), especially the information like the names of boxers might be especially important, as you did, to research and examine and bring forward into our current knowledges, however difficult that may be. Cheers for your discoveries. Please keep going. Let’s change history from the inside out and outside in.

best safe wishes.

PS when will Getty let researchers in the archives?

Nice article on boxers of past with some really good pics. And yes she definitely turned her detective skills to good use.

very interesting photo journalism

My Dad was a sparring partner to many famous boxers

during the depression. He received $50 for each match -It was a lot of money because

most people got $7 a week.

. My mother was in the arena volunteering to help the boxers that got hurt

My Dad got knocked out–my mother said don’t ever spar again he did not–they were

married a year later.

Great photos! I especially loved the photo of Rocky Marciano giving the great Ezzard Charles another good crack.

I would like to point out that history has not been kind to the Brockton Bomber; he is rarely mentioned as one of boxers greatest champions.

But those who saw him fight, like me, know that, pound for pound, he was one of the greatest who ever “laced ‘em up!”

It is wonderful to hear the stories behind the visual story. Keep this up! Thank you,

This is an edifying and enjoyable article to read. Thank you for sharing the research you did to bring

this amazing history of boxing to all.