The early Baroque artist Caravaggio painted bold compositions with dramatic lighting that emphasized the physical and emotional humanity of his subjects. In this episode, we listen as two curators, Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen, visit the Getty Museum’s exhibition Caravaggio: Masterpieces from the Galleria Borghese to talk about the paintings on view.

Gasparotto is senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum and Christiansen is the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is recommended to view images of the paintings online while listening.

More to Explore

Caravaggio: Masterpieces from the Galleria Borghese exhibition information

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

DAVIDE GASPAROTTO: This painting, because of the format, because of the type of composition. It became a model for generations to come.

CUNO: In this episode, curators Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen discuss three paintings by the early Baroque master Caravaggio.

The late sixteenth- and early seventeenth- century Italian artist, Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio, is among the most admired painters of any time. His blend of classical forms and emotional realism, and the passion of his subjects, transformed European painting in the early years of the Baroque era.

Recently the Getty Museum had the good fortune to have three Caravaggio masterworks on loan from the Galleria Borghese in Rome: Boy with a Basket of Fruit, Saint Jerome, and David with the Head of Goliath. These paintings reflect three different periods in the artist’s short but intense career.

As in the prior episode on Bellini, I invited two curators, Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen, to discuss the paintings on view. Davide is senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum and Keith is the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Davide and Keith go into great detail in their discussion; I encourage you to visit our website to view images of the paintings or look them up elsewhere online while listening.

CHRISTIANSEN: The Borghese Gallery is the collection of one of the great collectors of seventeenth century painting, Scipione Borghese. Antiquities, one of the great patrons of Bernini. And these are all pictures that he personally acquired.

GASPAROTTO: Yes. In fact, the Galleria Borghese has the largest collection of paintings by Caravaggio in the world. Actually, he was one of the first great patrons of Caravaggio. He was one of the few people. He actually acquired one famous altarpiece, which Caravaggio painted for the Saint Peter Basilica, the Madonna Dei Palafrenieri, which was at some point, rejected. And since he was an admirer, an early admirer of Caravaggio, he purchased it for his own private collection. So he was really sort of a talent scout.

CHRISTIANSEN: And he was also such an avid collector that he was one of the people who tried to get Caravaggio back in Rome after Caravaggio had fled Rome after a tennis match with rivals, in which one was killed. He had been among those who were working to get a papal pardon, so that Caravaggio could return. And when Caravaggio dies, en route back to Rome, the first thing on Scipione Borghese’s mind is how to get the pictures that he had ordered from the artist. And he sends an agent back to Naples, to the Colonna household, to find out where the pictures where. So the pictures he has really have a fascinating story.

CUNO: Davide and Keith began by looking at David with the Head of Goliath, which was painted in a somber and more expressive style near the end of Caravaggio’s career, around 1609 to 1610. The painting measures about 49 inches tall by 40 inches wide.

GASPAROTTO: I believe that some scholars, perhaps Maurizio Calvesi, you know, suggested that the David with the Head of Goliath was in some way a picture that Caravaggio executed for Cardinal Scipione Borghese, in a sort of an act of penitence. And—because in the painting, there is this young David with the sword. It’s a single-figure painting. He’s against a black background. There is a curtain on the left upper corner. And so sort of coming out from his tent, probably. And he’s holding the head of Goliath, a terrifying head, which has the features of Caravaggio himself, which is a self-portrait of Caravaggio.

So there is this sort of departure from an established tradition where sometimes the artist portrayed himself as David. But here, Caravaggio portrays himself instead of as David, as Goliath. What do you think about this?

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Yeah. I think it’s absolutely true. And it becomes more interesting when we recognize that the young man holding his head appears in other Caravaggio paintings. And we can almost certainly identify him as Cecco del Caravaggio, who had an association with Caravaggio as model, as probably an assistant, and as his lover. So this is a picture of Caravaggio [as the] victim not only of the conquering hero, David, but as the victim of his love for the young man.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Interesting, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: And you know, the story of Judith and Holofernes, we have also representation where Judith is the lover and Holofernes is the man [GASPAROTTO: He’s the man who is the lover.] who is the victim of her beauty.

GASPAROTTO: Also, we know that in the tradition, in the Christian tradition, David is the symbol of humility which overcomes pride.

CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.

GASPAROTTO: And so in some way, maybe here, Caravaggio’s making a statement that he’s sort of humiliating himself in front of the pope, in some way, or showing that he is repentant then.

CHRISTIANSEN: But you know, the thing that it strikes me in this picture, that always has, is that there’s a melancholy in this picture.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, totally.

CHRISTIANSEN: And the figure of David who looks at Goliath, is clearly looking at him not with a visage of triumph, or of arrogance or of youth audacity, but he’s looking at him with a sense of loss of life, of he does have a victim. And he’s the agent—

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] I think—to me, I think it’s a very moving image, because it—you know, the religious subject becomes something very personal. But at the same time, the entire painting becomes a meditation. Here is the artist meditating in front of death in general. Not only of his own death, of his own mortality, but it’s meditating on human mortality in some way.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, I think it’s worth reminding people that for artists in the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth century, the great stories from the Bible or from Classical mythology became vehicles for expressing human sentiment, relations between humans. Humans in their relationship to nature and for presenting the great emotions. And Caravaggio is certainly the artist for whom painting was a stage for emotions.

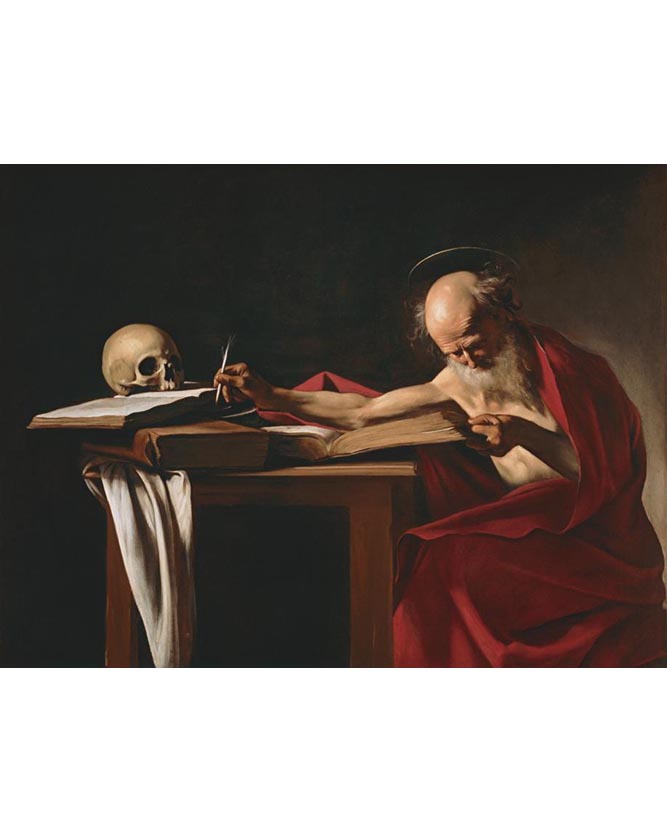

CUNO: Davide and Keith then turned to Saint Jerome, which dates 1605 to 1606, and measures about 44 inches tall by 62 inches wide. The painting portrays the saint as a scholar in the dramatic, spotlit manner for which Caravaggio is best known.

GASPAROTTO: I have to say my favorite pictures among these three is the Saint Jerome. I think the Saint Jerome is a fabulous picture. It’s a particularly moving picture for several reasons.

CHRISTIANSEN: Do you know why you like this?

GASPAROTTO: Uh-huh. Why?

CHRISTIANSEN: Because it’s of a scholar.

GASPAROTTO: [he chuckles] Perhaps.

CHRISTIANSEN: Jerome was the great scholar, the one who translated the Bible into Latin, which was then the common tongue. And he’s shown bent over a book, carefully examining it. He’s holding a quill pen in his right hand, and he’s dipping the quill pen into the ink to write his translation. But sitting before him is another stack of books, on top of which is a skull. And he himself is not dressed. He just has a red robe thrown over his shoulders. He’s an old man, and Caravaggio has focused directly on the bald head where the light hits. So he’s an old man, towards the end of his life, still busy at work in his very simple study. We don’t have any vision of the study. It’s a blank background. But the table is an incredibly simple one.

GASPAROTTO: Simple. Everything is so simple.

CHRISTIANSEN: Everything is simple.

GASPAROTTO: The background is neutral, and there is this concentration, in some way, on these, I would say, three elements. The head of Saint Jerome, the skull, which is sort of contrasting, and then this hand in the middle with the pen.

CHRISTIANSEN: Do you think it says anything about his legacy, which is his writing and his realization that after death, it’s his work as a scholar that will live on? Or is this too self-centered?

GASPAROTTO: Maybe it’s too centered. [they laugh] I don’t know. But the other thing I think it’s important, which is, I think, typical of Caravaggio, especially in this phase, but in his entire painting—the sort of staging.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah.

GASPAROTTO: It seems so natural. The figure, the portrait seems so natural, a portrait of an old man. You know, with the flesh, kind of decaying flesh. But at the same time, the painting is very staged. The stage in the studio, a stage in a neutral space, in a fictive space. So I think Caravaggio makes us aware that this is real, but at the same time, it is a sort of a theater.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah. You remember that Caravaggio was criticized in his own lifetime, because he liked to paint directly from the model. He didn’t like the whole process of Michelangelo, which drew from the model and then it goes through a process of idealization, so that the final figure is an ideal depiction of humanity in general.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Yes. Yes, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: He wanted the specificity of the model itself.

GASPAROTTO: And also he was criticized because he was painting, as Bellori, I think, says, “histories without action.”

CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right. Because if you paint a posed model, you risk losing the quality of movement, of having time introduced into the picture.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: But at the same time, there’s extraordinary artifice in this.

GASPAROTTO: In this, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And if you notice, the light, of course, always from the left, high, raking across the figure, so that you get these marvelous highlights on the forehead, on the nose, on the eye. The shadows of the skull and so forth. But the lit portion is against a dark background.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And the darker portion, which is the red robe in shadow, is against an arbitrarily illuminated background, which he needs to separate the background from the foreground. So there’s artifice involved in this. It looks incredibly naturalistic, in the most general meaning of the term; but in fact, he’s carefully contrived this for a staged effect.

GASPAROTTO: I believe we know that at some point, we have documents that he made a hole in the roof of his room where he was living now, to have this sort of natural light coming up from the roof. And yeah, it’s amazing.

And the other thing that strikes me in this painting is how it opens the entire Baroque season, the entire seventeenth century painting, because of the format, because of the type of composition. It became a model for generations to come, I think.

CHRISTIANSEN: Well, the whole new process of painting, which was to use models to paint from directly; which immediately suggested different rapport with reality and the world of everyday life. But also the focus on pictorial effects, achieved through a very quick brushwork, such as if you looked at that highlight on the forehead, you’ll see one, two, three, four quick little brushstrokes.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: If you look at the eye, you’ll see one quick brushstroke. The eyes are not actually defined. We’re already halfway to Manet in nineteenth century painting.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: So we would not have Velázquez, we would not have Ribera, we would not have any of the great figures that we view as the harbingers of modern painting, of nineteenth century painting, without Caravaggio’s fundamental innovation.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: We have a painting currently hanging at the Metropolitan, in which a Classical story is depicted using a real figure. It’s the story of Midas washing the curse away from—where everything turns to—The Midas touch, everything turns to gold. And it becomes a personal, existential crisis, not a Classical story that’s retold. And this is true of the Jerome. You feel the presence of this figure potentially in the everyday. In the table, there’s no emphasis on it being a table, a Roman table. It’s a table that’s of use in the early seventeenth century.

CUNO: Finally, Davide and Keith looked at Boy with a Basket of Fruit from the beginning of Caravaggio’s career when he was painting realistic genre scenes and still lifes. Painted from 1593 to 1594, the painting measures about 28 inches tall by 26 inches wide.

CHRISTIANSEN: We’ve gone sort of backwards, but the early picture is about somebody from everyday life.

GASPAROTTO: The Boy with a Basket of Fruit. It’s an amazing painting. I have to say, to see it here, not in the very busy gallery of the Galleria Borghese, is really sort of very revelatory. It’s so different from the other more mature, I think, paintings. But at the same time, yes, you feel the continuity of Caravaggio’s interest toward the representation of reality in some way. Even if this is also posed, it’s staged in some way.

CHRISTIANSEN: Absolutely staged. Almost certainly painted for the market. For an open market. A new phenomenon in Western painting that the market is the means through which painters become known. He arrives in Rome, he’s an unknown figure. He has to struggle, he works with various artists. This was actually owned by an artist that he worked with, the Cavaliere d’Arpino, who was a bit older than Caravaggio, just a few years. But who had a huge reputation. And he also had a stock of paintings. And that’s how this picture ends up with Scipione Borghese, who confiscates a group of paintings.

The picture done for the market means that the artist has an opportunity to invent, without attachment to any commission or program imposed on him. So the thing that’s astonishing to me is that he puts in the foreground an extraordinary depiction of a basket of fruit with grapes, peaches, apples, these—I think these are these little pears, aren’t they?

GASPAROTTO: Figs, yes, and sort of pears, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And the leaves, which are quite extraordinary, particularly the one in the foreground, which has a hole in it, eaten, which—a corrupt nature.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: And that’s very important, that he neve wants a perfected nature. He wants nature in its corruption, just as he looks at the David with the head of Goliath not as a triumphant story, as an allegory, but as a real tragedy.

GASPAROTTO: And the basket, too, [CHRISTIANSEN: Ah!] is a very simple basket. It’s not one of the luxury baskets or plates or—we’ve seen some, for example, Dutch or Northern still life, or in Bruegel, [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] which was a kind of a contemporary.

CHRISTIANSEN: And if you think that after Raphael and Michelangelo, there seemed to be a great hierarchy of art, in the arts. And the height of that was the ideal male nude figure. At the very bottom was still life painting, because still life painting was viewed as simply copying from nature.

GASPAROTTO: Copying from nature.

CHRISTIANSEN: So what does Caravaggio do in this early work? He puts the still life in the foreground and the figure reversed. And it’s not an idealized figure. He pulls the shirt down, so that you see this awkward shoulder and collarbone. So that it’s a direct confrontation with the hierarchies of painting that he’s introduced to.

And this is what really got Caravaggio into trouble. And it’s also why he marks a revolution in painting. He would not accept the hierarchy.

GASPAROTTO: One of the few statements that is reported by the sources is that he was saying, you know, that it takes [as] much artistry to do a still life than a figure.

CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.

GASPAROTTO: So I think that’s very important, because it’s totally reversing traditional hierarchies, the hierarchies that were coming from the tradition of the sixteenth century especially.

CHRISTIANSEN: And you know, you look at these grapes, and the marvelous thing about these grapes—and he’s got three different kinds of grapes. I’m a great lover of grapes when I’m in Italy. He doesn’t have my favorite, [Gasparotto laughs] which are the Muscat grapes.

GASPAROTTO: And these are amazing, because there is this sort of dust [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s it!] on them.

CHRISTIANSEN: They have the oxidation on the skin.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Which we associate with them. It’s really an astonishing picture, and leads up to an independent still life that he does for Cardinal Federico—

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Federico Borromeo, which is in the Ambrosiana in Milan, which is one of the first independent still life of European painting. And it leads to an entire new season, even in this case, of the development of European painting. So—

CHRISTIANSEN: So let’s talk a little bit about the boy. Because the boy, once again, there’s marvelous artifice. His head is set against a pale gray background. And below him, at intersecting diagonals, are shadows. So that his head is clearly highlighted against this. And he’s looking directly out at the viewer. His mouth is parted, as though he were speaking.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: But there’s also a seductive element to this picture, and this is one of these elements that has engaged scholars, because all of his pictures invite viewers. And almost seem to solicit viewers, offering fruit for sale.

GASPAROTTO: There is this sort of strong connection. There’s a sort of speaking likeness before Bernini, with his busts, with his portrait busts in marble, created the sort of—the new genre of a portrait which is speaking, which is talking to the viewer, which is directly engaging the viewer. Even in this case, I think there is a the idea that this is obviously a real person and one of Caravaggio’s friends. Probably this is Sicilian painter, Minniti. You know, [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] Mario Minniti. So it’s—even this one is a sort of a portrait of a real person.

CHRISTIANSEN: Now, there’s also in this, in art historical terms, a very interesting confrontation between two opposing traditions. And one of them is the tradition of the area that you’re from, the north, northern painting, where there was already a tradition for a greater amount of naturalism; and the Roman tradition, descending from Raphael and Michelangelo, of idealism.

And Caravaggio has arrived with all the baggage of his northern training and working from life with a sense of naturalistic description. And he confronts a Roman world that is opposed to this. And he simply breaks through.

GASPAROTTO: But to me, it’s always extraordinary how from this starting point, from this half-length figure, from this genre paintings, which, you know, characterize the first phase of his career in Rome, then at some point, suddenly he becomes the most amazing religious painter of his time, and probably one of the most amazing religious painters of all time. His trajectory is incredible.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. That his calling card should be a modest-scaled genre picture. And then he gets commissions for a major altarpiece, and he shifts gears entirely, and transforms the world of painting. The Jerome gives one a real clear sense of what he’s going to do in religious painting that will be earth-shaking.

Already in 1603, word had reached the Netherlands that he had overturned the art world, and that virtually all the foreign artists who were traveling to Rome were becoming followers of Caravaggio and adopting his methods.

CUNO: It was an extraordinary privilege to listen to two passionate and articulate curators talk about paintings they know well and love. Their conversation brought me back to when I first studied these paintings as a student and the excitement that came from looking closely and patiently at works of art. Thanks so much for listening.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

DAVIDE GASPAROTTO: This painting, because of the format, because of the type of composition. It ...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Very much appreciated this lecture!